|

On eBay Now...

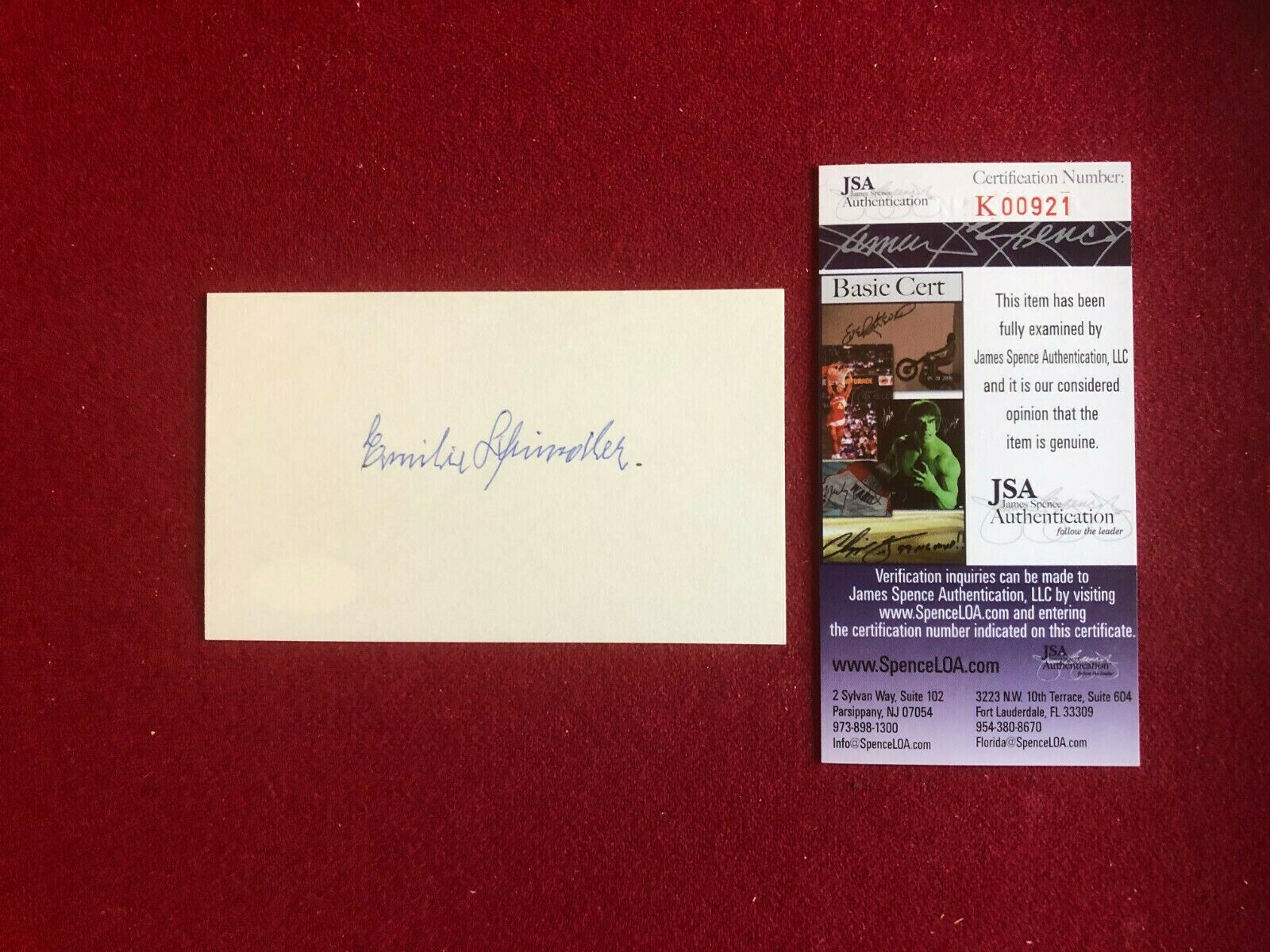

Oskar Schindler Wife COA signed JSA Index Card Vintage Scarce rescued jews WWII For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

Oskar Schindler Wife COA signed JSA Index Card Vintage Scarce rescued jews WWII:

$299.97

Emilie Schindler JSA Authenticated authenticity 3\" x 5\" Index Card signed Wife of Oskar Schindler (Schindler\'s List). Excellent Condition. Emilie Schindler was a Sudeten German-born woman who, with her husband Oskar Schindler, helped to save the lives of 1,200 Jews during World War II by employing them in his enamelware and munitions factories, providing them immunity from the Nazis. In 1962 a tree was planted in Schindler\'s honor in the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem. On June 24, 1993, Yad Vashem recognized Emilie and Oskar Schindler as Righteous Among the Schindler was born on April 28, 1908 at Zwittau/Moravia (today in the Czech Republic).His middle-class Catholic family belonged to the German-speaking community in the Sudetenland. The young Schindler, who attended German grammar school and studied engineering, was expected to follow in the footsteps of his father and take charge of the family farm-machinery plant. Some of Schindler’s schoolmates and childhood neighbors were Jews, but with none of them did he develop an intimate or lasting friendship. Like most of the German-speaking youths of the Sudetenland, he subscribed to Konrad Henlein’s Sudeten German Party, which strongly supported the Nazi Germany and actively strove for the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia and their annexation to Germany . When the Sudetenland was incorporated into Nazi Germany in 1938, Schindler became a formal member of the Nazi party.Shortly after the outbreak of war in September 1939, thirty-one-year-old Schindler showed up in occupied Krakow. The ancient city, home to some 60,000 Jews and seat of the German occupation administration, the Generalgouvernement, proved highly attractive to German entrepreneurs, hoping to capitalize on the misfortunes of the subjugated country and make a fortune. Naturally cunning and none too scrupulous, Schindler appeared at first to thrive in these surroundings. In October 1939, he took over a run-down enamelware factory that had previously belonged to a Jew. He cleverly maneuvered his steps- acting upon the shrewd commercial advice of a Polish-Jewish accountant, Isaak Stern - and began to build himself a fortune. The small concern in Zablocie outside Krakow, which started producing kitchenware for the German army, began to grow by leaps and bounds. After only three months it already had a task-force of some 250 Polish workers, among them seven Jews. By the end of 1942, it had expanded into a mammoth enamel and ammunitions production plant, occupying some 45,000 square meters and employing almost 800 men and women. Of these, 370 were Jews from the Krakow ghetto, which the Germans had established after they entered the city.A hedonist and gambler by nature, Schindler soon adopted a profligate lifestyle, carousing into the small hours of the night, hobnobbing with high ranking SS-officers, and philandering with beautiful Polish women. Schindler seemed to be no different from other Germans who had come to Poland as part of the occupation administration and their associates. The only thing that set him apart from other war-profiteers, was his humane treatment of his workers, especially the Jews.Schindler never developed any ideologically motivated resistance against the Nazi regime. However, his growing revulsion and horror at the senseless brutality of the Nazi persecution of the helpless Jewish population wrought a curious transformation in the unprincipled opportunist. Gradually, the egoistic goal of lining his pockets with money took second place to the all-consuming desire of rescuing as many of his Jews as he could from the clutches of the Nazi executioners. In the long run, in his efforts to bring his Jewish workers safely through the war, he was not only prepared to squander all his money but also to put his own life on line.Schindler’s most effective tool in this privately conceived rescue campaign was the privileged status his plant enjoyed as a “business essential to the war effort” as accorded him by the Military Armaments Inspectorate in occupied Poland. This not only qualified him to obtain lucrative military contracts, but also enabled him to draw on Jewish workers who were under the jurisdiction of the SS. When his Jewish employees were threatened with deportation to Auschwitz by the SS, he could claim exemptions for them, arguing that their removal would seriously hamper his efforts to keep up production essential to the war effort. He did not balk at falsifying the records, listing children, housewives, and lawyers as expert mechanics and metalworkers, and, in general, covering up as much as he could for unqualified or temporarily incapacitated workers.The Gestapo arrested him several times and interrogated him on charges of irregularities and of favoring Jews. However, Schindler would not desist. In 1943, at the invitation of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, he undertook a highly risky journey to Budapest, where he met with two representatives of Hungarian Jewry. He reported to them about the desperate plight of the Jews in Poland and discussed possible ways of relief.In March 1943, the Krakow ghetto was being liquidated, and all the remaining Jews were being moved to the forced-labor camp of Plaszow, outside Krakow. Schindler prevailed upon SS-Haupsturmführer Amon Goeth, the brutal camp commandant and a personal drinking companion, to allow him to set up a special sub-camp for his own Jewish workers at the factory site in Zablocie. There he was better able to keep the Jews under relatively tolerable conditions, augmenting their below-subsistence diet with food bought on the black market with his own money. The factory compound was declared out of bounds for the SS guards who kept watch over the sub-camp.In late 1944, Plaszow and all its sub-camps had to be evacuated in face of the Russian advance. Most of the camp inmates—more than 20,000 men, women, and children—were sent to extermination camps. On receiving the order to evacuate, Schindler, who had approached the appropriate section in the Supreme Command of the Army (OKW), managed to obtain official authorization to continue production in a factory that he and his wife had set up in Brünnlitz, in their native Sudetenland. The entire work force from Zablocie—to which were furtively added many new names from the Plaszow camp—was supposed to move to the new factory site. However, instead of being brought to Brünnlitz, the 800 men—among them 700 Jews—and the 300 women on Schindler’s list were diverted to Gross-Rosen and to Auschwitz, respectively.When he learned what had happened, Schindler at first managed to secure the release of the men from the Gross-Rosen camp. He then proceeded to send his personal German secretary to Auschwitz to negotiate the release of the women. The latter managed to obtain the release of the Jewish women by promising to pay 7 RM daily per worker. This is the only recorded case in the history of the extermination camp that such a large group of people were allowed to leave alive while the gas chambers were still in operation.One of the most remarkable humanitarian acts performed by Oskar and Emilie Schindler involved the case of 120 Jewish male prisoners from Goleszow, a sub-camp of Auschwitz. The men had been working there in a quarry plant that belonged to the SS-operated company “German Earth and Stone Works.” With the approach of the Russian front in January 1945, they were evacuated from Goleszow and transported westward in sealed cattle-wagons, without food or water. At the end of a seven-day grueling journey in the dead of winter, the SS guards finally stationed the two sealed cattle-cars with their human cargo at the gates of Brunnlitz. Emilie Schindler was just in time to stop the SS camp commandant from sending the train back. Schindler, who had rushed back to the camp from some food-procuring errand outside, barely managed to convince the commandant that he desperately needed the people who were locked in the train for work.When the wagons were forced open, a terrible sight was revealed. The Schindlers took charge of the 107 survivors, with terrible frostbite and frightfully emaciated, arranged for medical treatment and gradually nourished them back to life. Schindler also stood up to the Nazi Commandant who wanted to incinerate the corpses that were found frozen in the boxcars, and arranged for their burial with full Jewish religious rites in a plot of land near the Catholic cemetery, which he had especially bought for that purpose.In the final days of the war, just before the entry of the Russian army into Moravia, Schindler managed to smuggle himself back into Germany, into Allied-controlled territory. The wartime industrial tycoon was by now penniless. Jewish relief organizations and groups of survivors supported him modestly over the years, helping finance his (in the long run, unsuccessful) emigration to South America. When Schindler visited Israel in 1961, the first of seventeen visits, he was treated to an overwhelming welcome from 220 enthusiastic survivors. He continued to live partly in Israel and partly in Germany. After his death on 9 October 1974 in Hildesheim, Germany, the mournful survivors brought the remains of their rescuer to Israel to be laid to eternal rest in the Catholic Cemetery of Jerusalem. The inscription on his grave says: \'The unforgettable rescuer of 1,200 persecuted Jews\".In 1962 a tree was planted in Schindler\'s honor in the Avenue of the Righteous at Yad Vashem. On June 24, 1993, Yad Vashem recognized Emilie and Oskar Schindler as Righteous Among the Nations.Emilie Schindler (German: [eˈmiːli̯ə ˈʃɪndlɐ] ⓘ; née Pelzl [ˈpɛltsl̩]; 22 October 1907 – 5 October 2001) was a Sudeten German-born woman who, with her husband Oskar Schindler, helped to save the lives of 1,200 Jews during World War II by employing them in his enamelware and munitions factories, providing them immunity from the Nazis. She was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Israel\'s Yad Vashem in 1994.

Early lifeShe was born in the village of Maletín in Czechoslovakia, to Sudeten German farmers Josef and Marie Pelzl. She had an older brother, Franz, with whom she was very close.[2]Schindler\'s early life in Alt Moletein was idyllic, and she was quite fond of nature and animals. She was also interested in the Romani who would camp near the village for a few days at a time; their nomadic lifestyle, their music, and their stories fascinated her.[3]

MarriageEmilie Pelzl first met Oskar Schindler in 1928, when he came to Alt Moletein to sell electric motors to her father. After dating for six weeks, the couple married on 6 March 1928 in an inn on the outskirts of Svitavy, Schindler\'s hometown.[4] In spite of his flaws, Oskar had a big heart and was always ready to help whoever was in need. He was affable, kind, extremely generous and charitable, but at the same time, not mature at all. He constantly lied and deceived me, and later returned feeling sorry, like a boy caught in mischief, asking to be forgiven one more time—and then we would start all over again ... [5]World War II

See also: Holocaust

Schindler\'s factory at Brněnec in 2004In 1938, the unemployed Oskar Schindler joined the Nazi Party and moved to Kraków, leaving his wife in Svitavy. There he gained ownership of an enamelware factory that had lain idle and in bankruptcy for many years and that he renamed Deutsche Emaillewaren-Fabrik, where he principally employed Jewish workers because they were the cheapest.[6] However, he soon realized the true brutalities of the Nazis, and the Schindlers started protecting his Jewish laborers. Initially, they saved the workers by bribing the SS guards; later, they listed their employees as essential factory workers, manufacturing munitions for the Reich. When conditions worsened and they started running out of money, she sold her jewels to buy food, clothes, and medicine. She looked after sick workers in a secret sanatorium in the camp in Brněnec, Czech Protectorate, with medical equipment purchased on the black market.[5]One of the survivors, Maurice Markheim, later recalled: She got a whole truck of bread from somewhere on the black market. They called me to unload it. She was talking to the SS and because of the way she turned around and talked, I could slip a loaf under my shirt. I saw she did this on purpose. A loaf of bread at that point was gold ... There is an old expression: Behind the man, there is the woman, and I believe she was the great human being.[5]The Schindlers saved more than 1,200 Jews from extermination camps. In May 1945, when the Soviets moved into Brünnlitz, the Schindlers left the Jews in the factory and went into hiding, in fear of being prosecuted because of Oskar\'s ties with the Nazi party.[5]

Life after the warThe Schindlers fled to Buenos Aires, Argentina, with a dozen of the Schindler Jews. In 1949, they settled there as farmers and were supported financially by a Jewish organization.[7]In 1957, a bankrupt Oskar Schindler abandoned his wife and returned to Germany, where he died in 1974.[8] Although they never divorced, they also never saw each other again. In 1993, during the production of the film Schindler\'s List, Emilie Schindler and a number of surviving Schindler Jews visited her husband\'s grave in Jerusalem; she was accompanied by Caroline Goodall, the actress who portrayed her in the film. At last we meet again ... I have received no answer, my dear, I do not know why you abandoned me ... But what not even your death or my old age can change is that we are still married, this is how we are before God. I have forgiven you everything, everything ...[5]After the film\'s release, Emilie\'s close friend and biographer, Erika Rosenberg, quoted Emilie in her book as saying that the filmmakers had paid \"not a penny\" to Emilie for her contributions to the film. These claims were disputed by Thomas Keneally, author of Schindler\'s Ark, who claimed he had recently sent Emilie a cheque of his own, and that he had gotten into an argument with Rosenberg over this issue before Emilie angrily told Rosenberg to drop the subject.[9] In his 2001 film In Praise of Love, filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard accuses Steven Spielberg of neglecting Emilie while she was supposedly dying, impoverished, in Argentina.[10] In response to Godard, film critic Roger Ebert mused, \"Has Godard, having also used her, sent her any money?\" and \"Has Godard or any other director living or dead done more than Spielberg, with his Holocaust Project, to honor and preserve the memories of the survivors?\"[10][11]Schindler lived with her 50 pets for many years in her small house in San Vicente, 40 kilometres south-west of Buenos Aires. She received a small pension from Israel and Germany. Uniformed Argentinian police were posted 24 hours a day to protect her from anti-Semitic extremist groups. She formed friendships with many of the soldiers.[5]

DeathIn July 2001, during a visit to Berlin, Schindler told reporters that it was her \"greatest and last wish\" to spend her final years in Germany, adding that she had become increasingly homesick.[5] She died at the age of 93 from the effects of a stroke in Märkisch-Oderland Hospital, Strausberg, on the night of 5 October 2001, 2½ weeks before her 94th birthday.[12] Her only relative was a niece in Bavaria. She is buried at the cemetery in Waldkraiburg, Germany, about an hour away from Munich. Her tombstone includes the words from the Mishnah, Sanhedrin 4:5, Wer einen Menschen rettet, rettet die Ganze Welt (\"Whoever saves one life, saves the entire world.\").[13]

LegacySchindler was honored by several Jewish organizations for her efforts during World War II. In May 1994, she and her husband received the title Righteous Among the Nations from Yad Vashem,[14][15] along with Miep Gies, the woman who hid Anne Frank and her family in the Netherlands during the war. In 1995, she was decorated with the Order of May, the highest honor given to foreigners who are not heads of state in Argentina.[5] Her life inspired Erika Rosenberg\'s book Where Light and Shadow Meet, first published in Spanish in 1992 and later made available in English and German translations.She appears in the Thomas Keneally novel Schindler\'s Ark and the 1993 film based on it, Schindler\'s List, in which she is played by Caroline Goodall.She is the subject of the opera Frau Schindler by composer Thomas Morse, which premiered in 2017 at the Gärtnerplatz Theater in Munich.[16] The following year a new production of the opera, directed by Vladimir Alenikov, was produced at the Stanislavsky Nemirovich-Danchenko Theatre for their hundredth anniversary season.[17]

See also Individuals and groups assisting Jews during the Holocaust

List of Righteous among the Nations by countryThis tiny white-haired woman, gentle and courageous, showed us an intriguing glimpse at the shadow world between memory and legend. Her husband Oscar Schindler became a household name as one of the great humanitarians of the century, saving 1,300 Jews from certain death in the Nazi death camps during World War II. While Oscar Schindler\'s efforts to save hundreds of Jews are well known thanks to Keneally\'s book and the movie Schindler\'s List, the silver-screen version left Emilie on the sidelines. An unsung heroine. Now a new German-language book Ich, Emilie Schindler by the Argentinian author Erika Rosenberg tries to show that Emilie was just as involved in shielding Jews from the Nazis. Emilie Schindler - PhotosThe biography highlights Emilie Schindler\'s bravery during the Holocaust and portrays her not only as a strong woman working alongside her husband but as a heroine in her own right. Erika Rosenberg, a journalist who befriended Emilie Schindler 11 years ago, is writing the book to fulfil one of the old widow\'s last wishes, to tell her story and to correct a historical oversight. For Emilie Schindler, the book is about finding peace. As Rosenberg says: \'She\'s looking for recognition. Not in the form of money, but recognition for her service .. to be the same like her husband.\'For the last five decades Emilie Schindler led a modest existence in her little house in San Vicente 40 kilometres south-west of Buenos Aires with her cats, dog and beautiful roses. Only the uniformed Argentinean police disturbed the idyll. They were posted 24 hours a day to protect the old lady from anti-Semitic and ultra-Conservative extremist groups. Emilie Pelzl was born on October 22, 1907, in the city of Alt Moletein, a village in the German-populated border region of what was then The Republic of Czechoslovakia. Emilie later recalled the local pastor, an old family friend, who instructed young Emilie that her friendship with a young Jew, Rita Reif, was not good. Emilie defied the pastor and retained her friendship with Rita, until Rita was murdered by the Nazis in front of her father\'s store in 1942.Emilie Pelzl first saw the tall, handsome and outgoing Oscar Schindler when he came to the door of her father\'s farmhouse in Alt Moletein. It was 1928 and Oscar was selling electric motors. After a courtship of six weeks, they were married on March 6, 1928, in an inn on the outskirts of Zwittau, Oscar\'s hometown. Emilie\'s father had given Oscar a dowry of 100.000 Czech crowns, a considerable sum in those days, and he soon bought a luxury car and squandered the rest on outings. In her A Memoir Where Light And Shadow Meet Emilie recalls how she struggled trying to understand him:In spite of his flaws, Oscar had a big heart and was always ready to help whoever was in need. He was affable, kind, extremely generous and charitable, but at the same time, not mature at all. He constantly lied and deceived me, and later returned feeling sorry, like a boy caught in mischief, asking to be forgiven one more time - and then we would start all over again ...Emilie and Oscar SchindlerIn the thirties, now without employment, Oscar Schindler joined the Nazi party, as did many others at that time. Maybe because he had seen possibilities which the war brought in its wake, he followed on the heels of the SS when the Germans invaded Poland.He left Emilie in Zwittau and moved to Crakow, where he took over a Jewish family`s apartment. Bribes in the shape of money and illegal black market goods flowed copiously from Schindler and gave him control of a Jewish-owned enameled-goods factory, Deutsch Emailwaren Fabrik, close to the Jewish ghetto, where he principally employed Jewish workers. At this time presumably because they were the cheapest labour ...But slowly as the brutality of the Nazis accelerated with murder, violence and terror, the seeds of their plan for the total extermination of the Jews dawned on Schindler in all its horror - he came to see the Jews not only as cheap labour, but also as mothers, fathers, and children, exposed to ruthless slaughter. So with help from Emilie he decided to risk everything in desperate attempts to save the 1300 Schindler Jews from certain death in the hell of the death camps. Thanks to massive bribery and Oscar\'s connections, they got away with actively protecting their workers.Schindler promised the Jews who worked for him that they would never starve, that he would protect them as best he could. And he did, building his own workers barracks on the factory grounds to help alleviate the sufferings of life in the nearby Plaszow labor camp. He gave safe haven to as many Jewish workers as possible, insisting to the occupying Nazis that they were \"essential workers\", a status that kept them away from harassment and killings.Oscar SchindlerAt Schindler`s factory, nobody was hit, nobody murdered, nobody sent to death camps. But conditions at the factory were far from comfortable. Freezing, lice-ridden inmates still suffered typhus and dysentery.Until the liberation of spring, 1945, the Schindler\'s used all means at their disposal to ensure the safety of the Schindler-Jews. They spent every pfennig they had, and even Emilie\'s jewels were sold, to buy food, clothes, and medicine. They set up a secret sanatorium in the factory with medical equipment purchased on the black market. Here Emilie looked after the sick. Those who did not survive were given a fitting Jewish burial in a hidden graveyard - established and paid for by the Schindlers.Later accounts have revealed that the Schindlers spent something like 4 million German marks keeping their Jews out of the death camps - an enormous sum of money for those times.The factory continued to produce shells for the German Wehrmacht for 7 months. In all that time not one usable shell was produced! Not one shell passed the military quality tests. Instead, false military travel passes and ration cards were produced, just as Nazi uniforms, weapons, ammunition and hand-grenades were collected. The horrors of The HolocaustOne night in the last weeks of the war a tireless Emilie, acting alone while Oscar was in Crakow, saved 250 Jews from impending death. Emilie was confronted by Nazis transporting the Jews, crowded into four wagons, from Golechau to a death camp. She succeeded in persuading the Gestapo to send these Jews to the factory camp \"with regard to the continuing war industry production\". In her A Memoir she recalls:We found the railroad car bolts frozen solid .. the spectacle I saw was a nightmare almost beyond imagination. It was impossible to distinguish the men from the women: they were all so emaciated - weighing under seventy pounds most of them, they looked like skeletons. Their eyes were shining like glowing coals in the dark ..Each had to be carried out like a carcass of frozen beef. Thirteen were dead but the others still breathed. Throughout that night and for many nights following, Emilie worked without halt on the frozen and starved skeletons. One large room in the factory was emptied for the purpose. Three more men died, but with the care, the warmth, the milk and the medicine, the others gradually rallied. After the war survivors told about Emilie\'s unforgettable heroism in nursing the frozen and starved prisoners back to life ..Emilie Schindler is credited with many acts of kindness, small and large. Even today surviving Schindler-Jews remember how Emilie worked indefatigably to secure food and somehow managed to provide the sick with extra nourishment and apples. A Jewish boy, Lew Feigenbaum, broke his eyeglasses and stopped Emilie in the factory and told her: \"I broke my glasses and can\'t see ..\" When the Schindler-Jews were transferred to Brunnlitz, Emilie arranged for a prescription for the eyeglasses to be picked up in Crakow and delivered to her in Brunnlitz. Feiwel (today Franciso) Wichter, 75, was No. 371 on Schindler\'s List, the only one of the Schindler Jews living in Argentina: As long as I live, I will always have a sincere and eternal gratitude for dear Emilie. I think she triumphed over danger because of her courage, intelligence and determination to do the right and humane thing. She had immense energy and she was like a mother.Another survivor, Maurice Markheim, No.142 on the list, later recalled:She got a whole truck of bread from somewhere on the black market. They called me to unload it. She was talking to the SS and because of the way she turned around and talked, I could slip a loaf under my shirt. I saw she did this on purpose. A loaf of bread at that point was gold .. There is an old expression: Behind the man, there is the woman, and I believe she was the great human being.In May, 1945, it was all over. The Russians moved into Brunnlitz. The previous evening, Schindler gathered everyone together in the factory, where he and Emilie took a deeply emotional leave of them.The Schindlers - and 1300 Schindler-Jews along with them - had survived ....Schindler with the RosnersOscar Schindler`s life after the war was a long series of failures. He tried without success to be a film producer and was deprived of his nationality immediately after the war. Threats from former Nazis meant that he felt insecure in post-war Germany, and he applied for an entry permit to the United States. This was refused as he had been a member of the Nazi party.After this he fled to Buenos Aires in Argentina with Emilie, his mistress and a dozen Schindler Jews. The Schindlers settled down in 1949 as farmers, first raising chickens and then nutrias. They were supported financially by the Jewish organization Joint and thankful Jews, who never forgot them. But Oscar Schindler met with no success, and in 1957 he became bankrupt and travelled back alone to Germany, where he remained estranged from his wife for 17 years before he died in poverty in 1974, at the age of 66. He never saw Emilie again ...Emilie stayed in Argentina, where she scraped by on a small pension from Israel and a $650 a month pension from Germany. Her only relative, a niece, lived in Bavaria, Germany.Jewish organizations have honored her for her efforts during the war. In May, 1994, Emilie Schindler received The Righteous Amongst the Nations Award - along with Miep Gies, who hid Anne Frank\'s family in the Netherlands and preserved her diary after the family was taken away by the Nazis.Almost 2,000 people attended the Simon Wiesenthal Center\'s Yom Hashoah commemoration honoring Emilie Schindler. The tiny woman in the navy blue pantsuit was greeted with smiles and tears as she made her way, supported by two rabbis, toward the menorah-shaped monument at the Museum of Tolerance, where she lit the memorial flame to remember the 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust. \'Let me touch you,\' said one woman as she reached out to embrace Emilie Schindler.In 1995, Argentina decorated her with the Order of May, the highest honor given to foreigners who are not heads of state. In 1998 The Argentine government decided to give her a pension of $1,000 a month until her financial situation improved. Last November, Emilie Schindler, was named an Illustrious Citizen by Argentina.Emilie fell last Nov. 1 at her home in San Vicente. She lay for hours, alone. After undergoing a hip replacement operation, Emilie had to enter a home for the elderly in Buenos Aires, her care heavily subsidized by Argentine charities. Hospital officials had delayed her surgery for three days because she could not afford the operation. Financiel help eventually came from several soccer players, River Plate, and other Argentine citizens.In July, 2001, during a visit to Berlin, Germany, a frail Emilie handed over documents related to her husband to a museum. Confined to a wheelchair and totally dependent upon others, she told reporters that it was her \'greatest and last wish\' to spend her final years in Germany, adding that she had become increasingly homesick. \'I am very happy that I can be here,\' she told with a dazzling smile.Her Argentinian biographer Erika Rosenberg said she was urgently seeking a German home for Schindler\'s widow. \'Now, as an old lady, Emilie Schindler needs help herself for the first time,\' Rosenberg said. The German state of Bavaria immediately offered a home to Emilie Schindler. Bavaria would be happy to help fulfill her wish, Bernhard Seidenath, a spokesman for the Ministry of Social Affairs, said Monday July 16, 2001. Emilie Schindler - an unsung heroineA deeply grateful Emilie accepted the offer. She will be taken Sunday July 22, 2001, to the Adalbert Founder Home in the Bavarian town of Waldkraiburg by ambulance from Berlin, said Joerg Kudlich, head of the home.But the plans to transport her to the retirement home was put on hold as she was hospitalized in critical condition on saturday July 21. Mrs. Schindler is in intensive care, a transport is out of the question, said Dr. Hans Pech, head of interior medicine at the Maerkisch-Oderland Hospital outside Berlin. Emilie Schindler died Friday night October 5, 2001, in the Berlin hospital.The coffin of Emilie Schindler in the cemetery of Waldkraiburg, southern Germany, Friday, Oct. 19, 2001, during the funeralThe famous Argentine journalist Sol tells that one of her favourites interviews was on radio with Emilie Schindler:\'When I talked with her I felt a great spirit of love and wisdom in her words. She\'s a great woman, a woman of courage and a woman of love and compassion for others. She did much more than the movie presents.\'As to Oscar Schindler the author Erika Rosenberg had no doubt: \'Emilie still loved Oscar Schindler\', though Emilie was bitter and disillusioned: \'He gave his Jews everything - and me, nothing.\' But she was capable of expressing both her love and bitterness towards him in one sentence, calling him a drunk and womanisor, but also saying: \'If he\'d stayed, I\'d have looked after him.\'In A Memoir Emilie tells about her inner thoughts, when she visited his tomb, over thirty-seven years after he left:\"At last we meet again .. I have received no answer, my dear, I do not know why you abandoned me .. But what not even your death or my old age can change is that we are still married, this is how we are before God. I have forgiven you everything, everything .. \"Emilie Schindler, who helped her industrialist husband save hundreds of Jews from Nazi death camps in a saga memorialized by the movie \'\'Schindler\'s List,\'\' died on Friday night, her biographer said on Saturday. She was 93.She died in a hospital in Strausberg, outside Berlin, where she had been since July 21, said the biographer, Erika Rosenberg.The Schindlers, who saved at least 1,200 Jews, were celebrated in Steven Spielberg\'s Oscar-winning film in 1993.Ms. Schindler had contended, though, that the film overlooked her role in keeping the Jews alive. \'\'Oskar is the hero -- and what about me?\'\' she told German ARD television in a 1999 interview. \'\'I saved many Jews, too.\'\'According to the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, Yad Vashem, which gave her the \'\'Righteous Among the Nations\'\' award in 1993, Ms. Schindler prevented the Nazis from sending a trainload of 120 nearly starved Jewish prisoners to Auschwitz.Oskar Schindler convinced the Nazi SS camp commander that the emaciated, frostbitten men were needed to work in his factory. Upon their arrival, Ms. Schindler nursed them back to health. None of them ever worked.Ms. Schindler, who had lived in Argentina since 1949, came to Germany this year saying she wanted to spend her final days here. A retirement home in Bavaria accepted her, but she fell ill and was hospitalized at the Märkisch-Oderland clinic.She was born in a German-speaking village in today\'s Czech Republic, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. She married Mr. Schindler in 1928 and moved with him to Krakow, Poland, where they ran a factory later used to harbor Jewish laborers during World War II.The Schindlers immigrated to Argentina after the war, but Mr. Schindler returned to Germany in 1958, leaving his wife behind. Though they never saw each other again, they never divorced. Mr. Schindler died in 1974.They had no children, and for decades, Ms. Schindler lived alone in Argentina, subsisting on a state pension until the film brought her more attention. She was awarded Argentina\'s highest honor granted to foreigners, the Order of May, in 1995.In her memoir, \'\'Where Light and Shadow Meet,\'\' written with Ms. Rosenberg and published by Norton, Ms. Schindler portrayed her husband as a womanizer and as self-serving as he was generous.Her own recollections of scrounging for bread and medicine on the black market and begging for food for the Jewish laborers they kept were detailed in the book, illustrating her claims that her husband had not single-handedly saved their lives.After returning to Germany in July, she donated papers and other items that belonged to her husband to a history museum in Bonn.Earlier, she lost a legal battle to obtain a suitcase full of her husband\'s papers, including a list of the Jews who were saved, that a German couple found in 1999 and gave to the Stuttgarter Zeitung. The paper published excerpts, then donated the papers to Yad Vashem.Ms. Schindler is survived by a niece in Germany.As Israel marks its annual Holocaust Remembrance Day, one of those whose lives were saved by German businessman Oskar Schindler has spoken of his lasting gratitude.Mr Schindler is credited with rescuing nearly 1,200 Jews, whom he employed in his enamel and munitions factory in Krakow, in German-occupied Poland, shielding them from deportation to death camps.Dr Jonathan Dresner, 85, who has lived in Israel since 1949, was one of those on Mr Schindler\'s list of Jewish workers protected from the SS.\"All those who were on Schindler\'s list were lucky people and we felt it at that time,\" he said.\"When we saw Schindler walking around we felt safe. It was everything for us. It is the main reason why I am alive today, how I was able to build a new life after the war.\"Dr Dresner says he remembers Mr Schindler as a \"very handsome, charming man\" who naturally engendered trust.\"He used his charm especially on women, and he used it very well, and when you looked at him his face told you that you could rely on him,\" he said.\'Nazis bribed\'Along with his sister and parents, Dr Dresner was sent from Krakow\'s Jewish ghetto to work in Mr Schindler\'s factory.\"Everybody who was young enough and strong enough had to work and mostly people were working for the Germans - we were forced to do it, but this was the way that we thought at that time that we could survive,\" he said.

My grandchild was [once] asked what she thought of Schindler and she said she felt that he saved her also

Dr Jonathan Dresner

Mr Schindler saved his workers, known as the Schindlerjuden, from the camps by using charm and guile and by bribing Nazi officials.\"He bribed everybody in Berlin and he got his permission,\" recalled Mr Dresner.\"He told them he needs special men and women who will do the work he needs... 800 men and 300 women, and this was how Schindler\'s list was born.\"The story was immortalised in the book Schindler\'s Ark by Thomas Keneally and the film Schindler\'s List by Steven Spielberg.Mr Dresner\'s family was one of only four which worked for Mr Schindler and survived.\'We owe him\'By the end of the war, Mr Schindler was virtually destitute and spent the following decades drifting from one failed business venture to another.\"We [Schindler\'s surviving Jewish workers] decided to give him a monthly pension,\" said Mr Dresner.\"[But] it wasn\'t enough for him because he was what he was - a drinker and a womaniser. When he got $100 he spent $110. He went bankrupt and he was left with a lot of debts.\"At that time we, the survivors, especially those who were living in Israel, organised ourselves and we decided that we\'d take care of him,\" he said.Mr Schindler died in 1974, aged 66, and was buried in Jerusalem in accordance with his wishes.Mr Dresner - one of only about 60 Jews saved by Mr Schindler still alive - says the legacy of his actions continues to be felt.\"My grandchild was [once] asked what she thought of Schindler and she said she felt that he saved her also,\" he said.\"We feel all the time that we owe him and we want him to know that we owe him.\"The story of Schindler and Stern, the central figures in Steven Spielberg\'s film Schindler\'s List, became known to the world at large primarily through Thomas Keneally\'s 1982 novel Schindler\'s Ark. Keneally, an Australian, never met Schindler, who died in 1974, but thirteen years ago in Los Angeles he did meet one of the more than 1,000 Jews whom Schindler had saved from the gas chambers. This chance encounter set him off on his research. Although Keneally\'s book about the opportunistic Nazi businessman who ended up redeeming himself at the vortex of the Holocaust was factual, he decided to call it a novel because of the imagined or \"re-created\" dialogue that he felt was necessary to the narrative.Unknown to Keneally or Spielberg, another writer--a Canadian-- had stumbled on the Schindler story nearly forty-six years ago. Herbert Steinhouse, a Montreal-born journalist, novelist, and broadcaster, flew with the RCAF during the war and afterwards became an information officer for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA). While stationed in Paris, he signed on with Reuters but in 1949 jumped to the CBC as its Paris bureau chief.It was a few months earlier, in Munich, that he first met Schindler. He had already fallen in with some of the Holocaust survivors Schindler had saved--the so called Schindlerjuden--and they had begun telling him some of their stories. Given his stint at UNRRA, Steinhouse was suspicious of \"good German\" tales, but he was sufficiently intrigued this time to begin looking for independent verification.Steinhouse was led to Schindler himself by two Polish Jews who had decided that their rescuer\'s security and best hope for the future lay in maximum publicity for his remarkable wartime story. This was especially so since be was still classified as a \"former Nazi,\" which severely limited his chances of emigrating to most countries. \"Schindler charmed me as he did everyone,\" Steinhouse recalls. \"Our wives also hit it off. We dined together and drank together. He talked, I made notes.\"The story continued to strike Steinhouse as \"far-fetched,\" but he found more and more corroboration both in survivors\' recollections and in underground and resistance files. Finally, after a half-dozen sessions with Itzhak Stern, who was his principal source, four interviews with Schindler, and professional pictures taken by a close friend (now deceased) named Al Taylor, Steinhouse set to work and wrote his exclusive in the form of a magazine article which he dispatched to his New York agent.The agent couldn\'t place it. Steinhouse, who is now seventy-two and retired in Montreal, recalls various reasons for its rejection: reflecting his own initial scepticism, magazines didn\'t want another story on a \"good German\"; the Holocaust was thought to have grown wearying to readers; magazine editors were trying to give their publications an optimistic look ahead into the fifties, not a bleak rearward gaze to the wretched forties. Consequently, Herbert Steinhouse\'s account Of Oskar Schindler has gone on sitting unread in his files for most of half a century. Though somewhat shortened, it is now being published for the first time in Saturday Night, a publication to which the I writer was once a contributor on international affairs. Ironically, he may even have offered the magazine his article on Schindler at that time. In reading it you will want to remember that Steinhouse was writing about events that had reached their conclusion only four years earlier. It remains an important document for several reasons: for the corroboration it gives to the established record; for the further details and anecdotes not contained in either Keneally\'s novel or Spielberg\'s film; and, most importantly, for the direct and remarkable access it gives readers to Oskar Schindler himself.It was from the accountant Itzhak Stem that I first heard of Oskar Schindler. They had met in Cracow in 1939. \"I must admit now that I was intensely suspicious of Schindler for a long time,\" Stern confided, beginning his story. \"I suffered greatly under the Nazis. I lost my mother in Auschwitz quite early and I was very embittered.\"At the end of 1939, Stern directed the accountancy section of a large Jewish-owned export-import firm, a position he had held since 1924. After the occupation of Poland in September, the head of each important Jewish business was replaced by a German trustee, or Treuhander, and Stern\'s new boss became a man named Herr Aue. The former owner, as was the requirement, became an employee, the firm became German, and Aryan workers were brought in to replace many of the Jews.Aue\'s behaviour was inconsistent and immediately aroused Stern\'s curiosity. Although he had begun Aryanizing the firm and firing the Jewish workers in accordance with his instructions, he nevertheless left the discharged employees\' names on the social-insurance registry, thus enabling them to maintain their all-important workers\' identity cards. As well, Aue secretly gave these hungry men money. Such exemplary behaviour could only impress the Jews and astonish the wary and cautious Stern. Only at the end of the war was Stern to learn that Aue had been Jewish himself, that his own father was murdered in Auschwitz in 1942, and that the Polish he pretended to speak so poorly actually was his native tongue.Not knowing all this, Stern had no reason to trust Aue. Certainly he could not understand the man\'s presumption when, only a few days after having taken charge of the export-import firm, Aue brought in an old friend who had just arrived in Cracow to see Stern saying, quite casually, \"You know, Stem, you can have confidence in my friend Schindler.\" Stern exchanged courtesies with the visitor, and answered his questions with care.\"I did not know what he wanted and I was frightened,\" Stern continued. \"Until December 1, we Polish Jews had been left more or less alone. They had Aryanized the factories, of course. And if a German asked you a question in the street it was compulsory for you to precede your answer with I am a Jew....\' But it was only on December 1 that we had to begin wearing the Star of David. It was just as the situation had begun to grow worse for the Jews, when the Sword of Damocles was already over our heads, that I had this meeting with Oskar Schindler.\"He wanted to know what land of Jew I was. He asked me many questions, like was I a Zionist or assimilated or what have you. I told him what everyone knew, that I was vice president of the Jewish Agency for Western Poland and a member of the Zionist Central Committee. Then he thanked me politely and went away.\"On December 3, Schindler paid another visit to Stern, this time at night and to his home. They talked chiefly of literature, Stern remembers, and Schindler revealed an unusual interest in the great Yiddish writers. And then suddenly, over some tea, Schindler remarked: \"I hear that there will be a raid on all remaining Jewish property tomorrow.\" Recognizing the intended warning, Stem later passed the word around and effectively saved many friends from the most ruthless \"control\" the Germans had thus far carried out. Schindler, he realized, had been attempting to encourage his confidence, although he could still not fathom why.Oskar Schindler, a Sudeten industrialist, had come to Cracow from his native town of Zwittau, just across what had been a border a few months earlier. Unlike most of the carpetbaggers who joyously rushed into prostrate Poland to gobble up the nation\'s production, he received a factory not from an expropriated Jew but from the Court of Commercial Claims. A small concern devoted to the manufacture of enamel-ware, it had lain idle and in bankruptcy for many years. In the winter of 1939-1940 he began operations with 4,000 square metres of floor space and a hundred workers, of whom seven were Jewish. Soon he managed to bring in Stern as his accountant.Production started with a rush, for Schindler was a shrewd and tireless worker, and labour--by now semi-slave--was as plentiful and as cheap as in any industrialist\'s fondest dream. During the first year the labour force expanded to 300, including 150 Jews. By the end of 1942, the factory had grown to 45,000 square metres and employed almost 800 men and women. The Jewish workers, of whom there were now 370, all came from the Cracow ghetto the Germans had created. \"It had become a tremendous advantage,\" says Stem, \"to be able to leave the ghetto in the daytime and work in a German factory.\"Relations between Schindler and the Jewish workers began and continued on a circumspect plane. In these early days he had little contact with all save the few who, like Stern, worked in the offices. But comparing their lot with that of the Jews trapped in the ghetto, from which deportations had by now begun, or even with those who slaved for other Germans in neighbouring factories, Schindler\'s Jewish workers grew to appreciate their position. Although they could not understand the reasons, they recognized that Herr Direktor was somehow protecting them. An air of quasi-security grew in the factory and the men soon sought permission to bring in families and friends to share in their comparative haven.Word spread among Cracow s Jews that Schindler\'s factory was the place to work. And, although the workers did not know it, Schindler helped his Jewish employees by falsifying the, factory records. Old people were recorded as being twenty years younger; children were listed as adults. Lawyers, doctors, and engineers were registered as metalworkers, mechanics, and draughtsmen--all trades considered essential to war production. Countless lives were saved in this manner as the workers were protected from the extermination commissions that periodically scrutinized Schindler s records.At the same time, most of the workers did not know that Schindler spent his evenings entertaining many of the local SS and Wehrmacht officers, cultivating influential friends and strengthening his position wherever possible. His easy charm passed as candour, and his personality and seeming political reliability made him popular in Nazi social circles in Cracow.Stern remained unimpressed by the air of security. They were all perched on a volcano s edge, he knew. From behind his high book-keeper s table he could see through the glass door of Schindler s private office. \"Almost everyday, from morning until evening, officials and other visitors came to the factory and made me nervous. Schindler used to keep pouring them vodka and joking with them. When they left he would ask me in, close the door, and then quietly tell me whatever they had come for. He used to tell them that he knew how to get work out of these Jews and that he wanted more brought in. That was how we managed to get in the families and relatives all the time and save them from deportation.\" Schindler never offered explanations and never revealed himself as a die-hard antifascist, but gradually Stern began to trust him.SCHINDLER maintained personal links to \"his Jews,\" each of whom worked in the factory s office. One was Itzhak Stern s brother, Dr. Nathan Stern, a man who is today a respected member of Poland s small Jewish community. Magister Label Salpeter and Samuel Wulkan, both old ranking members of the Polish Zionist movement, were the other two. Together with Stern, they were part of a group that served as a link with the outside underground movement. And in this work they were soon joined by a man named Hildegeist, the former leader of the Socialist Workers Union in his native Austria, who, after three years in Buchenwald, had been taken on in the factory as an accountant. A factory worker, the engineer Pawlik, subsequently to reveal himself as an officer in the Polish underground, led these activities.Schindler himself played no active role in all this, but his protection served to shelter the group. It is doubtful that these few men did effective resistance work, but he group did provide the Schindlerjuden with their first cohesiveness and a semblance of discipline that later was to prove useful.While friends and parents in the ghetto were being murdered in the streets or were dying of disease or were being sent to nearby Auschwitz, daily life in the factory continued in this minor key until 1943. Then, on March 13, came all the orders to close the Cracow ghetto. All Jews were moved to the forced-labor camp of Plaszow, outside the city. Here, in a sprawling series of installations that included subordinate camps throughout the region, conditions even for the graduates of the terrible Cracow ghetto were shocking. The prisoners suffered and by the hundreds either died in camp or were moved to Auschwitz. The order to complete the extermination of Jewry had already been given and willing hands on all sides cooperated to carry out the command as efficiently and quickly as possible.Stern along with Schindler s other workers had also been moved to Plaszow from the ghetto but, like some 25,000 other inmates who inhabited the camp and worked outside, they continued spending their days in the factory. Falling deathly ill one day, Stern sent word to Schindler urgently pleading for help. Schindler came at once, bringing essential medicine, and continued his visits until Stern recovered. But what he had seen in Plaszow had chilled him.Nor did he like the turn things had taken in his factory.Increasingly helpless before the frenetic Jew-haters and Jew-destroyers, Schindler found that he could no longer joke easily with the German officials who came on inspections. The double game was becoming more difficult. Incidents happened more and more often. On one occasion, three SS men walked onto the factory floor without warning, arguing among themselves. \"I tell you, the Jew is even lower than an animal,\" one was saying. Then, taking out his pistol, he ordered the nearest Jewish worker to leave his machine and pick up some sweepings from the floor. \"Eat it,\" he barked, waving his gun. The shivering man choked down the mess. \"You see what I mean,\" the SS man explained to his friends as they walked away. \"They eat anything at all. Even an animal would never do that.\"Another time, during an inspection by an official SS commission, the attention of the visitors was caught by the sight of the old Jew, Lamus, who was dragging himself across the factory courtyard in an utterly depressed state. The head of the commission asked why the man was so sad, and it was explained to him that Lamus had lost his wife and only child a few weeks earlier during the evacuation of the ghetto. Deeply touched, the commander reacted by ordering his adjutant to shoot the Jew \"so that he might be reunited with his family in heaven,\" then he guffawed and the commission moved on. Schindler was left standing with Lamus and the adjutant.\"Slip your pants down to your ankles and start walking,\" the adjutant ordered Lamus. Dazed, the man did as he was told.\"You are interfering with all my discipline here,\" Schindler said desperately. The SS officer sneered.\"The morale of my workers will suffer. Production for der Vaterland will be affected.\" Schindler blurted out the words. The officer took out his gun.\"A bottle of schnapps if you don\'t shoot him\", Schindler almost screamed, no longer thinking rationally.\"Stimmt!\" To his astonishment, the man complied. Grinning, the officer put the gun away and strolled arm in arm with the shaken Schindler to the office to collect his bottle. And Lamus, trailing his pants along the ground, continued shuffling across the yard, waiting sickeningly for the bullet in his back that never came.The increasing frequency of such incidents in the factory and the evil his eyes had seen at the Pfaszow camp probably were responsible for moving Schindler into a more active antifascist role. In the spring of 1943, he stopped worrying about the production of enamelware appliances for Wehrmacht barracks and began the conspiring, the string-pulling, the bribery, and the shrewd outguessing of Nazi officialdom that finally were to save so many lives. It is at this point that the real legend begins. For the next two years, Oskar Schindler\'s ever-present obsession was how to save the greatest number of Jews from the Auschwitz gas chamber only sixty kilometres from Cracow.His first ambitious move was to attempt to help the starving, fearful prisoners at Plaszow. Other labour camps in Poland, such as Treblinka and Majdanek, had already been shut down and their inhabitants liquidated. Plaszow seemed doomed. At the prompting of Stern and the others in the \"inner-office\" circle, Schindler one evening managed to convince one of his drinking companions, General Schindler--no relative, but well placed as the chief of the war-equipment command in Poland--that Plaszow s camp workshops would be ideally suited for serious war production. At that time they were being used only for the repair of uniforms. The general fell in with the idea and orders for wood and metal were given to the camp. As a result, Plaszow was officially transformed into a war-essential \"concentration camp.\" And though conditions hardly improved, it came off the list of labour camps that were then being done away with. Temporarily at least, Auschwitz\'s fires were cheated of more fuel.The move also put Schindler in well with Plazow\'s commander, the Hauptsturmfuhrer Amon Goeth, who, with the change, now found his status elevated to a new dignity. When Schindler requested that those Jews who continued to work in his factory be moved into their own sub-camp near the plant \"to save time in getting to the job,\" Goeth complied. From then on, Schindler found that be could have food and medicine smuggled into the barracks with little danger. The guards, of course, were bribed, and Goeth never was to discover the true motives in Schindler\'s request.Schindler began to take bigger risks. Interceding for Jews who were denounced for one \"crime\" or another was a dangerous habit in fascist eyes, but Schindler now started to do this almost regularly. \"Stop killing my good workers,\" was his usual technique. \"We\'ve got a war to win. These things can always be settled later.\" The ruse succeeded often enough to save dozens of lives.One August morning in 1943, Schindler played host to two surprise visitors who had been sent to him by the underground organization that the American Jewish welfare agency, the Joint Distribution Committee, then operated in occupied Europe. Satisfied that the men indeed had been sent by Dr. Rudolph Kastner, head of the secret JDC apparatus, who was at the time leading a shadowy existence in Budapest with a sizable price on his head, Schindler called for Stern. \"Speak frankly to these men, Stern,\" he said. \"Let them know what has been going on in Plaszow.\"\"We want a full report on the anti-Semitic persecutions,\" the visitors told Stern. \"Write us a comprehensive report.\"\"Go ahead, urged Schindler. \"They are Swiss. It is safe. You can rely on them. Sit down and write.\"To Stern the risk was purposeless and foolhardy, and he flared up. Turning angrily to Schindler, he asked, \"Schindler, tell me frankly, isn\'t this a provocation? It is most suspicious.\"Schindler in turn became angry at Stem\'s sudden mistrust. \"Write!\" he ordered. Stern had little choice. He wrote everything he could think of, mentioned names of those living and those dead, and penned the long letter that, years later, he discovered had been circulated widely and helped to settle uncertainties in the hearts of the prisoners\' relatives scattered around the world outside Europe. And when the underground subsequently brought him answering letters from America and Palestine, any doubts he still might have had of the integrity or judgment of Oskar Schindler vanished.Life in the Schindler factory went on.Some of the less hardy men and women died, but the majority continued doggedly at their machines, turning out enamelware for the German army. Schindler and his \"inner-office\" circle had become taut and apprehensive, wondering just how long they could continue their game of deception. Schindler himself still entertained the local officers but, with the change of tide that followed Stalingrad and the invasion of Italy, tempers were often out of control. A stroke of a pen could send the Jewish workers to Auschwitz and Schindler along with them. The group moved cautiously, increased the bribes to the guards at the camp and the factory, and, with Schindler\'s smuggled food and medicines, fought for survival. The year 1943 became 1944. Daily, life ended for thousands of Polish Jews. But the Schindlerjuden, to their own surprise, found themselves still alive.By the spring of 1944, the German retreat on the Eastern Front was on in earnest. Plaszow and all its sub-camps were ordered emptied. Schindler and his workers had no illusions about what a move to another concentration camp implied. The time had come for Oskar Schindler to play his trump card, a daring gamble that he had devised beforehand.He went to work on all his drinking companions, on his connections in military and industrial circles in Cracow and in Warsaw. He bribed, cajoled, pleaded, working desperately against time and fighting what everyone assured him was a lost cause. He got on a train and saw people in Berlin. And he persisted until someone, somewhere in the hierarchy, perhaps impatient to end the seemingly trifling business, finally gave him the authorization to move a force of 700 men and 300 women from the Plaszow camp into a factory at Brnenec in his native Sudetenland. Most of the other 25,000 men, women, and children at Plaszow were sent to Auschwitz, there to find the same end that several million other Jews had already discovered. But out of the vast calamity, and through the stubborn efforts of one man, a thousand Jews were saved temporarily. One thousand half-starved, sick, and almost broken human beings had had a death sentence commuted by a miraculous reprieve.The move from the Polish factory to the new quarters in Czechoslovakia, it turned out, was not uneventful. One lot of a hundred did go out directly in July, 1944, and arrived at Brnenec safely. Others, however, found their train diverted without warning to the concentration camp of Gross-Rosen, where many were beaten and tortured and where all were forced to stand in even files in the great courtyard, doing absolutely nothing but putting on and taking off their caps in unison all day long. At length Schindler once more proved successful at pulling strings. By early November all of the Schindlerjuden were again united in their new camp.And until liberation in the spring of 1945 they continued to outwit the Nazis at the dangerous game of remaining alive. Ostensibly the new factory was producing parts for V2 bombs, but, actually, the output during those ten months between July and May was absolutely nil.Jews escaping from the transports then evacuating Auschwitz and the other easternmost camps ahead of the oncoming Russians found haven with no questions asked. Schindler even brazenly requested the Gestapo to send him all intercepted Jewish fugitives: \"in the interest,\" he said, \"of continued war production.\" A hundred additional people were saved in this way, including Jews from Belgium, Holland, and Hungary. \"His children\" reached the number of 1,098: 801 men and 297 women.The Schindlerjuden by now depended on him completely and were fearful in his absence. His compassion and sacrifice were unstinting. He spent every bit of money still left in his possession, and traded his wife\'s jewellery as well, for food, clothing, and medicine, and for schnapps with which to bribe the many SS investigators. He furnished a secret hospital with stolen and black-market medical equipment, fought epidemics, and once made a 300-mile trip himself carrying two enormous flasks filled with Polish vodka and bringing them back full of desperately needed medicine. His wife, Emilie, cooked and cared for the sick and earned her own reputation and praise.In the factory some of the men began turning out false rubber stamps, military travel documents, and the special official papers needed to protect the delivery of food bought illicitly. Nazi uniforms and guns were collected and hidden, along with ammunition and hand grenades, as all eventualities were prepared for. The risks mounted and the tension grew. Schindler, however, seems to have maintained an equilibrium throughout this period that was virtually unshakable. \"Perhaps I had become fatalistic,\" he says now. \"Or perhaps I was just afraid of the danger that would come once the men began to lose hope and acted rashly. I had to keep them full of optimism.\"But two real frights did disturb his normal calm during the constant perils of these months. The first was when a group of workers, lost for some means of expressing their pent-up gratitude, foolishly told him that they had heard the illegal radio broadcast a promise to name a street in postwar Palestine \"Oskar Schindler Strasse.\" For days he waited for the Gestapo to come around. When the hoax was finally admitted he could no longer laugh.The other occurred during a visit from the local SS commandant. As was customary, the SS officer sat around Schindler\'s office drinking glass after glass of vodka and getting drunk rapidly. When he lurched perilously near an iron staircase leading to the basement, Schindler, suddenly yielding to temptation, made one of his rare unpremeditated acts. A slight push, a howl, and a dull thud from the bottom. But the man was not dead. Climbing back into the room with blood pouring from his scalp, he bellowed that Schindler had shot him. Cursing with rage, he flung over his shoulder as he ran out: \"You will not live until any liberation, Schindler. Don\'t think you fool us. You belong in a concentration camp yourself, along with all your Jews!\"SCHINDLER understood \"his children\" and catered to their fears. Near the factory he had been given a beautifully furnished villa that overlooked the length of the valley where the small Czech village lay. But since the workers always dreaded the SS visits that might come late at night and spell their end, Oskar and Emilie Schindler never spent a single night at the villa, sleeping instead in a small room in the factory itselfWhen the Jewish workers died they were secretly buried with full rites despite Nazi rulings that their corpses be burned. Religious holidays were observed clandestinely and celebrated with extra rations of black-market food.Perhaps the most absorbing of all the legends that Schindlerjuden on four continents repeat is one that graphically illustrates Schindler\'s self-adopted role of protector and saviour in the midst of general and amoral indifference. Just about the time the Nazi empire was crashing down, a phone call from the railway station late one evening asked Schindler whether he cared to accept delivery of two railway cars fall of near-frozen Jews. The cars had been frozen shut at a temperature of 5 F and contained almost a hundred sick men who had been locked inside for ten days, ever since the train had been sent off from Auschwitz ten days earlier with orders to deliver the human cargo to some willing factory. But, when informed of the condition of the prisoners, no factory manager would hear of receiving them. \"We are not running a sanatorium!\" was the usual word. Schindler, sickened by the news, ordered the train sent to his factory siding at once.The train was awesome to behold. Ice had formed on the locks and the cars had to be opened with axes and acetylene torches. Inside, the miserable relics of human beings were stretched out, frozen stiff. Each had to be carried out like a carcass of frozen beef. Thirteen were unmistakably dead, but the others still breathed.Throughout that night and for many days and nights following, Oskar and Emilie Schindler and a number of the then worked without halt on the frozen and starved skeletons. One large room in the factory was emptied for the purpose. Three more men died, but with the care, the warmth, the milk, and the medicine, the others gradually rallied. All this had been achieved surreptitiously, with the factory guards, as usual, receiving their bribes so as not to inform the SS commandant. The men\'s convalescence also had to be effected secretly lest they be shot as useless invalids. Later they became part of the factory labour force and joined the others in the motions of feigning war production.Such was life at Brnenec until the arrival of the victorious Russians on May 9 put an end to the constant nightmare. The day before, Schindler had decided that they would have to get rid of the local SS commander just in case he suddenly remembered his drunken threat and got any desperate last-minute ideas. The task was not difficult, for the guards had already begun pouring out of town in panic. Unearthing their hidden weapons, a group slipped out of the factory late at night, found the SS officer drinking himself into oblivion in his room, and shot him from outside his window. In the early morning, once certain that his workers finally were out of danger and that all was in order to explain to the Russians, Schindler, Emilie, and several of his closest friends among the Jewish workers discreetly disappeared and were not heard from until they turned up, months later, deep in Austria\'s U.S. Zone. For the Nazis, he had known all the answers. But at the end he had decided that, as an owner of a German slave-labour factory, he would take no chances on Russian troops casually shooting him before asking for character references or his particular views on the fascist system.IN THE four years that followed, the Schindlerjuden regained their health and scattered to many countries. Some joined relatives in America, others found their way, legally or illegally, to Israel, France, and South America. A majority returned to Poland, but many of these drifted out again and began the life of Displaced Persons (DPs) in Germany\'s many UNRRA camps. Most inevitably lost touch with their good friend Oskar Schindler.For him, everyday life became difficult and unsettled. A Sudeten German, he had no future in Czechoslovakia and at the same time could no longer stand the Germany he had once loved. For a time he tried living in Regensburg. Later he moved to Munich, depending heavily on Care parcels sent him from America by some of the Schindlerjuden, but too proud to plead for more help. Polish Jewish welfare organizations traced him, discovered him in want, and tried to bring some assistance even in the midst of all their own bitter postwar troubles. Ultimately the problem of effecting some sort of recompense was passed on to the Joint Distribution Committee.He began to receive a full JDC ration of food and cigarettes, living like any Jewish DP in the country and being kept alive while a better solution was sought. He became as anti-German in his sentiments as any of the Jewish DPs who now became his only friends. And he proved useful to American authorities, and brought a heap of dangerous hostility upon his own head, by presenting the occupying power with the most detailed documentation on all his old drinking companions, on the vicious owners of the other slave factories that had stood near his, on all the rotten group he had wined and flattered while inwardly loathing in order to save the lives of helpless people.Such is the Schindler story that a thousand people in many different countries today tell. The baffling question that remains is what actually made Oskar Schindler tick. It is doubtful whether any of the Schindlerjuden have yet discovered the real answer. One of them guesses that he was motivated largely by guilt, since it seems a safe assumption that, in order to have earned himself a factory in Poland and the trust of the Nazis, he must have been a member--perhaps an important one--of the Sudeten German Party, Czechoslovakia\'s prewar fascist movement. Another agrees with this hypothesis but refines it on the strength of a rumour. Schindler first parted company with the Nazis, says this theorist, when a young, hot-headed German storm trooper entered his house and savagely struck his wife, Emilie, in front of him during the 1938 march into the Sudetenland.Inquiries in Czechoslovakia have produced many who knew him but more confusion than elucidation. One witness, Ifo Zwicker, not only was among the Jews whom Schindler saved but by a happy coincidence had lived for years in Zwittau, Schindler\'s birthplace and home town. Yet, after enthusiastically confirming the now familiar Schindler saga, Zwicker could only add, uncertainty: \"As a Zwittau citizen I never would have considered him capable of all these wonderful deeds. Before the war, you know, everyone here called him Gauner [swindler or sharper].\" But was the Gauner so disingenuous that he had become an antifascist because he knew the Nazis were doomed? Hardly the answer to explain a conversion in 1939 or 1940, or to account for a hundred serious risks of quick death.The only possible conclusion seems that Oskar Schindler\'s exceptional deeds stemmed from just that elementary sense of decency and humanity that our sophisticated age seldom sincerely believes in. A repentant opportunist saw the light and rebelled against the sadism and vile criminality all around him. The inference may be disappointingly simple, especially for all amateur psychoanalysts who would prefer the deeper and more mysterious motive that may, it is true, still lie unprobed and unappreciated. But an hour with Oskar Schindler encourages belief in the simple answer.Today, at forty, Schindler is a man of convincing honesty and outstanding charm. Tall and erect, with broad shoulders and a powerful trunk, he usually has a cheerful smile on his strong face. His frank, greyblue eyes smile too, except when they tighten in distress as he talks of the past. Then his whole jaw juts out belligerently and his great fists are clutched and pounded in slow anger. When he laughs, it is a boyish and hearty laugh, one that all his listeners enjoy to the full. \"It\'s the personality more than anything else that saved us,\" one of the group once remarked.A few months ago, the continuous efforts being made by many people on his behalf finally bore fruit. After years of trying, the JDC received authorization for his permanent exit from Germany. The organization then presented him with a cash grant, a visa for Argentina, and a boat ticket, and helped him bring to an end the drifting confusion and poverty of the postwar years. Oskar and Emilie Schindler will board a boat in Genoa and sail towards their unknown future. Many of \"his children\" wait in South America to greet them. Emilie Schindler, nee Pelzl, was born on October 22, 1907, in a town called Alt Moletein, a German-speaking town in the Sudetenland, an area of Czechoslovakia inhabited by Germans. After many years of schooling in a convent, Emilie enrolled in agricultural school. Unlike the restrictions of the convent, agricultural school was a place where Emilie thrived. It was a place where she made many friends, including a Jewish girl named Rita Gross. Unlike Oskar (Schindler) whose association with Jews was superficial, Rita Gross and Emilie’s friendship was deep and long lasting. The early years of the twentieth century were fraught with anti-Semitism, however these two girls formed a bond that transcended the sentiment that surrounded them. Their friendship lasted until the beginning of World War II, when in 1942 Rita became a victim of Nazi brutality. Emilie first met Oskar Schindler in 1928, when he approached her home as a traveling salesman selling electric motors. They courted for six weeks and were married on March 6, 1928. Their marriage was difficult right from the beginning, as Oskar’s values and traits were opposite of those held by Emilie. He was a liar, a philanderer, and spent money frivolously, yet he was also was kind, generous and repentant. Oskar eventually bought a large estate in Zwittau, his hometown. At the same time Hitler’s deadly grasp was engulfing Europe.Throughout the early 1930s Schindler worked as a spy for the German Counterintelligence Committee established in Czechoslovakia. During this time Emilie worked for Oskar as an assistant, quietly watching as officers of the Reich paraded through their home. When Poland was invaded in 1939, business opportunities opened for friends of the Reich as black-market goods flowed and Jewish businesses were stripped from their owners. Given this information by his Nazi cohorts, Schindler left Emilie in Zwittau and made his way to Krakow to take advantage of the disruption of Polish life. Eventually, the opportunity to take control of the Jewish-owned enamel-goods factory presented itself. The factory was located close to the Jewish ghetto making it convenient for Schindler to use Jewish workers as cheap labor.Krakow became a seat of the Nazi government and their wanton brutality escalated, laying a path for the annihilation of the Jews of Europe. Schindler’s view of his Jewish workers changed as the horror grew. The Jews were no longer just cheap labor, they were people whose lives were being threatened. At this point Emilie and Oskar decided to risk everything. Their bravery and dedication saved 1,200 people.

Emilie Schindler with women who were saved by her husband, Oskar Schindler. (Argentina) Photo Credit: Yad VashemEmilie Schindler with women who were saved by her husband, Oskar Schindler. (Argentina)