|

On eBay Now...

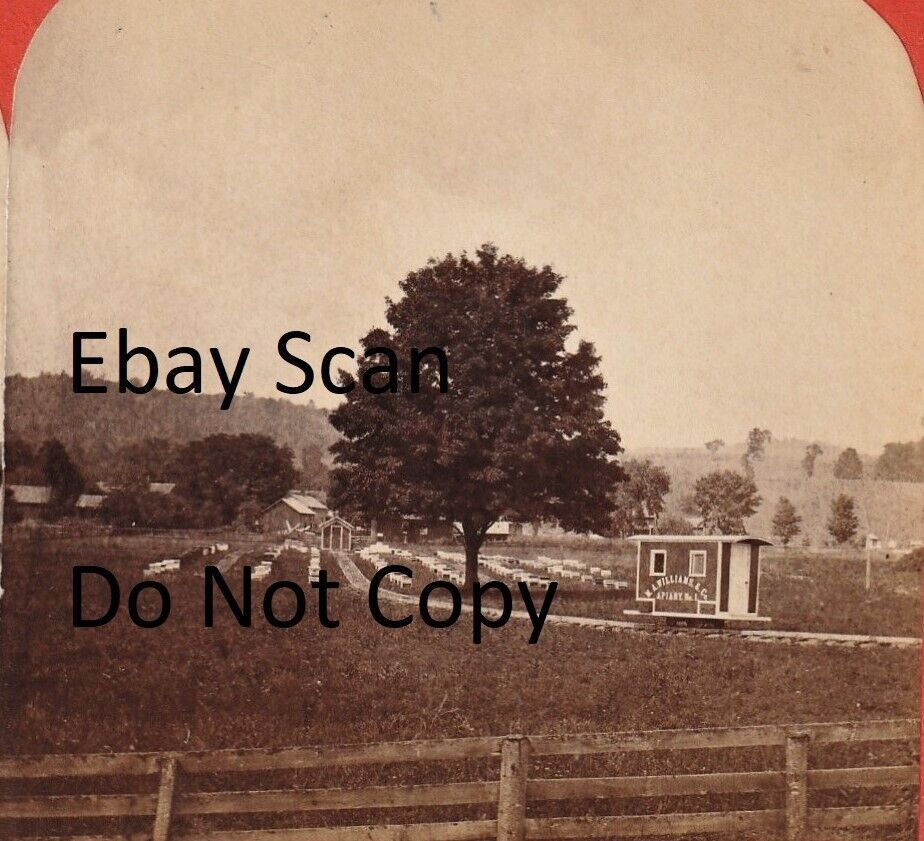

Railroad Apiary Car & Track - Berkshire NY 1860s Bees xRARE Stereoview Photo - For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

Railroad Apiary Car & Track - Berkshire NY 1860s Bees xRARE Stereoview Photo -:

$595.00

Very RARE old Stereoview Photograph

Exceptionally RARE image

M.A. Williams Railroad Apiary Car & Track

Early Beekeeping / honey railroad invention

Berkshire, New York

ca 1860sFor offer, a nice old stereoptican view card photo! Fresh from a prominent estate in Upstate, NY.Vintage, Old, Original - NOTa Reproduction - Guaranteed !! An article about this idea / invention appeared in the American Bee Journal in 1861, where Williams explains his idea of using this little RR car to extract honey for easier transport. 140 colonies at this apiary. Side of car reads M.A. Williams, Apiary no. 1. One of a kind / unique image. The \"do not copy\" added digitally to prevent people from copying image. In good to very good condition. As shown in photos -Please seephotos. If you collect19thcentury Americana history, sv photography, American history, etc.this is a treasureyou will not see again!Add this to your image orpaper/ ephemera collection. Combine shipping on multiple purchases. 2824

An apiary (also known as a bee yard) is a location where beehives of honey bees are kept. Apiaries come in many sizes and can be rural or urban depending on the honey production operation. Furthermore, an apiary may refer to a hobbyist\'s hives or those used for commercial or educational usage. It can also be a wall-less, roofed structure, similar to a gazebo which houses hives, or an enclosed structure with an opening that directs the flight path of the also: Beekeeping § History Apiaries have been found in ancient Egypt from prior to 2422 BCE where hives were constructed from moulded mud.[1] Throughout history apiaries and bees have been kept for honey and pollination purposes all across the globe. Due to the definition of apiary as a location where hives are kept its history can be traced as far back as that of beekeeping known usage of the word \"apiary\" was in 1654.[2] The base of the word comes from the Latin word \"apis\" meaning \"bee\", leading to \"apiarium\" or \"beehouse\" and eventually may rarely be referred to as \"apiarists\" or \"ones who tend apiaries.\"[3] By definition an apiary is a location where beehives are kept; although the word is also used to refer to any location where bees swarm and molt. The word apiarist typically refers to a beekeeper who focuses on just one species of bee. The word apiarist first appeared in print in a 1940 book written by Walter de Gruyter. It was a phrase coined by apiarists to describe how apiaries were may vary by location and according to the needs of the individual operation. Typically, apiaries are composed of several individual hives. For more information on specific hive structures see the beekeeping and beehive articles. In the case of urban beekeeping, hives are often located on high ground, which requires less space than hives located at lesser altitudes.[4] To direct the bees\' path of flight in populous urban areas, beekeepers often construct tall fences which force the bees to fly higher and widen their search for food [4] or place the hives in an enclosed apiary with an opening that directs bees’ flight path up (Bienenhaus) in Upper Bavaria, Germany Apiaries are usually situated on high ground in order to avoid moisture collection, though in proximity to a consistent water source—whether natural or man-made—to ensure the bees\' access.[5] Additionally, ample nectar supplies for the bees as well as relatively large amounts of sun are considered.[5] They are often situated close to orchards, farms, and public gardens, which require frequent pollination to develop a positive response loop between the bees and their food sources. This also economizes on the bees\' pollination and the plants\' supply of nectar.[6]

An apiary may have hive management objectives other than honey production, including queen rearing and mating. In the northern hemisphere, east and south facing locations with full morning sun are preferred. In hot climates, shade is needed and may have to be artificially provided if trees are not present. Other factors include air and water drainage and accessibility by truck, distance from phobic people, and protection from vandalism.

In the USA there are beekeepers—from hobbyists to commercial—in every state. The most lucrative areas for American honey production are Florida, Texas, California, and the Upper Midwest.[7] For paid pollination, the main areas are California, the Pacific Northwest, the Great Lakes States, and the Northeast.[7] Rules and regulations by local ordinances and zoning laws also affect apiaries.[8]

In recent years US honey production has dropped and the U.S. imports 16% of the world\'s honey.[9] Internationally, the largest honey producing exporters are China, Germany, and Mexico.[9] As in the United States the location of apiaries varies internationally depending on available resources and the operational need. For more information on nation-specific beekeeping see their respective articles, such as the Beekeeping in Nepal in Bashkortostan, Russia Apiary size refers not only to the spatial size of the apiary, but also to the number of bee families and bees by weight.[10] With ample space there is no limit to the number of hives or bee families which can be housed in an apiary. The larger the number of hives held in an apiary the higher the yield of honey relative to resources, often resulting in apiaries growing with time and experience.[10] Additionally a higher number of hives within an apiary can increase the quality of the honey produced.[10] Depending on the nectar and pollen sources in a given area, the maximum number of hives that can be placed in one apiary can vary. If too many hives are placed into an apiary, the hives compete with each other for scarce resources. This can lead to lower honey, flower pollen and bee bread yields, as well as higher transmission of disease and robbing.[11]

The size of an apiary is determined by not only the resources available but also by the variety of honey being cultivated, with more complex types generally cultivated in smaller productions. For more specific details on varieties see the classification portion of the honey article. The purpose of the apiary also affects size: apiaries are kept by commercial and local honey producers, as well as by universities, research facilities, and local organizations. Many such organizations provide community programming and educational opportunities. This results in varying sizes of apiaries depending on usage maximum size of a permanent apiary or bee yard may depend on the type of bee as well. Some honey bee species fly farther than others. A circle around an apiary with a three-mile (5 km) foraging radius covers 28 square miles (73 km2). A good rule of thumb is to have no more than 25–35 hives in a permanent apiary, although migrating beekeepers may temporarily place one hundred hives into a location with a good nectar flow.

Disease and decline Apiaries may decline due to a scarcity of resources which can lead to robbing of nearby hives. This is especially an issue in urban areas where there may be a limited amount of resources for bees and a large number of hives may be affected.[13]

Apiaries may suffer from a wide variety of diseases and infestations.[14] Throughout history apiaries and bees have been kept for honey and pollination purposes all across the globe. Due to the definition of apiary as a location where hives are kept its history can be traced as far back as that of beekeeping itself. In recent years Colony Collapse Disorder due to pesticide resistant mites have ravaged bee populations.[15] Beyond mites there are a wide variety of diseases which may affect the hives and lead to the decline or collapse of a colony. For this reason many beekeepers choose to keep apiaries of limited size to avoid mass infection or infestation. For more information on diseases which affect bee populations see the list of diseases of the honey bee.

See (or apiculture) is the maintenance of bee colonies, commonly in man-made hives, by humans. Most such bees are honey bees in the genus Apis, but other honey-producing bees such as Melipona stingless bees are also kept. A beekeeper (or apiarist) keeps bees in order to collect their honey and other products that the hive produces, such as beeswax, propolis, flower pollen, bee pollen, and royal jelly, as well as to pollinate crops or to produce bees for sale to other beekeepers. A location where bees are kept is called an apiary or \"bee yard\".

The keeping of bees dates back to 10,000 years ago, and has been traditionally done for honey. Georgia is the \"cradle of beekeeping\" and the oldest honey ever found comes from the country. The 5,500-year-old find was unearthed from the grave of a noblewoman during archaeological excavations in 2003 near the Borjomi town.[1] The ceramic jars contained several types of honey, including linden and flower honey. The domestication of bees can be seen in Egyptian art from around 4,500 years ago. There is also evidence of beekeeping in ancient China, Greece, and Maya.

In the modern era, beekeeping is more often used for crop pollination and other products, such as wax and propolis. The largest beekeeping operations are agricultural businesses that are operated for profit, though many people have small beekeeping operations that they run as a hobby. As beekeeping technology has advanced, beekeeping has become more accessible, and urban beekeeping was described as a growing trend as of 2010. Some studies have found that \"city bees\" are actually healthier than \"rural bees\" because there are fewer pesticides and greater seeker depicted on 8,000-year-old cave painting near Valencia, Spain[3] Further information: Western honey bee § Domestication Early history At some point in history at least 10,000 years ago, humans began to attempt to maintain colonies of wild bees in artificial hives made from hollow logs, wooden boxes, pottery vessels, or woven straw baskets (known as skeps). Depictions of humans collecting honey from wild bees date to 10,000 years ago.[4] Beekeeping in pottery vessels began about 9,000 years ago in North Africa.[5] Traces of beeswax are found in potsherds throughout the Middle East beginning about 7000 BCE.[5] Domestication of bees is shown in Egyptian art from around 4,500 years ago.[6] Simple hives and smoke were used and honey was stored in jars, some of which were found in the tombs of pharaohs such as Tutankhamun. It was not until the 18th century that European understanding of the colonies and biology of bees allowed the construction of the movable comb hive so that honey could be harvested without destroying the entire colony.

Honeybees were kept in Egypt from antiquity.[7] On the walls of the sun temple of Nyuserre Ini from the Fifth Dynasty, before 2422 BCE, workers are depicted blowing smoke into hives as they are removing honeycombs.[8] Inscriptions detailing the production of honey are found on the tomb of Pabasa from the Twenty-sixth Dynasty (c. 650 BCE), depicting pouring honey in jars and cylindrical hives.[9]

An inscription records the introduction of honey bees into the land of Suhum in Mesopotamia, where they were previously unknown: I am Shamash-resh-ușur, the governor of Suhu and the land of Mari. Bees that collect honey, which none of my ancestors had ever seen or brought into the land of Suhu, I brought down from the mountain of the men of Habha, and made them settle in the orchards of the town \'Gabbari-built-it\'. They collect honey and wax, and I know how to melt the honey and wax – and the gardeners know too. Whoever comes in the future, may he ask the old men of the town, (who will say) thus: \"They are the buildings of Shamash-resh-ușur, the governor of Suhu, who introduced honey bees into the land of text from stele, (Dalley, 2002)[10] The oldest archaeological finds directly relating to beekeeping have been discovered at Rehov, a Bronze and Iron Age archaeological site in the Jordan Valley, Israel.[11] Thirty intact hives, made of straw and unbaked clay, were discovered by archaeologist Amihai Mazar in the ruins of the city, dating from about 900 BCE. The hives were found in orderly rows, three high, in a manner that could have accommodated around 100 hives, held more than 1 million bees and had a potential annual yield of 500 kilograms of honey and 70 kilograms of beeswax, according to Mazar, and are evidence that an advanced honey industry existed in ancient Israel 3,000 years Beekeepers, 1568, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder In ancient Greece (Crete and Mycenae), there existed a system of high-status apiculture, as can be concluded from the finds of hives, smoking pots, honey extractors and other beekeeping paraphernalia in Knossos. Beekeeping was considered a highly valued industry controlled by beekeeping overseers—owners of gold rings depicting apiculture scenes rather than religious ones as they have been reinterpreted recently, contra Sir Arthur Evans.[15] Aspects of the lives of bees and beekeeping are discussed at length by Aristotle. Beekeeping was also documented by the Roman writers Virgil, Gaius Julius Hyginus, Varro, and has also been practiced in ancient China since antiquity. In a book written by Fan Li (or Tao Zhu Gong) during the Spring and Autumn period there are sections describing the art of beekeeping, stressing the importance of the quality of the wooden box used and how this can affect the quality of the honey.[17] The Chinese word for honey (蜜 mì, reconstructed Old Chinese pronunciation *mjit) was borrowed from proto-Tocharian *ḿət(ə) (where *ḿ is palatalized; cf. Tocharian B mit), cognate with English mead.[18]

The ancient Maya domesticated a separate species of stingless bee, which they used for several purposes, including making balché, a mead-like alcoholic drink.[19] By 300 BCE they had achieved the highest levels of stingless beekeeping practices in the world.[20] The use of stingless bees is referred to as meliponiculture, named after bees of the tribe Meliponini—such as Melipona quadrifasciata in Brazil. This variation of bee keeping still occurs around the world today.[21] For instance, in Australia, the stingless bee Tetragonula carbonaria is kept for the production of honey.[22]

Scientific study of honey bees European natural philosophers began to study bee colonies scientifically in the 18th century. Preeminent among these scientific pioneers were Swammerdam, René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, Charles Bonnet, and François Huber. Swammerdam and Réaumur were among the first to use a microscope and dissection to understand the internal biology of honey bees. Réaumur was among the first to construct a glass-walled observation hive to better observe activities within hives. He observed queens laying eggs in open cells, but still had no idea of how a queen was fertilized; nobody had ever witnessed the mating of a queen and drone and many theories held that queens were \"self-fertile,\" while others believed that a vapor or \"miasma\" emanating from the drones fertilized queens without direct physical contact. Huber was the first to prove by observation and experiment that queens are physically inseminated by drones outside the confines of hives, usually a great distance away.[23]

Following Réaumur\'s design, Huber built improved glass-walled observation hives and sectional hives that could be opened like the leaves of a book. This allowed inspecting individual wax combs and greatly improved direct observation of hive activity. Although he went blind before he was twenty, Huber employed a secretary, François Burnens, to make daily observations, conduct careful experiments, and keep accurate notes over more than twenty years. Huber confirmed that a hive consists of one queen who is the mother of all the female workers and male drones in the colony. He was also the first to confirm that mating with drones takes place outside of hives and that queens are inseminated by a number of successive matings with male drones, high in the air at a great distance from their hive. Together, he and Burnens dissected bees under the microscope and were among the first to describe the ovaries and spermatheca, or sperm store, of queens as well as the penis of male drones. Huber is originally regarded as \"the father of modern bee-science\" and his \"Nouvelles Observations sur Les Abeilles (or \"New Observations on Bees\")[24] revealed all the basic scientific truths for the biology and ecology of of the movable comb hive Honey harvesting in its earliest times frequently resulted in the destruction of the whole colony as a result of the honey being taken. The wild hive was broken into, using smoke to quiet the bees. The honeycombs were pulled out and either immediately eaten whole or crushed up, along with the eggs, larvae, and honey they held. A sieve or basket was used to separate the liquid honey from the demolished brood nest. In mediaeval times in northern Europe, although skeps and other artificial containers were made to house bees, the precious honey and wax were still extracted only after killing the colony of bees.[25] It was impossible to replace old, dark-brown brood comb, in which larval bees are constricted by layers of shed pupal skins.[26]

The movable frames of modern hives are considered to be the descendants of the traditional basket top bar (movable comb) hives of Greece, which allowed the beekeeper to avoid killing the bees.[27] The oldest testimony on their use dates back to 1669 although it is probable that their use is more than 3000 years old.[28]

A beekeeper inspecting a hive frame from a Langstroth hive. Intermediate stages in the transition from the old beekeeping to the new were recorded for example by Thomas Wildman in 1768, who described advances over the destructive old skep-based beekeeping so that the bees no longer had to be killed to harvest the honey.[29] Wildman for example fixed a parallel array of wooden bars across the top of a straw hive or skep about ten inches (about 25 cm) in diameter \"so that there are in all seven bars of deal to which the bees fix their combs\", foreshadowing more modern uses of movable-comb hives. He also described using such hives in a multi-storey configuration, foreshadowing the modern use of supers: he added (at a proper time) successive straw hives below, and eventually removed the ones above when free of brood and filled with honey, so that the bees could be separately preserved at the harvest for the following season. Wildman also described a further development, using hives with \"sliding frames\" for the bees to build their comb.[30]

Wildman\'s book acknowledged the advances in knowledge of bees previously made by Swammerdam, Maraldi, and de Réaumur—he included a lengthy translation of Réaumur\'s account of the natural history of bees—and he also described the initiatives of others in designing hives for the preservation of bee-life when taking the harvest, citing in particular reports from Brittany dating from the 1750s, due to Comte de la Bourdonnaye. Another example of a hive design was invented by Rev. John Thorley in 1744. The hive was placed in a bell jar that was screwed onto a wicker basket. The bees were free to move from the basket to the jar and the honey was produced and stored in the jar. The hive was designed to keep the bees from swarming as much as they would have in other hive designs.[31]

The 19th century saw this revolution in beekeeping practice completed through the perfection of the movable comb hive by the American Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth. Langstroth was the first person to make practical use of Huber\'s earlier discovery that there was a specific spatial measurement between the wax combs, later called the bee space, which bees do not block with wax, but keep as a free passage. Having determined this bee space (commonly given as between 6 and 9 millimetres or 1⁄4 and 3⁄8 inch),[32][33] though up to 15mm has been found in populations in Ethiopia.[34] Langstroth then designed a series of wooden frames within a rectangular hive box, carefully maintaining the correct space between successive frames, and found that the bees would build parallel honeycombs in the box without bonding them to each other or to the hive walls. This enables the beekeeper to slide any frame out of the hive for inspection, without harming the bees or the comb, protecting the eggs, larvae and pupae contained within the cells. It also meant that combs containing honey could be gently removed and the honey extracted without destroying the comb. The emptied honey combs could then be returned to the bees intact for refilling. Langstroth\'s book, The Hive and Honey-bee, published in 1853, described his rediscovery of the bee space and the development of his patent movable comb hive.

The invention and development of the movable-comb-hive fostered the growth of commercial honey production on a large scale in both Europe and the US (see also Beekeeping in the United States).

Evolution of hive designs Langstroth\'s design for movable comb hives was seized upon by apiarists and inventors on both sides of the Atlantic and a wide range of moveable comb hives were designed and perfected in England, France, Germany and the United States.[35] Classic designs evolved in each country: Dadant hives and Langstroth hives are still dominant in the US; in France the De-Layens trough-hive became popular and in the UK a British National hive became standard as late as the 1930s although in Scotland the smaller Smith hive is still popular. In some Scandinavian countries and in Russia the traditional trough hive persisted until late in the 20th century and is still kept in some areas. However, the Langstroth and Dadant designs remain ubiquitous in the US and also in many parts of Europe, though Sweden, Denmark, Germany, France and Italy all have their own national hive designs. Regional variations of hive evolved to reflect the climate, floral productivity and reproductive characteristics of the various subspecies of native honey bees in each honeycomb in a wooden frame The differences in hive dimensions are insignificant in comparison to the common factors in all these hives: they are all square or rectangular; they all use movable wooden frames; they all consist of a floor, brood-box, honey super, crown-board and roof. Hives have traditionally been constructed of cedar, pine, or cypress wood, but in recent years hives made from injection molded dense polystyrene have become increasingly used.[36]

Hives also use queen excluders between the brood-box and honey supers to keep the queen from laying eggs in cells next to those containing honey intended for consumption. Also, with the advent in the 20th century of mite pests, hive floors are often replaced for part of (or the whole) year with a wire mesh and removable honey bee on a honeycomb In 2015 the Flow Hive system was invented in Australia by Cedar Anderson and his father Stuart Anderson,[37] allowing the honey to be extracted without cumbersome centrifuge equipment.

Pioneers of practical and commercial beekeeping Beekeeping has seen improvements in the design and production of beehives, systems of management and husbandry, stock improvement by selective breeding, honey extraction and marketing, in the 19th century. Notable innovators of modern beekeeping include:

Petro Prokopovych used frames with channels in the side of the woodwork; these were packed side by side in boxes that were stacked one on top of the other. The bees traveled from frame to frame and box to box via the channels.[38] The channels were similar to the cutouts in the sides of modern wooden sections.[39]

Jan Dzierżon was the father of modern apiology and apiculture. All modern beehives are descendants of his design.[40]

François Huber made significant discoveries regarding the bee life cycle and communication between bees. Despite being blind, Huber brought to light a large amount of information regarding the queen bee\'s mating habits and her contact with the rest of the hive. His work was published as New Observations on the Natural History of Bees.[41]

L. L. Langstroth revered as the \"father of American apiculture\"; no other individual has influenced modern beekeeping practice more than Lorenzo Lorraine Langstroth. His classic book The Hive and Honey-bee was published in 1853.[42]

Moses Quinby often termed \"the father of commercial beekeeping in the United States,\" author of Mysteries of Bee-Keeping Explained. He invented the Bee smoker in 1873.[43][44]

Amos Root author of the A B C of Bee Culture, which has been continuously revised and remains in print. Root pioneered the manufacture of hives and the distribution of bee-packages in the United States.[45]

A. J. Cook author of The Bee-Keepers\' Guide; or Manual of the Apiary, 1876.[46]

Dr. C.C. Miller was one of the first entrepreneurs actually to make a living from apiculture. By 1878 he made beekeeping his sole business activity. His book, Fifty Years Among the Bees, remains a classic, and his influence on bee management persists to this Extractor Franz Hruschka was an Austrian/Italian military officer who made one important invention that catalyzed the commercial honey industry. In 1865 he invented the simple machine for extracting honey from the comb by means of centrifugal force. His original idea was to support combs in a metal framework and then spin them around within a container to collect honey as it was thrown out by centrifugal force. This meant that honeycombs could be returned to a hive undamaged but empty, saving the bees a vast amount of work, time, and materials. This single invention significantly improved the efficiency of honey harvesting and catalyzed the modern honey industry.[48]

Walter T. Kelley was an American pioneer of modern beekeeping in the early and mid-20th century. He greatly improved upon beekeeping equipment and clothing and went on to manufacture these items as well as other equipment. His company sold via catalog worldwide, and his book, How to Keep Bees & Sell Honey, an introductory book of apiculture and marketing, allowed for a boom in beekeeping following World War II.[49]

In the U.K., practical beekeeping was led in the early 20th century by a few men, pre-eminently Brother Adam and his Buckfast bee and R.O.B. Manley, author of many titles, including Honey Production in the British Isles and inventor of the Manley frame, still universally popular in the U.K. Other notable British pioneers include William Herrod-Hempsall and Gale.[50][51]

Ahmed Zaky Abushady (1892–1955) was an Egyptian poet, medical doctor, bacteriologist, and bee scientist who was active in England and Egypt in the early part of the twentieth century. In 1919, Abushady patented a removable, standardized aluminum honeycomb. In 1919 he also founded The Apis Club in Benson, Oxfordshire, which was transitioned to the International Bee Research Association (IBRA). In Egypt in the 1930s, Abushady established The Bee Kingdom League and its organ, The Bee Kingdom.[52]

Modern beekeeping Horizontal hives This section is an excerpt from Horizontal top-bar hive.[edit]

Modern top bar hive A top-bar hive is a single-story frameless beehive in which the comb hangs from removable bars. The bars form a continuous roof over the comb, whereas the frames in most current hives allow space for bees to move up or down between boxes. Hives that have frames or that use honey chambers in summer but which use management principles similar to those of regular top-bar hives are sometimes also referred to as top-bar hives. Top-bar hives are rectangular in shape and are typically more than twice as wide as multi-story framed hives commonly found in English-speaking countries. Top-bar hives usually include one box only, and allow for beekeeping methods that interfere very little with the colony. While conventional advice often recommends inspecting each colony each week during the warmer months, heavy work when full supers have to be lifted,[53] some beekeepers fully inspect top-bar hives only once a year,[54] and only one comb needs to be lifted at a time.[55]

There is no single opinion leader or national standard for horizontal hives, and many different designs are used.[56] Some will accept the various standard frame sizes. Vertical stackable hives There are three types of vertical stackable hives: hanging or top-access frame, sliding or side-access frame, and top bar.

Hanging frame hives include Langstroth, the British National, Dadant, Layens, and Rose, differing primarily by size or number of frames. The Langstroth was the first successful top-opened hive with movable frames. Many other hive designs are based on the principle of bee space first described by Langstroth, and is a descendant of Jan Dzierzon\'s Polish hive designs. Langstroth hives are the most common size in the United States and much of the world; the British National is the most common size in the United Kingdom; Dadant and Modified Dadant hives are widely used in France and Italy, and Layens by some beekeepers, where their large size is an advantage. Square Dadant hives–often called 12 frame Dadant or Brother Adam hives–are used in large parts of Germany and other parts of Europe by commercial beekeepers.

Any hanging frame hive design can be built as a sliding frame design. The AZ Hive, the original sliding frame design, integrates hives using Langstroth-sized frames into a honey house so as to streamline the workflow of honey harvest by localization of labor, similar to cellular manufacturing. The honey house can be a portable trailer, allowing the beekeeper to haul the hives to a site and provide pollination services.

Top bar stackable hives simply use top bars instead of full frames. The most common type is the Warre hive, although any hive with hanging frames can be made into a top bar stackable hive by using only the top bar and not the whole frame. This may work less well with larger frames, where crosscomb and attachment can occur more often wear protective clothing to protect themselves from stings Protective clothing Most beekeepers also wear some protective clothing. Novice beekeepers usually wear gloves and a hooded suit or hat and veil. Experienced beekeepers sometimes elect not to use gloves because they inhibit delicate manipulations. The face and neck are the most important areas to protect, so most beekeepers wear at least a veil.[57] Defensive bees are attracted to the breath, and a sting on the face can lead to much more pain and swelling than a sting elsewhere, while a sting on a bare hand can usually be quickly removed by fingernail scrape to reduce the amount of venom beekeeping clothing was pale colored and this is still very common today. This is because the natural color of cotton and the cost of coloring was an expense not warranted for workwear, though some consider this is to provide better differentiation from the colony\'s natural predators (such as bears and skunks) which tend to be dark-colored. It is now known that bees see in ultraviolet and are also attracted to scent. So the type of fabric conditioner used has more impact than the color of the retained in clothing fabric continue to pump out an alarm pheromone that attracts aggressive action and further stinging attacks. Washing suits regularly, and rinsing gloved hands in vinegar minimizes smoker with heat shield and hook Main article: Bee smoker Most beekeepers use a smoker, which is a device designed to generate smoke from the incomplete combustion of various fuels. Although the exact mechanism is disputed, it is said that smoke calms bees. Some claim it initiates a feeding response in anticipation of possible hive abandonment due to fire.[60] It is also thought that smoke masks alarm pheromones released by guard bees or when bees are squashed in an inspection. The ensuing confusion creates an opportunity for the beekeeper to open the hive and work without triggering a defensive reaction.

Many types of fuel can be used in a smoker as long as it is natural and not contaminated with harmful substances. These fuels include hessian (or burlap), twine, pine needles, corrugated cardboard, and mostly rotten or punky wood. Indian beekeepers, especially in Kerala, often use coconut fibers as they are readily available, safe, and of negligible expense. Some beekeeping supply sources also sell commercial fuels like pulped paper and compressed cotton, or even aerosol cans of smoke. Other beekeepers use sumac as fuel because it ejects much smoke and lacks an odor.

Some beekeepers are using \"liquid smoke\" as a safer, more convenient alternative. It is a water-based solution that is sprayed onto the bees from a plastic spray bottle. A spray of clean water can also be used to encourage bees to move on.[61]

Torpor may also be induced by the introduction of chilled air into the hive – while chilled carbon dioxide may have harmful long-term effects.[62]

Hive tool

American hive tool Main article: Hive tool Most beekeepers use a Hive tool when working on their hives. There are two main types; the American hive tool; and the Australian hive tool often called a \'frame lifter\'.

They are used to scrape off burr-comb from around the hive, especially on top of the frames. They are also used to separate the frames before lifting out of the hive.

Effects of stings and of protective measures Some beekeepers believe that the more stings a beekeeper receives, the less irritation each causes, and they consider it important for safety of the beekeeper to be stung a few times a season. Beekeepers have high levels of antibodies (mainly IgG) reacting to the major antigen of bee venom, phospholipase A2 (PLA).[63] Antibodies correlate with the frequency of bee stings.

The entry of venom into the body from bee stings may also be hindered and reduced by protective clothing that allows the wearer to remove stings and venom sacs with a simple tug on the clothing. Although the stinger is barbed, a worker bee\'s stinger is less likely to become lodged into clothing than human skin.

Symptoms of being stung include redness, swelling, and itching around the site of the sting. In mild cases, it will take about 2 hours for the pain and swelling to subside. In moderate cases, the red welt at the sting site will become slightly larger for 1–2 days before beginning to heal. A severe reaction, which is rare among beekeepers, results in anaphylactic shock.[64]

If a beekeeper is stung by a bee, there are many protective measures that should be taken in order to make sure the affected area does not become too irritated. The first cautionary step that should be taken following a bee sting is removing the stinger without squeezing the attached venom glands. A quick scrape with a fingernail is effective and intuitive. This step is effective in making sure that the venom injected does not spread, so the side effects of the sting will go away sooner. Washing the affected area with soap and water is also a good way to stop the spread of venom. The last step that needs to be taken is to apply ice or a cold compress to the stung area.[64]

Internal temperature of a hive

Tunnel entrance with baffle The bees maintain the internal temperature of their hive at about 35 °C (95 °F).[65] Their ability to do this is known as social homeostasis and was first described by Gates.[66]

Hot weather During hot weather, the bees cool the hive by circulating cool air from the entrance up through the hive and out again;[67] and if necessary, by placing water, which they fetch, throughout the hive to create evaporative cooling.[68]

Cold weather

Hive with a second skin of polystyrene In cold weather the packing/insulation of the bee hive is essential.[69] The extra insulation reduces the amount of honey the bees consume and makes it easier for them to maintain the hive\'s ideal temperature. This need for insulation has encouraged the use of double walled hives with an outer wall of timber, or polystyrene as in the photograph; and even hives constructed from a ceramic.[70]

Location of hives There has been considerable debate about the best location for hives. Virgil thought they should be located near clear springs, ponds or shallow brooks. Wildman thought they should face to the south or west. One thing all writers agreed on is that hives should be sheltered from strong winds. In hot climates, they were often placed under the shade of trees in found that domestic honey bees placed in national parks in the USA competed with native bee species for resources. A further review of the literature concluded that large concentrations of beehives, in continents where they were not native, such as North and South America, could compete against the native bees, however, this was not as strongly observed in areas where domestic bees are native such as Europe and Africa, where the different bee species have adapted over millennia to have a narrower overlapping of forage beekeeping The natural beekeeping movement believes that bee hives are weakened by modern beekeeping and agricultural practices, such as crop spraying, hive movement, frequent hive inspections, artificial insemination of queens, routine medication, and sugar water of \"natural beekeeping\" tend to use variations of the top-bar hive, which is a simple design that retains the concept of having a movable comb without the use of frames or a foundation. The horizontal top-bar hive, as championed by Marty Hardison, Michael Bush, Philip Chandler, Dennis Murrell and others, can be seen as a modernization of hollow log hives, with the addition of wooden bars of specific width from which bees hang their combs. Its widespread adoption in recent years can be attributed to the publication in 2007 of The Barefoot Beekeeper[74] by Philip Chandler, which challenged many aspects of modern beekeeping and offered the horizontal top-bar hive as a viable alternative to the ubiquitous Langstroth-style movable-frame hive.

A vertical top-bar hive is the Warré hive, based on a design by the French priest Abbé Émile Warré (1867–1951) and popularized by Dr. David Heaf in his English translation of Warré\'s book L\'Apiculture pour Tous as Beekeeping For bee in Toronto Urban or backyard beekeeping Main article: Urban beekeeping Related to natural beekeeping, urban beekeeping is an attempt to revert to a less industrialized way of obtaining honey by utilizing small-scale colonies that pollinate urban gardens.

Some have found that \"city bees\" are actually healthier than \"rural bees\" because there are fewer pesticides and greater biodiversity in the urban gardens.[76] Urban bees may fail to find forage, however, and homeowners can use their landscapes to help feed local bee populations by planting flowers that provide nectar and pollen. An environment of year-round, uninterrupted bloom creates an ideal environment for colony beekeeping Modern beekeepers have experimented with raising bees indoors, in a controlled environment, or indoor observation hives. This may be done for reasons of space and monitoring or in the off-season. In the off-season, large commercial beekeepers may move colonies to \"wintering\" warehouses with fixed temperature, light, and humidity. This helps the bees remain healthy but relatively dormant. These relatively dormant or \"wintered\" bees survive on stored honey, and new bees are not born.[78]

Experiments in raising bees for longer durations indoors have looked into more precise and varying environment controls. In 2015, MIT\'s Synthetic Apiary project simulated springtime inside a closed environment for several hives throughout the winter. They provided food sources and simulated long days and saw activity and reproduction levels comparable to the levels seen outdoors in warm weather. They concluded that such an indoor apiary could be sustained year-round if of new colonies Colony reproduction: swarming and supersedure Main article: Swarming (honey bee)

A swarm about to land

New wax combs between basement joists All colonies are totally dependent on their queen, who is the only egg-layer. Although queens have a 3–4 year adult lifespan, diminished longevity of queens (less than 1 year) is commonly and increasingly observed.[81] She can choose whether or not to fertilize an egg as she lays it; if she does so, it develops into a female worker bee; if she lays an unfertilized egg it becomes a male drone. She decides which type of egg to lay depending on the size of the open brood cell she encounters on the comb. In a small worker cell, she lays a fertilized egg; if she finds a larger drone cell, she lays an unfertilized drone egg.[82]

All the time that the queen is fertile and laying eggs she produces a variety of pheromones, which control the behavior of the bees in the hive. These are commonly called queen substance, but there are various pheromones with different functions. As the queen ages, she begins to run out of stored sperm, and her pheromones begin to fail.[83]

Inevitably, the queen begins to falter, and the bees decide to replace her by creating a new queen from one of her worker eggs. They may do this because she has been damaged (lost a leg or an antenna), because she has run out of sperm and cannot lay fertilized eggs (has become a \"drone laying queen\"), or because her pheromones have dwindled to where they cannot control all the bees in the hive. At this juncture, the bees produce one or more queen cells by modifying existing worker cells that contain a normal female egg. They then pursue one of two ways to replace the queen: one is to supersedure, that is, replacing or superseding the queen without swarming, or, two, swarm cell production, that is, dividing the hive into two colonies through is a valued behavioral trait by some beekeepers. A hive that supersedes its old queen does not lose any stock. Instead, it creates a new queen and the old one fades away or is killed when the new queen emerges. In these hives, the bees produce just one or two queen cells, characteristically in the center of the face of a broodcomb.[85]

Swarm cell production involves creating many queen cells, typically a dozen or more. These are large, peanut-shaped protrusions requiring space, for which reason they are often located around the edges of a broodcomb, commonly at the sides and the bottom.[85]

Once either process has begun, the old queen leaves the hive with the hatching of the first queen cells. She leaves accompanied by a large number of bees, predominantly young bees (wax-secretors), who form the basis of the new hive. Scouts are sent out from the swarm to find suitable hollow trees or rock crevices. As soon as one is found, the entire swarm moves in. Within a matter of hours, they build new wax brood combs, using honey stores that the young bees have filled themselves with before leaving the old hive. Only young bees can secrete wax from special abdominal segments, and this is why swarms tend to contain more young bees. Often a number of virgin queens accompany the first swarm (the \"prime swarm\"), and the old queen is replaced as soon as a daughter queen mates and begins laying. Otherwise, she is quickly superseded in the new home.[85]

Different sub-species of Apis mellifera exhibit differing swarming characteristics. In general, the more northerly black races are said to swarm less and supersede more, whereas the more southerly yellow and grey varieties are said to swarm more frequently. The truth is complicated because of the prevalence of cross-breeding and hybridization of the swarm attached to a branch Factors that trigger swarming George S. Demuth describes the main factors that increase the swarming tendency of bees.[86] They are:

The genetics of bees; that is, how strong is the swarming instinct Congestion of the brood nest Insufficient empty combs for ripening nectar and storing honey Inadequate ventilation Having an old queen Warming weather conditions. Demuth attributed some of his comments to Snelgrove.[87]

Some beekeepers may monitor their colonies carefully in spring and watch for the appearance of queen cells, which are a dramatic signal that the colony is determined to swarm.[85]

This swarm looks for shelter. A beekeeper may capture it and introduce it into a new hive, helping meet this need. Otherwise, it reverts to a feral state, in which case it finds shelter in a hollow tree, excavation, abandoned chimney, or even behind shutters.[85]

A small after-swarm has less chance of survival and may threaten the original hive\'s survival if the number of individuals left is unsustainable. When a hive swarms despite the beekeeper\'s preventative efforts, a good management practice is to give the reduced hive a couple frames of open brood with eggs. This helps replenish the hive more quickly and gives a second opportunity to raise a queen if there is a mating failure.[85]

Each sub-species of honey bee has its own swarming characteristics. Italian bees are very prolific and inclined to swarm; Northern European black bees have a strong tendency to supersede their old queen without swarming. These differences are the result of differing evolutionary pressures in the regions where each sub-species swarming When a colony accidentally loses its queen, it is said to be \"queenless\".[88] The workers realize that the queen is absent after as little as an hour, as her pheromones fade in the hive. Instinctively, the workers select cells containing eggs aged less than three days and enlarge these cells dramatically to form \"emergency queen cells\". These appear similar to large peanut-like structures about an inch long that hang from the center or side of the brood combs. The developing larva in a queen cell is fed differently from an ordinary worker bee; in addition to the normal honey and pollen, she receives a great deal of royal jelly, a special food secreted by young \"nurse bees\" from the hypopharyngeal gland.[89] This special food dramatically alters the growth and development of the larva so that, after metamorphosis and pupation, it emerges from the cell as a queen bee. The queen is the only bee in a colony which has fully developed ovaries, and she secretes a pheromone which suppresses the normal development of ovaries in all her use the ability of the bees to produce new queens to increase their colonies in a procedure called splitting a colony.[91] To do this, they remove several brood combs from a healthy hive, taking care to leave the old queen behind. These combs must contain eggs or larvae less than three days old and be covered by young nurse bees, which care for the brood and keep it warm. These brood combs and attendant nurse bees are then placed into a small \"nucleus hive\" with other combs containing honey and pollen. As soon as the nurse bees find themselves in this new hive and realize they have no queen, they set about constructing emergency queen cells using the eggs or larvae they have in the combs with article: List of diseases of the honey bee The common agents of disease that affect adult honey bees include fungi, bacteria, protozoa, viruses, parasites, and poisons. The gross symptoms displayed by affected adult bees are very similar, whatever the cause, making it difficult for the apiarist to ascertain the causes of problems without microscopic identification of microorganisms or chemical analysis of poisons.[92] Since 2006, colony losses from colony collapse disorder have been increasing across the world although the causes of the syndrome are, as yet, unknown.[93][94] In the US, commercial beekeepers have been increasing the number of hives to deal with higher rates of apis is a microsporidian which causes the most common and widespread disease of the adult honey bee, nosemosis, also called nosema.[96]

Galleria mellonella and Achroia grisella \"wax moth\" larvae that hatch, tunnel through, and destroy comb that contains bee larvae and their honey stores. The tunnels they create are lined with silk, which entangles and starves emerging bees. Destruction of honeycombs also results in honey leaking and being wasted. A healthy hive can manage wax moths, but weak colonies, unoccupied hives, and stored frames can be decimated.[97]

Small hive beetle (Aethina tumida) is native to Africa but has now spread to most continents. It is a serious pest among honey bees unadapted to it.[98]

Varroa destructor, the Varroa mite, is an established pest of two species of honey bee through many parts of the world and is blamed by many researchers as a leading cause of CCD.[99]

Tropilaelaps mites, of which there are four species, are native to Apis dorsata, Apis laboriosa, and Apis breviligula, but spread to Apis mellifera after they were introduced to Asia.[100]

Acarapis woodi, the tracheal mite, infests the trachea of honey predators prefer not to eat honeybees due to their unpleasant sting, but they still have some predators. These include large animals such as skunks or bears, which are after the honey and brood in the nest as well as the adult bees themselves.[102] Some birds will also eat bees (for example, bee-eaters, which are named for their bee-centric diet), as do some robber flies, such as Mallophora ruficauda, which is a pest of apiculture in South America due to its habit of eating workers while they are foraging in is a town in Tioga County, New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, it had a population of 1,485.[2] The town is named after Berkshire County, Massachusetts.

The Town of Berkshire is in the northeastern part of the county and is northwest of Binghamton and southeast of rights to the Native American lands in the area were awarded to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts as part of the Boston Ten Townships, by the Treaty of Hartford in 1786. (New York retained the right to govern the land.) Massachusetts sold these rights to private individuals in 1788.

The first settlers arrived around 1791. It was originally called \"Browns Settlement.\"

The Town of Berkshire was established in 1808 from the Town of Union while in Broome County. In 1822, Berkshire was made part of Tioga County. The Town of Newark Valley, as the \"Town of Westfield,\" was created from part of Berkshire in 1828. An additional part of Berkshire was lost in 1831, to found the Town of Richford, then called \"Arlington.\"

Within the confines of Berkshire, the Lyman P. Akins House, Levi Ball House, Belcher Family Homestead and Farm, Deodatus Royce House, the J. Ball House, and the J. B. Royce House and Farm Complex, are listed on the National Register of Historic Valley Nichols Owego (county places Apalachin Crest View Heights Tioga transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the vehicles run on a prepared flat surface, rail vehicles (rolling stock) are directionally guided by the tracks on which they run. Tracks usually consist of steel rails, installed on sleepers (ties) set in ballast, on which the rolling stock, usually fitted with metal wheels, moves. Other variations are also possible, such as \"slab track\", in which the rails are fastened to a concrete foundation resting on a prepared minecart, an early example of unpowered rail transport

KTT set operating the Guangdong Through Train service on the Guangshen railway, used by the MTR Corporation, an example of modern rail transport

A DR2800 series passing Sijiaoting railway station in Ruifang District, New Taipei, Taiwan

The SL Hitoyoshi steam-hauled excursion train operating between Kumamoto and Hitoyoshi in Kyushu, Japan Part of a series on Rail transport Aiga railtransportation 25.svg HistoryTerminology (AU, NA, NZ, yardRailway track MaintenanceTrack gauge Variable gaugeGauge conversionDual gauge Rolling stock LocomotivesTrainsRailroad carsRailway couplings Couplers by countryCoupler conversionDual couplingWheelsetBogie (truck) Passenger train TramLight railRapid transit HistoryCommuter railRegional railInter-city railHigh-speed railwaysMaglev TerminologyNamed passenger countryCompaniesFreightRail subsidies Modelling icon Transport portal vte Part of a series on Transport The How and Why Library LandRailRoadMotorized cable transport RailHuman-powered CableLandRailRoadWaterMotorized land transport RailRoadPersonal rapid transitPipelineSpaceSupersonicMotorized water transportation planning and engineeringCyclabilityCycling infrastructureEngineeringFree public transportGreen transport hierarchyHistoryOutlinePublic transportSustainable transportTimelineTransport divideTransportation planning icon Transport portal vte Rolling stock in a rail transport system generally encounters lower frictional resistance than rubber-tyred road vehicles, so passenger and freight cars (carriages and wagons) can be coupled into longer trains. The operation is carried out by a railway company, providing transport between train stations or freight customer facilities. Power is provided by locomotives which either draw electric power from a railway electrification system or produce their own power, usually by diesel engines or, historically, steam engines. Most tracks are accompanied by a signalling system. Railways are a safe land transport system when compared to other forms of transport.[a] Railway transport is capable of high levels of passenger and cargo utilisation and energy efficiency, but is often less flexible and more capital-intensive than road transport, when lower traffic levels are considered.

The oldest known, man/animal-hauled railways date back to the 6th century BC in Corinth, Greece. Rail transport then commenced in mid 16th century in Germany in the form of horse-powered funiculars and wagonways. Modern rail transport commenced with the British development of the steam locomotive in Merthyr Tydfil when Richard Trevithick ran a steam locomotive and loaded wagons between Penydarren Ironworks and Abercynon in 1802. Thus the railway system in Great Britain is the oldest in the world. Built by George Stephenson and his son Robert\'s company Robert Stephenson and Company, the Locomotion No. 1 is the first steam locomotive to carry passengers on a public rail line, the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825. George Stephenson also built the first public inter-city railway line in the world to use only the steam locomotives, the Liverpool and Manchester Railway which opened in 1830. With steam engines, one could construct mainline railways, which were a key component of the Industrial Revolution. Also, railways reduced the costs of shipping, and allowed for fewer lost goods, compared with water transport, which faced occasional sinking of ships. The change from canals to railways allowed for \"national markets\" in which prices varied very little from city to city. The spread of the railway network and the use of railway timetables, led to the standardisation of time (railway time) in Britain based on Greenwich Mean Time. Prior to this, major towns and cities varied their local time relative to GMT. The invention and development of the railway in the United Kingdom was one of the most important technological inventions of the 19th century. The world\'s first underground railway, the Metropolitan Railway (part of the London Underground), opened in 1863.

In the 1880s, electrified trains were introduced, leading to electrification of tramways and rapid transit systems. Starting during the 1940s, the non-electrified railways in most countries had their steam locomotives replaced by diesel-electric locomotives, with the process being almost complete by the 2000s. During the 1960s, electrified high-speed railway systems were introduced in Japan and later in some other countries. Many countries are in the process of replacing diesel locomotives with electric locomotives, mainly due to environmental concerns, a notable example being Switzerland, which has completely electrified its network. Other forms of guided ground transport outside the traditional railway definitions, such as monorail or maglev, have been tried but have seen limited use.

Following a decline after World War II due to competition from cars and aeroplanes, rail transport has had a revival in recent decades due to road congestion and rising fuel prices, as well as governments investing in rail as a means of reducing CO2 emissions in the context of concerns about global warming.

Railroad Apiary Car & Track - Berkshire NY 1860s Bees xRARE Stereoview Photo - $595.00

|