|

On eBay Now...

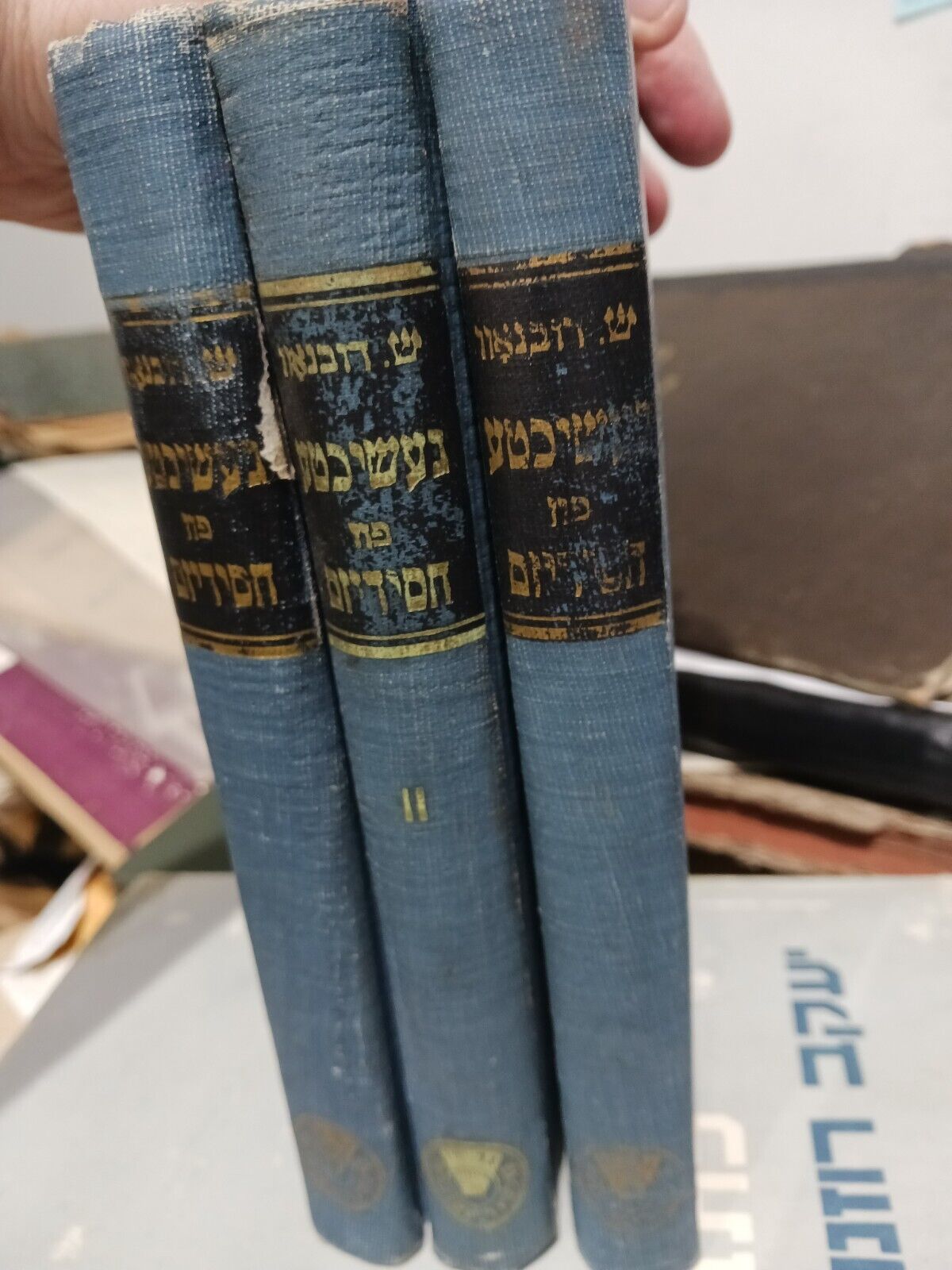

YIDDISH CHASIDUS 3 VOLUMES RARE געשיכטע פון חסידיזם, דובנוב שמעון בוענאס איירעס For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

YIDDISH CHASIDUS 3 VOLUMES RARE געשיכטע פון חסידיזם, דובנוב שמעון בוענאס איירעס:

$1799.00

געשיכטע פון חסידיזם, דובנוב שמעון בוענאס איירעס תשי"ז-תשי"ח (1957 1958) 3 כרכים.Very rare to find a complete set. ..covers all of the Jewish Chassidic groups worldwide 🌐געשיכטע פון חסידיזם : אויפן יסוד פון אריגינעלע מקורים, געדרוקטע און כתב-ידןדובנאוו, שמעוןGeshikhṭe fun Ḥasidizm oyfn yesod fun originele meḳoyrim gedruḳṭe un ksav-yadnDUBNOW, SIMON, 1860-1941============שמעון ברוסית:Семён Маркович Дубнов;ב' בתשריה'תרכ"א,10 בספטמבר1860–8 בדצמבר1941) במזרח אירופה. אבי החילונית, מהוגי האידאולוגיה האוטונומיסטית היהודיתומייסד תנועת הפולקיסטים. ידוע במיוחד בזכות ספרו ההיסטורי המונומנטלי, "דברי ימי עם עולם", שהיווה את הפרשנות החילונית המובהקת הראשונה לתולדות ישראל. כתב ברוסית, חייו[עריכת קוד מקור|עריכה] שמעון דובנוב נולד למאיר יעקב ושיינא דובנוב ביום ב' שלראש השנהה'תרכ"א(1860) הלבנה, אז בתחום המושבשלהאימפריה הרוסית. את ראשית חינוכו קיבל בחדר, אך מילדותו נרתע מלימודי התלמודוהפלפול, ונמשך אל התנ"ךוההשכלה[1]. ב-1874למד בבית הספר היהודי הממשלתי, אך לאחר מכן עבר לבית ספר כללי. לאחר סיום לימודיו התיכוניים ניסה להתקבל לבית המדרש למורים במספר מקומות, אך הוא לא התקבל. בינתיים התעמק בספרותובהגות ההיסטוריתהיהודית והכללית. מ־1880עד 1884[2]עבר להתגורר בסנקט פטרבורגעם אחיו הבכור,זאב דובנוב, שהיה מראשיהביל"ויים.שם הוא החל לכתוב בעיתון היהודי הרוסי "ווסחוד" (ברוסית: זריחה). בשלב זה של חייו הוא נמשך אל בחריפות כנגד היהדות. פרסומיו משכו את תשומת לבם של הקוראים והעיתון, ובשנת1883הפך לעורך המדור לביקרות ספרים בעיתון[1]. דעותיו הריאקציונריותבנוגע ליהדות התבטאו תחילה גם כלפי התנועה הציונית, והוא התנגד לתנועתחיבת ציוןוליישוב ארץ ישראל. ואולם, בהדרגה הוא שינה את דעותיו הקוסמופוליטיות והחל להתמקד יותר בנושא היהודי. "עתה הבנתי, כי דרכי אל האנושיות עובר דווקא באותו החבל הלאומי שבו כבר עבדתי, כי לעבוד לטובת האנושיות עבודה ממשית אפשר רק על ידי עבודה לטובת אחד מחלקיה - ומה גם לטובת העם בעל תרבות עתיקה"[1]השינוי התחולל בו ב-1887, ומאז החל להתעסק בחקרתולדות ישראל. דובנוב עבר בשנת 1890[2]להתגורר באודסהוהתרועע עםמנדלי,אחד כאן גם החל במחקריו בחקר תולדות יהדותמזרח אירופה, מכיוון שהתחום המזרח אירופי של ההיסטוריה היהודית קופח במחקרים הקיימים. בשנת1892פרסם ב"פרדס" בעריכת רבניצקי את הכרוז שלו: "נחפשה ונחקורה", בו הוא קרא אל "הנבונים בעם" לאסוף חומר לתולדות ישראל בפולין וברוסיה. הוא שב ופרסם את קריאתו ב"לוח אחיאסף", ובעקבות כרוזים אלו הוקמה ועדה החומר שנאסף בתחום[1]. ב-1897החל לפרסם בירחון "ווסחוד" את ה"מכתבים על היהדות הישנה והחדשה"; ב-1907 נאספו המכתבים לספר בשם זה[3]. באסופה זו פיתח דובנוב את השקפתו אודות הפזורה הלאומית של היהודים, השקפה שהוותה בסיס להשקפה האוטונומיסטית. במכתבים, שהראשון מהם יצא בזמן הקונגרס הראשון של ההסתדרות הציונית, הוא התפלמס הן עם הציונותוהן עם גישתהבונד. כבר במכתב הראשון שכותרתו "תורת הלאומיות הישראלית" טען שבקהילה היהודית יש שלוש גישות: הגישה הטריטוריאלית - המיוצגת על ידי הציונות, הגישה הסוציאליסטית של הבונד, והגישה - הנכונה ביותר לדעתו - היא הגישה האוטונומיסטית. תחילה החל דובנוב לתרגם את ספר ההיסטוריה הפופולרי שלצבי גרץ, אך לא השלים אותו, ואז פנה לתרגום ספרו ההיסטורי של בראנן-בק, בו החל לפרט את התאוריה האוטונומיסטיתשלו, אותה פיתח בסדרת "מכתבים על היהדות הישנה והחדשה". דובנוב דגל בשלטון אוטונומי בגולה, דוגמתועד ארבע הארצות.אחד העםהתנגד לתאוריה של דובנוב, והביע את דעותיו השונות במאמריו: "שלוש מדרגות", ו"שלילת הגלות"[4]. ב-1902 החל את מפעלו ההיסטוריוגרפיהגדול בכתיבת תולדות האומה בכל מרכזיה, מזרח ומערב, ובכל זמניה - מימי קדם ועד יום הכתיבה: "דברי ימי עם עולם"; הוא התעסק במפעל זה עד סוף ימיו. הספר נכתב ברוסית, השפה בה פרסם את רוב כתביו, והסתיים בתחילת שנות העשרים; לאחר מכן באו התרגומים לגרמניתולעברית וההשלמות. ב-1912עמד עם ד"רי"ל קצנלסוןבראש המפעל האנציקלופדי "ייברסקיה אנציקלופדיה" ("האנציקלופדיה היהודית", בשפה הרוסית). אנציקלופדיה זו התבססה עלהאנציקלופדיה היהודית, אך באה להשלים את החסר בה, והדגישה גם את חשיבותן שלקהילות ישראל במזרח אירופה. ב-1917 הביע דאגה להשלכות המהפכה הרוסית על עתיד היהודים, אך שאב עידוד מפעולתם הציבורית הלאומית של אישים כמוישראל זנגוויל.[5] ב-1922 עזב דובנוב את רוסיה – מאוכזב מכל ההגבלות וההפרעות שנגרמו לו בעבודתו המדעית - והגיע לקובנהבירתליטא. כאן הוצעה לו ראשות הקתדרהלדברי ימי ישראל באוניברסיטה הליטאית, אולם הפרופסורים הנוצרים לא ראו את מינויו בעין יפה, ולכן עקר לברלין, וישב שם כ-11 שנה. שם השלים את מפעלו החשוב כהיסטוריון,חיבורו המקיףבן 11 הכרכים, "דברי ימי עם עולם" (תורגם לעברית ב-1923–1939). עםעליית הנאצים לשלטון בגרמניהעבר לגור בלטביה. לאחר פרוץמלחמת העולם השנייההפצירו בו מכריו לעלות לארץ ישראל, אולם בתחילת שנת1940הוא סירב והעדיף להישאר בלטביה עם ידידיו. בראשית שנת1941ניסתהרוזה גינוסרלהשיג עבורוסרטיפיקט, לאחר שהביע הסכמה להגר מלטביה. היא פנתה למנחם אוסישקין, אשר אמר שיש להעדיף לתת את מעט הסרטיפיקטים לפעילים ציוניים. לעומתו,יהודה לייב מאגנספעל להשיג עבור דובנוב סרטיפיקט, אולם השעה נתאחרה ודובנוב לא הספיק לצאת לפני שהנאצים כבשו את לטביה[6]. כאשר כבשו הנאצים אתריגהנכלא דובנוב עם שאר יהודי העיר בגטו ריגה. ב-8 בדצמבר1941 הובל עם אלפי יהודים למותם בגיא ההריגה ביער רומבולה, שם נטבחו אלפי יהודים. מחמת מחלתו נחסך ממנו המסע המפרך – שוטר לטבי ירה בו והרגו. טענה אחרת היא שנרצח בדרך על ידי אחד מתלמידיו לשעבר, שהיה קציןגסטפו[7]. ================== Simon Dubnow(alternatively spelledDubnov;Yiddish:שמעון דובנאָװ,romanized:Shimen Dubnov; Russian:Семён Ма́ркович Ду́бнов,romanized:Semyon Markovich 10 September 1860– 8 December 1941) was aJewish-Russianhistorian, writer and activist. Life and career[edit]In 1860,[1]: 18 Simon Dubnow was bornShimon Meyerovich Dubnow(Шимон Меерович Дубнов) to a large poor family in theBelarusiantown ofMstsislaw(Mogilev Region). A nativeYiddishspeaker, he received a traditional Jewish education in ahederand ayeshiva, whereHebrewwas regularly spoken. Later Dubnow entered into akazyonnoye yevreyskoe uchilishche(state Jewish school) where he learnedRussian. In the midst of his education, theMay Lawseliminated these Jewish institutions, and Dubnow was unable to graduate;[citation needed]Dubnow persevered, independently pursuing his interests inhistory,philosophy, andlinguistics. He was particularly fascinated byHeinrich Graetzand theWissenschaft des Judentumsmovement. In 1880 Dubnow used forged documents to move toSt Petersburg, officially off-limits to Jews. Jews were generally restricted to small towns in thePale of Settlement, unless they had been discharged from the military, were employed as doctors or dentists, or could prove they were 'cantonists', university graduates or merchants belonging to the 1st guild. Here he married Ida Friedlin.[2] Soon after moving to St. Petersburg Dubnow's publications appeared in the press, including the leading Russian–Jewish magazineVoskhod. In 1890, the Jewish population was expelled from the capital city, and Dubnow too was forced to leave. He settled inOdesaand continued to publish studies of Jewish life and history, coming to be regarded as an authority in these areas. Throughout his active participation in the contemporary social and political life of theRussian Empire, Dubnow called for modernizing Jewish education, organizing Jewish self-defense againstpogroms, and demanding equal rights for Russian Jews, including the right to vote. Living inVilna,Lithuania, during the early months of1905 Russian Revolution, he became active in organizing a Jewish political response to opportunities arising from the new civil rights which were being promised. In this effort he worked with a variety of Jewish opinion, e.g., those favouringdiaspora autonomy,Zionism,socialism, andassimilation.[3][4] In 1906 he was allowed back into St Petersburg, where he founded and directed the Jewish Literature and Historical-Ethnographic Society and edited theJewish Encyclopedia. In the same year, he founded theFolkspartei(Jewish People's Party) with Israel Efrojkin, which successfully worked for the election ofMPsand municipal councilors in interwarLithuaniaandPoland. After 1917 Dubnow became a professor of Jewish history atPetrograd University. He welcomed the firstFebruary Revolutionof 1917 in Russia, regarding it, according to scholarRobert van Voren, as having "brought the long-anticipatedliberationof the Jewish people", although he "felt uneasy about the increasing profile ofLenin".[5]Dubnow did not consider suchBolsheviksasTrotsky(Bronstein) to be Jewish, stating: "They appear under Russian pseudonyms because they are ashamed of their Jewish origins (Trotsky,Zinoviev, others). But it would be better to say that their Jewish names are pseudonyms; they are not rooted in our people."[6][7][8] In 1922 Dubnow emigrated toKaunas,Lithuania, and later toBerlin. Hismagnum opuswas the ten-volumeWorld History of the Jewish people, first published inGermantranslation in 1925–1929. Of its significance, historianKoppel Pinsonwrites: With this work Dubnow took over the mantle of Jewish national historian fromGraetz. Dubnow'sWeltgeschichtemay in truth be called the first secular and purely scholarly synthesis of the entire course ofJewish history, free from dogmatic and theological trappings, balanced in its evaluation of the various epochs and regional groupings of Jewish historical development, fully cognizant of social and economic currents and influences...[9] During 1927 Dubnow initiated a search in Poland forpinkeysim(record books kept byKehillotand other local Jewish groups) on behalf of theYidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut(YIVO, Jewish Scientific Institute), while he was Chairman of its Historical Section. This spadework for the historian netted several hundred writings; onepinkesdated to 1601, that of the Kehillah ofOpatów.[10] In August 1933, afterHitlercame to power, Dubnow moved toRiga,Latvia. He chose Latvia in part for its government's support for Jewish self-reliance and the vigorous Jewish community in the small country. There existed a Jewish theater, various Jewish newspapers, and a network of Yiddish-language schools.[1]: 25 There his wife died, yet he continued his activities, writing his autobiographyBook of My Life,[11]and participating in YIVO, the Institute for Jewish Research.[1]: 26 On the initiative of a Latvian Jewish refugee activist in Stockholm and with help from the local Jewish community in Sweden, Dubnow was granted a visa to Sweden in the summer of 1940 but for unknown reasons he never used it.[12]Then in July 1941Nazitroops occupied Riga. Dubnow was evicted, losing his entire library. With thousands of Jews, he was transferred to theRiga ghetto. According to the few remaining survivors, Dubnow repeated to ghetto inhabitants:Yidn, shraybt un farshraybt(Yiddish:Jews", write and record"). He was among thousands of Jews to be rounded up there for theRumbula massacre. Too sick to travel to the forest, he was murdered in the city on 8 December 1941. Several friends then buried Simon Dubnow in the old cemetery of the Riga ghetto.[11] Political ideals[edit]Dubnow was ambivalent towardZionism, which he felt was an opiate for the spiritually feeble.[13]Despite being sympathetic to the movement's ideas, he believed its ultimate goal, the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine achieved with international support and substantial Jewish immigration, to be politically, socially, and economically impossible, calling it "a beautiful messianic dream".[14]In 1898, he projected that by the year 2000, there would only be about 500,000 Jews living in Palestine.[15]Dubnow thought Zionism just another sort of messianism, and he thought the possibility of persuading the Jews of Europe to move to Palestine and establish a state fantastical. Beyond improbability, he worried that this impulse would drain energy away from the task of creating an autonomous Jewish center in the diaspora.[1]: 21 Much stronger than his skepticism towards Zionism, Dubnow rejectedassimilation.[1]: 20 He believed that the future survival of the Jews as a nation depended on their spiritual and cultural strength, where they resided dispersed in thediaspora. Dubnow wrote: "Jewish history [inspires] the conviction that Jewry at all times, even in the period of political independence, was pre-eminently a spiritual nation,"[16][17]and he called the push for assimilation "national suicide".[1]: 20 His formulated ideology became known asJewish Autonomism,[18][19]once widely popular in eastern Europe, being adopted in its various derivations by Jewish political parties such as theBundand hisFolkspartei.Autonomisminvolved a form of self-rule in the Jewish diaspora, which Dubnow called "the Jewish world-nation". TheTreaty of Versailles(1919) adopted a version of it in theminority provisions of treatiessigned with new east European states. Yet in early 20th-century Europe, many political currents began to trend against polities that accommodated a multiethnic pluralism, as grim monolithic nationalism or ideology emerged as centralizing principles. After theHolocaust, and the founding ofIsrael, for a while discussion of Autonomism seemed absent fromJewish politics.[20] Regional history[edit]Dubnow's political thought perhaps can better be understood in light ofhistorical Jewish communal life in Eastern Europe. It flourished during the early period of thePolish–Lithuanian Commonwealth(1569–1795), when it surpassed the Ottoman Empire and western Europe as a center of Judaism.[21][22]Dubnow here describes theautonomoussocial-economic and religious organization developed by the Jewish people under the Commonwealth government: Constituting an historical nationality, with an inner life of its own, the Jews were segregated by the Government as a separateestate, an independent social body. ... They formed an entirely independent class of citizens, and as such were in need of independent agencies of self-government andjurisdiction. The Jewish community constituted not only a national and cultural, but also a civil, entity. It formed a Jewish city within a Christian city, with its separate forms of life, its own religious, administrative, judicial, and charitable institutions. The Government of a country with sharply divided estates could not but legalize the autonomy of the JewishKahal." The Jews also did not speakPolish, but ratherYiddish, an Hebraicized German. "The sphere of the Kahal's activity was very large." "The capstone of this Kahal organization were the so-calledWaads, the conferences or assemblies of rabbis and Kahal leaders. [They became] the highest court of appeal." Their activity "passed, by gradual expansion, from thejudicial sphereinto that of administration and legislation.[23] Each provincial council orWaad(Hebrewvaad: committee) eventually joined with others to form a central governing body which began to meet regularly. Its name became "ultimately fixed as theCouncil of the Four Lands(Waad Arba Aratzoth)." These four lands andVolhynia(OstrohandKremenets); the fifth landLithuania(BrestandGrodno) withdrew to form its own highWaad. The 'Council of the Four Lands' consisted of the six "leading rabbis of Poland" and a delegate from the principalKahalemselected by their elders, in all about thirty members. "As a rule, the Council assembled inLublinin early spring, betweenPurimandPassover, and inYaroslav(Galicia) at the end of summer, beforehigh holidays."[24] The Council orWadd Arba Aratzoth"reminded one of theSanhedrin, which in ancient days assembled... in thetemple. They dispensed justice to all the Jews of the Polish realm, issued preventive measures and obligatory enactments (takkanoth), and imposed penalties as they saw fit. All difficult cases were brought before their court. To facilitate matters [the delegates appointed] 'provincial judges' (dayyane medinoth) to settle disputes concerning property, while they themselves [in plenary session] examined criminal cases, matters pertaining tohazaka(priority of possession) and other difficult matters of law."[25]"The Council of the Four Lands was the guardian of Jewish civil interests in Poland. It sent itsshtadlansto the residential city ofWarsawand other meeting-places of thePolish Dietsfor the purpose of securing from thekingand hisdignitariesthe ratification of the ancient Jewish privileges.[26]... But the main energy of theWaadwas directed toward the regulation of the inner life of the Jews. The statute of 1607, framed [by] the Rabbi of Lublin, is typical of this solicitude. [Its rules were] prescribed for the purpose of fostering piety and commercial integrity among the Jewish people.[27] This firmly-knit organization of communal self-government could not but foster among theJews of Polanda spirit of discipline and obedience to the law. It had an educational effect on the Jewish populace, which was left by the Government to itself, and had no share in the common life of the country. It provided the stateless nation with a substitute for national and political self-expression, keeping public spirit and civic virtue alive in it, and upholding and unfolding its genuine culture.[28][29] Yet then the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth suffered grave problems of institutional imbalance.[30][31]Eventually, the Commonwealth was removed from the map of Europe by successivepartitionsperpetrated by her three neighboring states, each an autocracy, the third and extinguishing partition coming in 1795.[32]Following theCongress of Vienna(1815) the Russian Empire uneasily governed most of these Polish and Lithuanian lands, including the large Jewish populations long dwelling there.[33][34][35]TheRussian Empirefirst restricted Jewish residence to their pre-existingPale of Settlement, and later began to further confine Jewish liberties and curtail their self-government.[36]Not only were their rights attacked, but several of the Tzars allowed the imperial government to propagate and to instigate a series of murderouspogromsagainst the Jewish people of the realm.[37] In the cruel atmosphere of this ongoing political crisis in the region, Simon Dubnow wrote his celebrated histories and played an active rôle in Jewish affairs. He supported the broad movements for change in the Russian Empire; yet in the main he sought to restore and to continue the Jewishautonomy, described above at its zenith under the old Commonwealth, into the 20th century.[38] During his life various large and tragic events were to impact the region, which can be considered as the most horrific of places during the first half of the 20th century. Among these events, ranging from a few positive to news headlines to crimes against humanity, were: thepogroms, the co-opted1905 Russian Revolution, the founding of theFolkspartei, theFirst World War, theFebruary Revolutionfollowed by theOctober Bolshevik,[39]theBalfour Declaration, theTreaty of Brest-Litovsk, theVersailles Treaty, thePolish–Soviet War, theWeimar inflation, the U.S.A.Immigration Act of 1924, exile ofLeon TrotskybyJoseph Stalin, the SovietGulag, theGreat Depression,collectivizationof theUkraine, theNazi regime, theNuremberg racial laws, Stalin'sGreat Purge,Kristallnacht, the1939 White Paper, theNazi–Soviet Pact, theSecond World War, theSoviet-Nazi War, and theShoah. The catastrophe of the genocide claimed the life of the aged historian.[40] National values[edit]Spiritual values were highly esteemed by Dubnow, who viewed the Jewish people as leaders in their advancement. In hisWeltgeschichtehe discusses the ancient rivalry betweenSadduceeandPharisee, as a contest between the ideal of apolitical nationversus aspiritual nation. He favored the latter, and mounted a critique of the warlike policies ofAlexander Jannaeus(r. 103-76 BCE), a king of the Jewish Hasmonean dynasty (167-63 BCE), which was founded by theMaccabees: This was not the kind of state dreamed of by their predecessors, thehasidim, when the independence of Judea was attained and when the star of theHasmoneansfirst began to gleam. Had Judeabattled against the Syrian yoke, sacrificed for a quarter of a century its material goods and the blood of its best sons, only in order to become, after attaining independence, a 'despotism' or warrior state after the fashion of its pagan neighbors? The Pharisees believed that the Jewish nation was created for something better; that in its political life it was not to strive for the ideal of brute force but rather for the lofty ideal of inner social and spiritual progress.[41] Not only is there the issue of inner purpose and drive of the communal life of a nation, but also of the ethics of nationalism, relations between nations. Dubnow writes: "There is absolutely no doubt that Jewishnationalismin its very essence has nothing in common with any tendency toward violence." Because of thediasporaexperience, "as a Jew, I utter the word 'national' with pride and conviction, because I know my people... is not able to aspire anywhere to primacy and dominance. My nationalism can be only a pure form...." The prophets "called Israel a 'light to the nations' [and taught] the spiritual mission of the people of Israel... to bring other peoples, that is, all 'mankind,' to spiritual perfection." Thus, the nation inspired by Judaism, "the descendants of theProphets," will promote and inspire thesocial ethicsof humanity, and will come to harmonize with its realization: "the equal worth of all nations in the family of mankind." The "Jewish national idea, which can never become aggressive and warlike" will raise aloft its flag, which symbolizes the joining of the prophetic vision of "truth andjusticewith the noble dream of the unity of mankind."[42] Scholar Baruch Kimmerling describes Dubnow as having "fused nationalism, internationalism, and secular Jewishness into a non-Zionist, non–territorially dependent cultural nationalism."[43] Jewish History[edit]Earlier in a long and well-regarded essay, Dubnow wrote about the "two halves" ofJewish history. The first "seems to be but slightly different from the history of other nations." But if we "pierce to its depths" we find aspiritual people. "The national development is based upon an all-pervasive religious tradition... embracing a luminous theory of life and an explicit code of morality and social converse." Their history reveals that the Jewish people "has been called to guide the other nations toward sublime moral and religious principles, and to officiate for them, the laity as it were, in the capacity of priests." "TheProphetswere the real and appointed executors of the holy command enjoining the 'conversion' of all Jews into 'a kingdom of priests and a holy nation'." After the close of theTanakhera in Israel, this first half of their history, the "strength and fertility" of the Jews as a spiritual nation "reached a culminating point".[44][45] Yet then "the providence of history" changed everything and scattered them "to all ends of the earth". "State, territory, army, the external attributes of national power" became a "superfluous luxury" for the Jews, a hardy and persevering people. Already in the Biblical times, their "character had been sufficiently tempered", they had learned how to "bear the bitterest of hardships" and were "equipped with an inexhaustible store of energy", thus they could survive, "live for centuries, yea, for thousands of years" under challenging conditions in ethnic enclaves mostly in Southwest Asia and later throughout Europe, during their post-Biblical "second half".[46] "Uprooted from its political soil, national life displayed itself [in the] intellectual fields exclusively. 'To think and to suffer' became the watchword of the Jewish people." They brought their "extraordinary mental energy" to the task. "The spiritual discipline of the school came to mean for the Jew what military discipline is for other nations." Dubnow notes that the Jewish people without an army live as if in a future world where nations no longer rise up against each other in war. Hence, for the Jews, their history has become "spiritual strivings" and cultural contributions. "If the inner life and social and intellectual development of a people form the kernel of history, and politics and occasional wars are but its husk, then certainly the history of theJewish Diasporais all kernel."[47] "In spite of the noteworthy features that raise Jewish history above the level of the ordinary and assign it a peculiar place, it is nevertheless not isolated, not severed from the history of mankind." These "pilgrim people scattered in all the countries" are "most intimately interwoven with world-affairs". On the negative, when "the powers of darkness and fanaticism held sway" the Jews were subject to "persecutions, infringement of the liberty of conscience, inquisitions, violence of every sort." Yet when "enlightenment and humanity" prevailed in the neighborhood, the Jews were to benefit by "the intellectual and cultural stimulus proceeding from the peoples with whom they entered into close relations." Across the centuries in our history, such tides seem to ebb and flow.[48] On its side, Jewry made its personality felt among the nations by its independent, intellectual activity, its theory of life, its literature, by the very fact indeed, of its ideal staunchness and tenacity, its peculiar historical physiognomy. From this reciprocal relation issued a great cycle of historical events and spiritual currents, making the past of the Jewish people an organic constituent of the past of all that portion of mankind which has contributed to the treasury of human thought.[49] Dubnow states that the Jewish people in the firstBiblicalhalf of its history "finally attained to so high a degree of spiritual perfection and fertility that the creation of a new religious theory of life, which eventually gained universal supremacy, neither exhausted its resources nor ended its activity." In its second "lackland" half the Jews were "a people accepting misery and hardship with stoic calm, combining the characteristics of the thinker with those of the sufferer, and eking out existence under conditions which no other nation has found adequate." For this people "the epithet 'peculiar' has been conceded" and Jewish history "presents a phenomenon of undeniable uniqueness."[50] Philosophy[edit]In a short article, Dubnow presented a memorable portrait of historical depth, and its presence in contemporary life: Every generation in Israel carries within itself the remnants of worlds created and destroyed during the course of the previous history of the Jewish people. The generation, in turn, builds and destroys worlds in its form and image, but in the long run continues to weave the thread that binds all the links of the nation into the chain of generations. ... Thus each generation in Israel is more the product of history than it is its creator. ... We, the people of Israel living today, continue the long thread that stretches from the days ofHammurabiandAbrahamto the modern period. ... We see further that during the course of thousands of years the nations of the world have borrowed from our spiritual storehouse and added to their own without depleting the source. ... The Jewish people goes its own way, attracting and repelling, beating out for itself a unique path among the routes of the nations of the world... .[51] Another writer of Jewish history although from a younger generation,Lucy Dawidowicz, summarizes the personal evolution and resultingweltanschauungof Simon Dubnow: Early in his intellectual life, Dubnow turned to history and in the study and writing of Jewish history he found the surrogate forJudaism, the modern means by which he could identify as a Jew, which would give him inner satisfaction and keep him part of the Jewish community. ... Even in his pioneering studies ofhasidism, Dubnow's rationalism shines through. ... Yet despite his rationalism, despite his modernity, Dubnow believed in a mystic force--the Jewish will to live.[52] Dubnow himself adumbrates his own philosophical and religious understanding: "I amagnosticin religion and in philosophy.... I myself have lost faith in personalimmortality, yet history teaches me that there is a collective immortality and that the Jewish people can be considered as relatively eternal for its history coincides with the full span of world history."[53]Pinson writes "Dubnow with his profound historical approach, weaves into his automomist theories all the strands of Jewish past, present and future."[54] Dubnow Institute in Leipzig[edit]In honor of Simon Dubnow and as a center for undertaking research on Jewish culture, in 1995, the Leibniz Institute for Jewish History and Culture – Simon Dubnow was founded.[55]It is an interdisciplinary institute for the research of Jewish lived experience in Central and Eastern Europe from the Early Modern Period to the present day. The Dubnow Institute is dedicated to the secular tradition of its namesake. At the Dubnow Institute, Jewish history is always regarded in the context of its non-Jewish environs and as a seismograph of general historical developments. The institute is contributing courses to several degree programs of Leipzig University and offers a Ph.D. research scheme.

YIDDISH CHASIDUS 3 VOLUMES RARE געשיכטע פון חסידיזם, דובנוב שמעון בוענאס איירעס $1799.00

YIDDISH BOOK=פשיסכע און קאצק ספר באידיש על חסידות פשיסכע וחסידות קאצק KOTZK MINT $299.00

Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular and the New Land $14.56

Yiddishkeit: Jewish Vernacular and the New Land $13.93

|