|

On eBay Now...

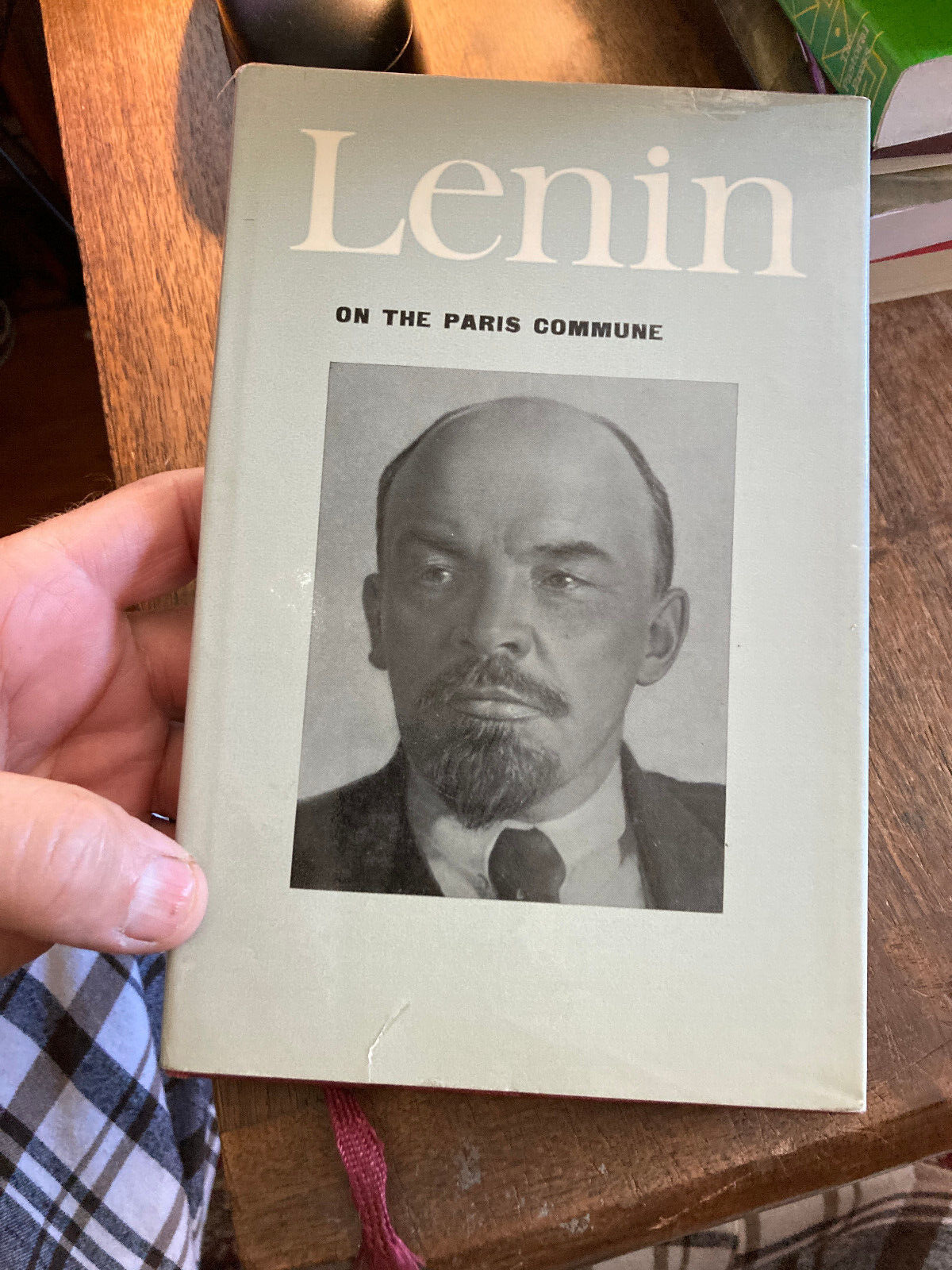

Lenin On The Paris Commune Book 1970 Progress Publishers Communist USSR For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

Lenin On The Paris Commune Book 1970 Progress Publishers Communist USSR:

$14.40

Book is very good, like new aside from former owner\'s name in ink on ffep; DJ is VG++ with one small tape repair. FREE SHIPPING

WIKIPEDIA:

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov[b] (22 April [O.S. 10 April] 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,[c] was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until his death in 1924, and of the Soviet Union from 1922 to 1924. Under his administration, Russia, and later the Soviet Union, became a one-party socialist state governed by the Communist Party. Ideologically a Marxist, his developments to the ideology are called Leninism. Born into an upper-middle-class family in Simbirsk, Lenin embraced revolutionary socialist politics following his brother\'s 1887 execution. Expelled from Kazan Imperial University for participating in protests against the Tsarist government, he devoted the following years to a law degree. He relocated to Saint Petersburg in 1893 where he became a senior Marxist activist. In 1897, he was arrested for sedition and exiled to Shushenskoye in Siberia—where he married Nadezhda Krupskaya—for three years. After his exile, he moved to Western Europe, where he became a prominent theorist in the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP). In 1903, he took a key role in the RSDLP ideological split, leading the Bolshevik faction against Julius Martov\'s Mensheviks. Following Russia\'s failed Revolution of 1905, he initially campaigned for the First World War to be transformed into a Europe-wide proletarian revolution, which, as a Marxist, he believed would cause the overthrow of capitalism and the rise of socialism. After the 1917 February Revolution ousted the Tsar and established a Provisional Government, he returned to Russia and played a leading role in the October Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks overthrew the new government. Lenin\'s Bolshevik government initially shared power with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries, elected soviets, and a multi-party Constituent Assembly, although by 1918 it had centralised power in the new Communist Party. Lenin\'s administration redistributed land among the peasantry and nationalised banks and large-scale industry. It withdrew from the First World War by signing a treaty conceding territory to the Central Powers and promoted world revolution through the Communist International. Opponents were suppressed in the Red Terror, and tens of thousands were killed or interned in concentration camps. His administration defeated right and left-wing anti-Bolshevik armies in the Russian Civil War from 1917 to 1922 and oversaw the Polish–Soviet War of 1919–1921. Responding to wartime devastation, famine and popular uprisings, Lenin encouraged economic growth through the New Economic Policy in 1921. Several non-Russian nations had secured independence from Russia after 1917, but five were forcibly re-united into the new Soviet Union in 1922, while others repelled Soviet invasions. His health failing, Lenin died in Gorki, with Joseph Stalin succeeding him as the pre-eminent figure in the Soviet government. Widely considered one of the most significant and influential figures of the 20th century, Lenin was the posthumous subject of a pervasive personality cult within the Soviet Union until its dissolution in 1991. He became an ideological figurehead behind Marxism–Leninism and a prominent influence over the international communist movement. A controversial and highly divisive historical figure, Lenin is viewed by his supporters as a champion of socialism, communism, anti-imperialism and the working class, while his critics accuse him of establishing a totalitarian dictatorship that oversaw mass killings and political repression of dissidents. Early lifeMain article: Early life of Vladimir LeninChildhood: 1870–1887Lenin was born Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov in Streletskaya Ulitsa, Simbirsk, now Ulyanovsk, on 22 April 1870, and baptised six days later;[2] as a child, he was known as Volodya the common nickname variant of Vladimir.[3] He was the third of eight children, having two older siblings, Anna (born 1864) and Alexander (born 1866). They were followed by three more children, Olga (born 1871), Dmitry (born 1874), and Maria (born 1878). Two later siblings died in infancy.[4] His father, Ilya Nikolayevich Ulyanov, was a devout member of the Russian Orthodox Church and baptised his children into it, although his mother, Maria Alexandrovna Ulyanova (née Blank), a Lutheran by upbringing, was largely indifferent to Christianity, a view that influenced her children.[5] Lenin\'s childhood home in Simbirsk (pictured in 2009)Ilya Ulyanov was from a family of former serfs; Ilya\'s father\'s ethnicity remains unclear, with suggestions that he was of Russian, Chuvash, Mordvin, or Kalmyk ancestry.[6] Despite a lower-class background, he had risen to middle-class status, studying physics and mathematics at Kazan University before teaching at the Penza Institute for the Nobility.[7] In mid-1863, Ilya married Maria,[8] the well-educated daughter of a wealthy Swedish Lutheran mother, and a Russian Jewish father who had converted to Christianity and worked as a physician.[9] According to historian Petrovsky-Shtern, it is likely that Lenin was unaware of his mother\'s half-Jewish ancestry, which was only discovered by Anna after his death.[10] Soon after their wedding, Ilya obtained a job in Nizhny Novgorod, rising to become Director of Primary Schools in the Simbirsk district six years later. Five years after that, he was promoted to Director of Public Schools for the province, overseeing the foundation of over 450 schools as a part of the government\'s plans for modernisation. In January 1882, his dedication to education earned him the Order of Saint Vladimir, which bestowed on him the status of hereditary nobleman.[11] Lenin (left) at the age of three with his sister, OlgaBoth of Lenin\'s parents were monarchists and liberal conservatives, being committed to the emancipation reform of 1861 introduced by the reformist Tsar Alexander II; they avoided political radicals and there is no evidence that the police ever put them under surveillance for subversive thought.[12] Every summer they holidayed at a rural manor in Kokushkino.[13] Among his siblings, Lenin was closest to his sister Olga, whom he often bossed around; he had an extremely competitive nature and could be destructive, but usually admitted his misbehaviour.[14] A keen sportsman, he spent much of his free time outdoors or playing chess, and excelled at school, the disciplinarian and conservative Simbirsk Classical Gymnasium.[15] In January 1886, when Lenin was 15, his father died of a brain haemorrhage.[16] Subsequently, his behaviour became erratic and confrontational, and he renounced his belief in God.[17] At the time, Lenin\'s elder brother Alexander, whom he affectionately knew as Sasha, was studying at Saint Petersburg University. Involved in political agitation against the absolute monarchy of the reactionary Tsar Alexander III, Alexander studied the writings of banned leftists and organised anti-government protests. He joined a revolutionary cell bent on assassinating the Tsar and was selected to construct a bomb. Before the attack could take place, the conspirators were arrested and tried, and Alexander was executed by hanging in May 1887.[18] Despite the emotional trauma of his father\'s and brother\'s deaths, Lenin continued studying, graduated from school at the top of his class with a gold medal for exceptional performance, and decided to study law at Kazan University.[19] University and political radicalisation: 1887–1893Lenin c. 1887Upon entering Kazan University in August 1887, Lenin moved into a nearby flat.[20] There, he joined a zemlyachestvo, a form of university society that represented the men of a particular region.[21] This group elected him as its representative to the university\'s zemlyachestvo council, and he took part in a December demonstration against government restrictions that banned student societies. The police arrested Lenin and accused him of being a ringleader in the demonstration; he was expelled from the university, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs exiled him to his family\'s Kokushkino estate.[22] There, he read voraciously, becoming enamoured with Nikolay Chernyshevsky\'s 1863 pro-revolutionary novel What Is to Be Done?[23] Lenin\'s mother was concerned by her son\'s radicalisation, and was instrumental in convincing the Interior Ministry to allow him to return to the city of Kazan, but not the university.[24] On his return, he joined Nikolai Fedoseev\'s revolutionary circle, through which he discovered Karl Marx\'s 1867 book Capital. This sparked his interest in Marxism, a socio-political theory that argued that society developed in stages, that this development resulted from class struggle, and that capitalist society would ultimately give way to socialist society and then communist society.[25] Wary of his political views, Lenin\'s mother bought a country estate in Alakaevka village, Samara Oblast, in the hope that her son would turn his attention to agriculture. He had little interest in farm management, and his mother soon sold the land, keeping the house as a summer home.[26] Lenin was influenced by the works of Karl Marx.In September 1889, the Ulyanov family moved to the city of Samara, where Lenin joined Alexei Sklyarenko\'s socialist discussion circle.[27] There, Lenin fully embraced Marxism and produced a Russian language translation of Marx and Friedrich Engels\'s 1848 political pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto.[28] He began to read the works of the Russian Marxist Georgi Plekhanov, agreeing with Plekhanov\'s argument that Russia was moving from feudalism to capitalism and so socialism would be implemented by the proletariat, or urban working class, rather than the peasantry.[29] This Marxist perspective contrasted with the view of the agrarian-socialist Narodnik movement, which held that the peasantry could establish socialism in Russia by forming peasant communes, thereby bypassing capitalism. This Narodnik view developed in the 1860s with the People\'s Freedom Party and was then dominant within the Russian revolutionary movement.[30] Lenin rejected the premise of the agrarian-socialist argument but was influenced by agrarian-socialists like Pyotr Tkachev and Sergei Nechaev and befriended several Narodniks.[31] In May 1890, Maria, who retained societal influence as the widow of a nobleman, persuaded the authorities to allow Lenin to take his exams externally at the University of St Petersburg, where he obtained the equivalent of a first-class degree with honours. The graduation celebrations were marred when his sister Olga died of typhoid.[32] Lenin remained in Samara for several years, working first as a legal assistant for a regional court and then for a local lawyer.[33] He devoted much time to radical politics, remaining active in Sklyarenko\'s group and formulating ideas about how Marxism applied to Russia. Inspired by Plekhanov\'s work, Lenin collected data on Russian society, using it to support a Marxist interpretation of societal development and counter the claims of the Narodniks.[34] He wrote a paper on peasant economics; it was rejected by the liberal journal Russian Thought.[35] Revolutionary activityMain article: Revolutionary activity of Vladimir LeninEarly activism and imprisonment: 1893–1900In late 1893, Lenin moved to Saint Petersburg.[36] There, he worked as a barrister\'s assistant and rose to a senior position in a Marxist revolutionary cell that called itself the Social-Democrats after the Marxist Social Democratic Party of Germany.[37] Championing Marxism within the socialist movement, he encouraged the founding of revolutionary cells in Russia\'s industrial centres.[38] By late 1894, he was leading a Marxist workers\' circle, and meticulously covered his tracks to evade police spies.[39] He began a romantic relationship with Nadezhda \"Nadya\" Krupskaya, a Marxist schoolteacher.[40] He also authored a political tract criticising the Narodnik agrarian-socialists, What the \"Friends of the People\" Are and How They Fight the Social-Democrats; around 200 copies were illegally printed in 1894.[41] Police mugshot of Vladimir Lenin, 1895Hoping to cement connections between his Social-Democrats and Emancipation of Labour, a group of Russian Marxists based in Switzerland, Lenin visited the country to meet group members Plekhanov and Pavel Axelrod.[42] He proceeded to Paris to meet Marx\'s son-in-law Paul Lafargue and to research the Paris Commune of 1871, which he considered an early prototype for a proletarian government.[43] Financed by his mother, he stayed in a Swiss health spa before travelling to Berlin, where he studied for six weeks at the Staatsbibliothek and met the Marxist Wilhelm Liebknecht.[44] Returning to Russia with a stash of illegal revolutionary publications, he travelled to various cities distributing literature to striking workers.[45] While involved in producing a news sheet, Rabochee delo (Workers\' Cause), he was among 40 activists arrested in St. Petersburg and charged with sedition.[46] Lenin (seated centre) with other members of the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, 1897Refused legal representation or bail, Lenin denied all charges against him but remained imprisoned for a year before sentencing.[47] He spent this time theorising and writing. In this work he noted that the rise of industrial capitalism in Russia had caused large numbers of peasants to move to the cities, where they formed a proletariat. From his Marxist perspective, Lenin argued that this Russian proletariat would develop class consciousness, which would in turn lead them to violently overthrow tsarism, the aristocracy, and the bourgeoisie and to establish a proletariat state that would move toward socialism.[48] In February 1897, Lenin was sentenced without trial to three years\' exile in eastern Siberia. He was granted a few days in Saint Petersburg to put his affairs in order and used this time to meet with the Social-Democrats, who had renamed themselves the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class.[49] His journey to eastern Siberia took 11 weeks, for much of which he was accompanied by his mother and sisters. Deemed only a minor threat to the government, he was exiled to Shushenskoye, Minusinsky District, where he was kept under police surveillance; he was nevertheless able to correspond with other revolutionaries, many of whom visited him, and permitted to go on trips to swim in the Yenisei River and to hunt duck and snipe.[50] In May 1898, Nadya joined him in exile, having been arrested in August 1896 for organising a strike. She was initially posted to Ufa, but persuaded the authorities to move her to Shushenskoye, where she and Lenin married on 10 July 1898.[51] Settling into a family life with Nadya\'s mother Elizaveta Vasilyevna, in Shushenskoye the couple translated English socialist literature into Russian.[52] There, Lenin wrote A Protest by Russian Social-Democrats to criticise German Marxist revisionists like Eduard Bernstein who advocated a peaceful, electoral path to socialism.[53] He also finished The Development of Capitalism in Russia (1899), his longest book to date, which criticised the agrarian-socialists and promoted a Marxist analysis of Russian economic development. Published under the pseudonym of Vladimir Ilin, upon publication it received predominantly poor reviews.[54] Munich, London, and Geneva: 1900–1905Lenin in 1900After his exile, Lenin settled in Pskov in early 1900.[55] There, he began raising funds for a newspaper, Iskra (Spark), a new organ of the Russian Marxist party, now calling itself the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).[56] In July 1900, Lenin left Russia for Western Europe; in Switzerland he met other Russian Marxists, and at a Corsier conference they agreed to launch the paper from Munich, where Lenin relocated in September.[57] Containing contributions from prominent European Marxists, Iskra was smuggled into Russia,[58] becoming the country\'s most successful underground publication for 50 years.[59] He first adopted the pseudonym Lenin in December 1901, possibly based on the Siberian River Lena;[60] he often used the fuller pseudonym of N. Lenin, and while the N did not stand for anything, a popular misconception later arose that it represented Nikolai.[61] Under this pseudonym, in 1902 he published his most influential publication to date, the pamphlet What Is to Be Done?, which outlined his thoughts on the need for a vanguard party to lead the proletariat to revolution.[62] Nadya joined Lenin in Munich and became his secretary.[63] They continued their political agitation, as Lenin wrote for Iskra and drafted the RSDLP programme, attacking ideological dissenters and external critics, particularly the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SR),[64] a Narodnik agrarian-socialist group founded in 1901.[65] Despite remaining a Marxist, he accepted the Narodnik view on the revolutionary power of the Russian peasantry, accordingly, penning the 1903 pamphlet To the Village Poor.[66] To evade Bavarian police, Lenin moved to London with Iskra in April 1902,[67] where he befriended fellow Russian-Ukrainian Marxist Leon Trotsky.[68] Lenin fell ill with erysipelas and was unable to take such a leading role on the Iskra editorial board; in his absence, the board moved its base of operations to Geneva.[69] The second RSDLP Congress was held in London in July 1903.[70] At the conference, a schism emerged between Lenin\'s supporters and those of Julius Martov. Martov argued that party members should be able to express themselves independently of the party leadership; Lenin disagreed, emphasising the need for a strong leadership with complete control over the party.[71] Lenin\'s supporters were in the majority, and he termed them the \"majoritarians\" (bol\'sheviki in Russian; Bolsheviks); in response, Martov termed his followers the \"minoritarians\" (men\'sheviki in Russian; Mensheviks).[72] Arguments between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks continued after the conference; the Bolsheviks accused their rivals of being opportunists and reformists who lacked discipline, while the Mensheviks accused Lenin of being a despot and autocrat.[73] Enraged at the Mensheviks, Lenin resigned from the Iskra editorial board and in May 1904 published the anti-Menshevik tract One Step Forward, Two Steps Back.[74] The stress made Lenin ill, and to recuperate he holidayed in Switzerland.[75] The Bolshevik faction grew in strength; by spring 1905, the whole RSDLP Central Committee was Bolshevik,[76] and in December they founded the newspaper Vperyod (Forward).[77] Revolution of 1905 and its aftermath: 1905–1914See also: Tampere conference of 1905In January 1905, the Bloody Sunday massacre of protesters in St. Petersburg sparked a spate of civil unrest in the Russian Empire known as the Revolution of 1905.[78] Lenin urged Bolsheviks to take a greater role in the events, encouraging violent insurrection.[79] In doing so, he adopted SR slogans regarding \"armed insurrection\", \"mass terror\", and \"the expropriation of gentry land\", resulting in Menshevik accusations that he had deviated from orthodox Marxism.[80] In turn, he insisted that the Bolsheviks split completely with the Mensheviks; many Bolsheviks refused, and both groups attended the Third RSDLP Congress, held in London in April 1905.[81] Lenin presented many of his ideas in the pamphlet Two Tactics of Social Democracy in the Democratic Revolution, published in August 1905. Here, he predicted that Russia\'s liberal bourgeoisie would be sated by a transition to constitutional monarchy and thus betray the revolution; instead, he argued that the proletariat would have to build an alliance with the peasantry to overthrow the Tsarist regime and establish the \"provisional revolutionary democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry.\"[82] The uprising has begun. Force against Force. Street fighting is raging, barricades are being thrown up, rifles are cracking, guns are booming. Rivers of blood are flowing, the civil war for freedom is blazing up. Moscow and the South, the Caucasus and Poland are ready to join the proletariat of St. Petersburg. The slogan of the workers has become: Death or Freedom! —Lenin on the Revolution of 1905[83] In response to the revolution of 1905, which had failed to overthrow the government, Tsar Nicholas II accepted a series of liberal reforms in his October Manifesto. In this climate, Lenin felt it safe to return to St. Petersburg.[84] Joining the editorial board of Novaya Zhizn (New Life), a radical legal newspaper run by Maria Andreyeva, he used it to discuss issues facing the RSDLP.[85] He encouraged the party to seek out a much wider membership, and advocated the continual escalation of violent confrontation, believing both to be necessary for a successful revolution.[86] Recognising that membership fees and donations from a few wealthy sympathisers were insufficient to finance the Bolsheviks\' activities, Lenin endorsed the idea of robbing post offices, railway stations, trains, and banks. Under the lead of Leonid Krasin, a group of Bolsheviks began carrying out such criminal actions, the best-known taking place in June 1907, when a group of Bolsheviks acting under the leadership of Joseph Stalin committed an armed robbery of the State Bank in Tiflis, Georgia.[87] Although he briefly supported the idea of reconciliation between Bolsheviks and Mensheviks,[88] Lenin\'s advocacy of violence and robbery was condemned by the Mensheviks at the Fourth RSDLP Congress, held in Stockholm in April 1906.[89] After Lenin escaped to Finland from Russia, he was involved in setting up a Bolshevik Centre in Kuokkala, Grand Duchy of Finland, which was at the time an autonomous state controlled by the Russian Empire, before the Bolsheviks regained dominance of the RSDLP at its Fifth Congress, held in London in May 1907.[90] As the Tsarist government cracked down on opposition, both by disbanding Russia\'s legislative assembly, the Second Duma, and by ordering its secret police, the Okhrana, to arrest revolutionaries, Lenin fled Finland for Switzerland.[91] There, he tried to exchange those banknotes stolen in Tiflis that had identifiable serial numbers on them.[92] Alexander Bogdanov and other prominent Bolsheviks decided to relocate the Bolshevik Centre to Paris; although Lenin disagreed, he moved to the city in December 1908.[93] Lenin disliked Paris, lambasting it as \"a foul hole\", and while there he sued a motorist who knocked him off his bike.[94] Lenin became very critical of Bogdanov\'s view that Russia\'s proletariat had to develop a socialist culture in order to become a successful revolutionary vehicle. Instead, Lenin favoured a vanguard of socialist intelligentsia who would lead the working-classes in revolution. Furthermore, Bogdanov, influenced by Ernst Mach, believed that all concepts of the world were relative, whereas Lenin stuck to the orthodox Marxist view that there was an objective reality independent of human observation.[95] Bogdanov and Lenin holidayed together at Maxim Gorky\'s villa in Capri in April 1908;[96] on returning to Paris, Lenin encouraged a split within the Bolshevik faction between his and Bogdanov\'s followers, accusing the latter of deviating from Marxism.[97] Lenin in 1914In May 1908, Lenin lived briefly in London, where he used the British Museum Reading Room to write Materialism and Empirio-criticism, an attack on what he described as the \"bourgeois-reactionary falsehood\" of Bogdanov\'s relativism.[98] Lenin\'s factionalism began to alienate increasing numbers of Bolsheviks, including his former close supporters Alexei Rykov and Lev Kamenev.[99] The Okhrana exploited his factionalist attitude by sending a spy, Roman Malinovsky, to act as a vocal Lenin supporter within the party. Various Bolsheviks expressed their suspicions about Malinovsky to Lenin, although it is unclear if the latter was aware of the spy\'s duplicity; it is possible that he used Malinovsky to feed false information to the Okhrana.[100] In August 1910, Lenin attended the Eighth Congress of the Second International, an international meeting of socialists, in Copenhagen as the RSDLP\'s representative, following this with a holiday in Stockholm with his mother.[101] With his wife and sisters, he then moved to France, settling first in Bombon and then Paris.[102] Here, he became a close friend to the French Bolshevik Inessa Armand; some biographers suggest that they had an extra-marital affair from 1910 to 1912.[103] Meanwhile, at a Paris meeting in June 1911, the RSDLP Central Committee decided to move their focus of operations back to Russia, ordering the closure of the Bolshevik Centre and its newspaper, Proletari.[104] Seeking to rebuild his influence in the party, Lenin arranged for a party conference to be held in Prague in January 1912, and although 16 of the 18 attendants were Bolsheviks, he was heavily criticised for his factionalist tendencies and failed to boost his status within the party.[105] Moving to Kraków in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, a culturally Polish part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, he used Jagiellonian University\'s library to conduct research.[106] He stayed in close contact with the RSDLP, which was operating in the Russian Empire, convincing the Duma\'s Bolshevik members to split from their parliamentary alliance with the Mensheviks.[107] In January 1913, Stalin, whom Lenin referred to as the \"wonderful Georgian\", visited him, and they discussed the future of non-Russian ethnic groups in the Empire.[108] Due to the ailing health of both Lenin and his wife, they moved to the rural town of Biały Dunajec,[109] before heading to Bern for Nadya to have surgery on her goitre.[110] First World War: 1914–1917The [First World] war is being waged for the division of colonies and the robbery of foreign territory; thieves have fallen out–and to refer to the defeats at a given moment of one of the thieves in order to identify the interests of all thieves with the interests of the nation or the fatherland is an unconscionable bourgeois lie. —Lenin on his interpretation of the First World War[111] Lenin was in Galicia when the First World War broke out.[112] The war pitted the Russian Empire against the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and due to his Russian citizenship, Lenin was arrested and briefly imprisoned until his anti-Tsarist credentials were explained.[113] Lenin and his wife returned to Bern,[114] before relocating to Zürich in February 1916.[115] Lenin was angry that the German Social-Democratic Party was supporting the German war effort, which was a direct contravention of the Second International\'s Stuttgart resolution that socialist parties would oppose the conflict and saw the Second International as defunct.[116] He attended the Zimmerwald Conference in September 1915 and the Kienthal Conference in April 1916,[117] urging socialists across the continent to convert the \"imperialist war\" into a continent-wide \"civil war\" with the proletariat pitted against the bourgeoisie and aristocracy.[118] In July 1916, Lenin\'s mother died, but he was unable to attend her funeral.[119] Her death deeply affected him, and he became depressed, fearing that he too would die before seeing the proletarian revolution.[120] In September 1917, Lenin published Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, which argued that imperialism was a product of monopoly capitalism, as capitalists sought to increase their profits by extending into new territories where wages were lower and raw materials cheaper. He believed that competition and conflict would increase and that war between the imperialist powers would continue until they were overthrown by proletariat revolution and socialism established.[121] He spent much of this time reading the works of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Aristotle, all of whom had been key influences on Marx.[122] This changed Lenin\'s interpretation of Marxism; whereas he once believed that policies could be developed based on predetermined scientific principles, he concluded that the only test of whether a policy was correct was its practice.[123] He still perceived himself as an orthodox Marxist, but he began to diverge from some of Marx\'s predictions about societal development; whereas Marx had believed that a \"bourgeoisie-democratic revolution\" of the middle-classes had to take place before a \"socialist revolution\" of the proletariat, Lenin believed that in Russia the proletariat could overthrow the Tsarist regime without an intermediate revolution.[124] February Revolution and the July Days: 1917Lenin\'s travel route from Zurich to St.Petersburg, named Petrograd at the time, in April 1917, including the ride in a so-called \"sealed train\" through German territoryIn February 1917, the February Revolution broke out in St. Petersburg, renamed Petrograd at the beginning of the First World War, as industrial workers went on strike over food shortages and deteriorating factory conditions. The unrest spread to other parts of Russia, and fearing that he would be violently overthrown, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated. The State Duma took over control of the country, establishing the Russian Provisional Government and converting the Empire into a new Russian Republic.[125] When Lenin learned of this from his base in Switzerland, he celebrated with other dissidents.[126] He decided to return to Russia to take charge of the Bolsheviks but found that most passages into the country were blocked due to the ongoing conflict. He organised a plan with other dissidents to negotiate a passage for them through Germany, with which Russia was then at war. Recognising that these dissidents could cause problems for their Russian enemies, the German government agreed to permit 32 Russian citizens to travel by train through their territory, among them Lenin and his wife.[127] For political reasons, Lenin and the Germans agreed to a cover story that Lenin had travelled by sealed train carriage through German territory, but in fact the train was not truly sealed, and the passengers were allowed to disembark to, for example, spend the night in Frankfurt.[128] The group travelled by train from Zürich to Sassnitz, proceeding by ferry to Trelleborg, Sweden, and from there to the Haparanda–Tornio border crossing and then to Helsinki before taking the final train to Petrograd in disguise.[129] The engine that pulled the train on which Lenin arrived at Petrograd\'s Finland Station in April 1917 was not preserved. So Engine #293, by which Lenin escaped to Finland and then returned to Russia later in the year, serves as the permanent exhibit, installed at a platform on the station.[130]Arriving at Petrograd\'s Finland Station in April, Lenin gave a speech to Bolshevik supporters condemning the Provisional Government and again calling for a continent-wide European proletarian revolution.[131] Over the following days, he spoke at Bolshevik meetings, lambasting those who wanted reconciliation with the Mensheviks and revealing his \"April Theses\", an outline of his plans for the Bolsheviks, which he had written on the journey from Switzerland.[132] He publicly condemned both the Mensheviks and the Social Revolutionaries, who dominated the influential Petrograd Soviet, for supporting the Provisional Government, denouncing them as traitors to socialism. Considering the government to be just as imperialist as the Tsarist regime, he advocated immediate peace with Germany and Austria-Hungary, rule by soviets, the nationalisation of industry and banks, and the state expropriation of land, all with the intention of establishing a proletariat government and pushing toward a socialist society. By contrast, the Mensheviks believed that Russia was insufficiently developed to transition to socialism and accused Lenin of trying to plunge the new Republic into civil war.[133] Over the coming months Lenin campaigned for his policies, attending the meetings of the Bolshevik Central Committee, prolifically writing for the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda, and giving public speeches in Petrograd aimed at converting workers, soldiers, sailors, and peasants to his cause.[134] Sensing growing frustration among Bolshevik supporters, Lenin suggested an armed political demonstration in Petrograd to test the government\'s response.[135] Amid deteriorating health, he left the city to recuperate in the Finnish village of Neivola.[136] The Bolsheviks\' armed demonstration, the July Days, took place while Lenin was away, but upon learning that demonstrators had violently clashed with government forces, he returned to Petrograd and called for calm.[137] Responding to the violence, the government ordered the arrest of Lenin and other prominent Bolsheviks, raiding their offices, and publicly alleging that he was a German agent provocateur.[138] Evading arrest, Lenin hid in a series of Petrograd safe houses.[139] Fearing that he would be killed, Lenin and fellow senior Bolshevik Grigory Zinoviev escaped Petrograd in disguise, relocating to Razliv.[140] There, Lenin began work on the book that became The State and Revolution, an exposition on how he believed the socialist state would develop after the proletariat revolution, and how from then on the state would gradually wither away, leaving a pure communist society.[141] He began arguing for a Bolshevik-led armed insurrection to topple the government, but at a clandestine meeting of the party\'s central committee this idea was rejected.[142] Lenin then headed by train and by foot to Finland, arriving at Helsinki on 10 August, where he hid away in safe houses belonging to Bolshevik sympathisers.[143] October Revolution: 1917Main article: October RevolutionPainting of Lenin in front of the Smolny Institute by Isaak BrodskyIn August 1917, while Lenin was in Finland, General Lavr Kornilov, the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army, sent troops to Petrograd in what appeared to be a military coup attempt against the Provisional Government. Premier Alexander Kerensky turned to the Petrograd Soviet, including its Bolshevik members, for help, allowing the revolutionaries to organise workers as Red Guards to defend the city. The coup petered out before it reached Petrograd, but the events had allowed the Bolsheviks to return to the open political arena.[144] Fearing a counter-revolution from right-wing forces hostile to socialism, the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries who dominated the Petrograd Soviet had been instrumental in pressuring the government to normalise relations with the Bolsheviks.[145] Both the Mensheviks and Socialist-Revolutionaries had lost much popular support because of their affiliation with the Provisional Government and its unpopular continuation of the war. The Bolsheviks capitalised on this, and soon the pro-Bolshevik Marxist Trotsky was elected leader of the Petrograd Soviet.[146] In September, the Bolsheviks gained a majority in the workers\' sections of both the Moscow and Petrograd Soviets.[147] Recognising that the situation was safer for him, Lenin returned to Petrograd.[148] There he attended a meeting of the Bolshevik Central Committee on 10 October, where he again argued that the party should lead an armed insurrection to topple the Provisional Government. This time the argument won with ten votes against two.[149] Critics of the plan, Zinoviev and Kamenev, argued that Russian workers would not support a violent coup against the regime and that there was no clear evidence for Lenin\'s assertion that all of Europe was on the verge of proletarian revolution.[150] The party began plans to organise the offensive, holding a final meeting at the Smolny Institute on 24 October.[151] This was the base of the Military Revolutionary Committee (MRC), an armed militia largely loyal to the Bolsheviks that had been established by the Petrograd Soviet during Kornilov\'s alleged coup.[152] In October, the MRC was ordered to take control of Petrograd\'s key transport, communication, printing and utilities hubs, and did so without bloodshed.[153] Bolsheviks besieged the government in the Winter Palace and overcame it and arrested its ministers after the cruiser Aurora, controlled by Bolshevik seamen, fired a blank shot to signal the start of the revolution.[154] During the insurrection, Lenin gave a speech to the Petrograd Soviet announcing that the Provisional Government had been overthrown.[155] The Bolsheviks declared the formation of a new government, the Council of People\'s Commissars, or Sovnarkom. Lenin initially turned down the leading position of Chairman, suggesting Trotsky for the job, but other Bolsheviks insisted and ultimately Lenin relented.[156] Lenin and other Bolsheviks then attended the Second Congress of Soviets on 26 and 27 October and announced the creation of the new government. Menshevik attendees condemned the illegitimate seizure of power and the risk of civil war.[157] In these early days of the new regime, Lenin avoided talking in Marxist and socialist terms so as not to alienate Russia\'s population, and instead spoke about having a country controlled by the workers.[158][dubious – discuss] Lenin and many other Bolsheviks expected proletariat revolution to sweep across Europe in days or months.[159] Lenin\'s governmentMain article: Government of Vladimir LeninOrganising the Soviet government: 1917–1918The Provisional Government had planned for a Constituent Assembly to be elected in November 1917; against Lenin\'s objections, Sovnarkom agreed for the vote to take place as scheduled.[160] In the constitutional election, the Bolsheviks gained approximately a quarter of the vote, being defeated by the agrarian-focused Socialist-Revolutionaries.[161] Lenin argued that the election was not a fair reflection of the people\'s will, that the electorate had not had time to learn the Bolsheviks\' political programme, and that the candidacy lists had been drawn up before the Left Socialist-Revolutionaries split from the Socialist-Revolutionaries.[162] Nevertheless, the newly elected Russian Constituent Assembly convened in Petrograd in January 1918.[163] Sovnarkom argued that it was counter-revolutionary because it sought to remove power from the soviets, but the Socialist-Revolutionaries and Mensheviks denied this.[164] The Bolsheviks presented the Assembly with a motion that would strip

The Paris Commune (French: Commune de Paris, pronounced [kɔ.myn də pa.ʁi]) was a French revolutionary government that seized power in Paris from 18 March to 28 May 1871. During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71, the French National Guard had defended Paris, and working-class radicalism grew among its soldiers. Following the establishment of the Third Republic in September 1870 (under French chief executive Adolphe Thiers from February 1871) and the complete defeat of the French Army by the Germans by March 1871, soldiers of the National Guard seized control of the city on March 18. They killed two French army generals and refused to accept the authority of the Third Republic, instead attempting to establish an independent government. The Commune governed Paris for two months, establishing policies that tended toward a progressive, anti-religious system of their own self-styled socialism, which was an eclectic mix of many 19th-century schools. These policies included the separation of church and state, self-policing, the remission of rent, the abolition of child labor, and the right of employees to take over an enterprise deserted by its owner. All Roman Catholic churches and schools were closed. Feminist, communist, old style social democracy (a mix of reformism and revolutionism), and anarchist currents, among other socialist types, played important roles in the Commune. The various Communards had little more than two months to achieve their respective goals before the national French Army suppressed the Commune at the end of May during La semaine sanglante (\"The Bloody Week\") beginning on 21 May 1871. The national forces still loyal to the government either killed in battle or executed an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Communards, though one unconfirmed estimate from 1876 put the toll as high as 20,000.[5] In its final days, the Commune executed the Archbishop of Paris, Georges Darboy, and about one hundred hostages, mostly gendarmes and priests. 43,522 Communards were taken prisoner, including 1,054 women. More than half of the prisoners were released immediately. Around 15,000 were tried in court, 13,500 of whom were found guilty, 95 were sentenced to death, 251 to forced labor, and 1,169 to deportation (mostly to New Caledonia). Thousands of other Commune members, including several of the leaders, fled abroad, mostly to England, Belgium and Switzerland. All the surviving prisoners and exiles received pardons in 1880 and could return home, where some resumed political careers.[8] Debates over the policies and outcome of the Commune had significant influence on the ideas of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who described it as the first example of the dictatorship of the proletariat. Engels wrote: \"Of late, the Social-Democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesome terror at the words: Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Well and good, gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat.\"[9] PreludeOn 2 September 1870, France was defeated in the Battle of Sedan, and Emperor Napoleon III was captured. When the news reached Paris the next day, shocked and angry crowds came out into the streets. Empress Eugénie, the acting Regent, fled the city, and the government of the Second Empire swiftly collapsed. Republican and radical deputies of the National Assembly proclaimed the new French Republic, and formed a Government of National Defence with the intention of continuing the war. The Prussian army marched swiftly toward Paris. DemographicsIn 1871, France was deeply divided between the large rural, Catholic, and conservative population of the French countryside and the more republican and radical cities of Paris, Marseille, Lyon and a few others. In the first round of the 1869 parliamentary elections held under the French Empire, 4,438,000 had voted for the Bonapartist candidates supporting Napoleon III, while 3,350,000 had voted for the republicans or the legitimists. In Paris, however, the republican candidates dominated, winning 234,000 votes against 77,000 for the Bonapartists.[10] Of the two million people in Paris in 1869, according to the official census, there were about 500,000 industrial workers, or fifteen percent of all the industrial workers in France, plus another 300,000–400,000 workers in other enterprises. Only about 40,000 were employed in factories and large enterprises; most were employed in small industries in textiles, furniture and construction. There were also 115,000 servants and 45,000 concierges. In addition to the native French population, there were about 100,000 immigrant workers and political refugees, the largest number being from Italy and Poland.[10] During the war and the Siege of Paris, various members of the middle and upper classes departed the city. At the same time, there was an influx of refugees from parts of France occupied by the Germans. The working class and immigrants suffered the most from the lack of industrial activity due to the war and the siege; they formed the bedrock of the Commune\'s popular support.[10] Radicalisation of the Paris workersThe Commune resulted in part from growing discontent among the Paris workers.[11] This discontent can be traced to the first worker uprisings, the Canut revolts (a canut was a Lyonnais silk worker, often working on Jacquard looms), in Lyon and Paris in the 1830s.[12] Many Parisians, especially workers and the lower-middle classes, supported a democratic republic. A specific demand was that Paris should be self-governing with its own elected council, something enjoyed by smaller French towns but denied to Paris by a national government wary of the capital\'s unruly populace. Socialist movements, such as the First International, had been growing in influence with hundreds of societies affiliated to it across France. In early 1867, Parisian employers of bronze-workers attempted to de-unionise their workers. This was defeated by a strike organised by the International. Later in 1867, a public demonstration in Paris was answered by the dissolution of its executive committee and the leadership being fined. Tensions escalated: Internationalists elected a new committee and put forth a more radical programme, the authorities imprisoned their leaders, and a more revolutionary perspective was taken to the International\'s 1868 Brussels Congress. The International had considerable influence even among unaffiliated French workers, particularly in Paris and the large cities.[13] The killing of journalist Victor Noir incensed Parisians, and the arrests of journalists critical of the Emperor did nothing to quiet the city. The German military attaché, Alfred von Waldersee, wrote in his diary in February: \"Every night isolated barricades were thrown up, constructed for the most part out of disused conveyances, especially omnibuses, a few shots were fired at random, and scenes of disorder were taken part in by a few hundreds of persons, mostly quite young\". He noted, however, that \"working-men, as a class, took no part in the proceedings.\"[14] A coup was attempted in early 1870, but tensions eased significantly after the plebiscite in May. The war with Prussia, initiated by Napoleon III in July, was initially met with patriotic fervour.[15] Radicals and revolutionariesLouis Auguste Blanqui, leader of the Commune\'s far-left faction, was imprisoned for the entire time of the Commune.Paris was the traditional home of French radical movements. Revolutionaries had gone into the streets and overthrown their governments during the popular uprisings of July 1830 and the French Revolution of 1848, as well as subsequent failed attempts such as the 1832 June Rebellion and the uprising of June 1848. Of the radical and revolutionary groups in Paris at the time of the Commune, the most conservative were the \"radical republicans\". This group included the young doctor and future prime minister Georges Clemenceau, who was a member of the National Assembly and Mayor of the 18th arrondissement. Clemenceau tried to negotiate a compromise between the Commune and the government, but neither side trusted him; he was considered extremely radical by the provincial deputies of rural France, but too moderate by the leaders of the Commune. The most extreme revolutionaries in Paris were the followers of Louis Auguste Blanqui, a charismatic professional revolutionary who had spent most of his adult life in prison.[16] He had about a thousand followers, many of them armed and organized into cells of ten persons each. Each cell operated independently and was unaware of the members of the other groups, communicating only with their leaders by code. Blanqui had written a manual on revolution, Instructions for an Armed Uprising, to give guidance to his followers. Though their numbers were small, the Blanquists provided many of the most disciplined soldiers and several of the senior leaders of the Commune. Defenders of ParisBy 20 September 1870, the German army had surrounded Paris and was camped just 2,000 metres (6,600ft) from the French front lines. The regular French Army in Paris, under General Trochu\'s command, had only 50,000 professional soldiers of the line; the majority of the French first-line soldiers were prisoners of war, or trapped in Metz, surrounded by the Germans. The regulars were thus supported by around 5,000 firemen, 3,000 gendarmes, and 15,000 sailors.[17] The regulars were also supported by the Garde Mobile, new recruits with little training or experience. 17,000 of them were Parisian, and 73,000 from the provinces. These included twenty battalions of men from Brittany, who spoke little French.[17] The largest armed force in Paris was the National Guard, numbering about 300,000 men. They also had very little training or experience. They were organised by neighbourhoods; those from the upper- and middle-class arrondissements tended to support the national government, while those from the working-class neighbourhoods were far more radical and politicised. Guardsmen from many units were known for their lack of discipline; some units refused to wear uniforms, often refused to obey orders without discussing them, and demanded the right to elect their own officers. The members of the National Guard from working-class neighbourhoods became the main armed force of the Commune.[17] Siege of Paris; first demonstrationsEugène Varlin led several thousand National Guard soldiers to march to the Hôtel de Ville chanting \"Long Live the Commune!\"As the Germans surrounded the city, radical groups saw that the Government of National Defence had few soldiers to defend itself, and launched the first demonstrations against it. On 19 September, National Guard units from the main working-class neighbourhoods—Belleville, Ménilmontant, La Villette, Montrouge, the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and the Faubourg du Temple—marched to the centre of the city and demanded that a new government, a Commune, be elected. They were met by regular army units loyal to the Government of National Defence, and the demonstrators eventually dispersed peacefully. On 5 October, 5,000 protesters marched from Belleville to the Hôtel de Ville, demanding immediate municipal elections and rifles. On 8 October, several thousand soldiers from the National Guard, led by Eugène Varlin of the First International, marched to the centre chanting \'Long Live the Commune!\", but they also dispersed without incident. Later in October, General Louis Jules Trochu launched a series of armed attacks to break the German siege, with heavy losses and no success. The telegraph line connecting Paris with the rest of France had been cut by the Germans on 27 September. On 6 October, Defense Minister Léon Gambetta departed the city by balloon to try to organise national resistance against the Germans.[18] Uprising of 31 OctoberRevolutionary units of the National Guard briefly seized the Hôtel de Ville on 31 October 1870, but the uprising failed.Main article: 1870 Paris uprisingOn 28 October, the news arrived in Paris that the 160,000 soldiers of the French army at Metz, which had been surrounded by the Germans since August, had surrendered. The news arrived the same day of the failure of another attempt by the French army to break the siege of Paris at Le Bourget, with heavy losses. On 31 October, the leaders of the main revolutionary groups in Paris, including Blanqui, Félix Pyat and Louis Charles Delescluze, called new demonstrations at the Hôtel de Ville against General Trochu and the government. Fifteen thousand demonstrators, some of them armed, gathered in front of the Hôtel de Ville in pouring rain, calling for the resignation of Trochu and the proclamation of a commune. Shots were fired from the Hôtel de Ville, one narrowly missing Trochu, and the demonstrators crowded into the building, demanding the creation of a new government, and making lists of its proposed members.[19] Blanqui, the leader of the most radical faction, established his own headquarters at the nearby Prefecture of the Seine, issuing orders and decrees to his followers, intent upon establishing his own government. While the formation of the new government was taking place inside the Hôtel de Ville, however, units of the National Guard and the Garde Mobile loyal to General Trochu arrived and recaptured the building without violence. By three o\'clock, the demonstrators had been given safe passage and left, and the brief uprising was over.[19] On 3 November, city authorities organized a plebiscite of Parisian voters, asking if they had confidence in the Government of National Defence. \"Yes\" votes totalled 557,996, while 62,638 voted \"no\". Two days later, municipal councils in each of the twenty arrondissements of Paris voted to elect mayors; five councils elected radical opposition candidates, including Delescluze and a young Montmartrean doctor, Georges Clemenceau.[20] Negotiations with the Germans; continued warIn September and October, Adolphe Thiers, the leader of the National Assembly conservatives, had toured Europe, consulting with the foreign ministers of Britain, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, and found that none of them were willing to support France against the Germans. He reported to the government that there was no alternative to negotiating an armistice. He travelled to German-occupied Tours and met with Otto von Bismarck on 1 November. The German Chancellor demanded the cession of all of Alsace, parts of Lorraine, and enormous reparations. The Government of National Defence decided to continue the war and raise a new army to fight the Germans. The newly organized French armies won a single victory at Coulmiers on 10 November, but an attempt by General Auguste-Alexandre Ducrot on 29 November at Villiers to break out of Paris was defeated with a loss of 4,000 soldiers, compared with 1,700 German casualties. Everyday life for Parisians became increasingly difficult during the siege. In December, temperatures dropped to −15°C (5°F), and the Seine froze for three weeks. Parisians suffered shortages of food, firewood, coal and medicine. The city was almost completely dark at night. The only communication with the outside world was by balloon, carrier pigeon, or letters packed in iron balls floated down the Seine. Rumours and conspiracy theo

Vintage Rare Pair USSR Lenin on the Stand & to Petrograd Propaganda Prints $750.00

1966 LENIN on the hunt & a man with a gun Hunting ART OLD Russian Postcard USSR $10.90

Lenin On The Paris Commune Book 1970 Progress Publishers Communist USSR $14.40

Vladimir Lenin Autograph Reprint On Genuine Original Period 1917 3X5 Card $5.00

USSR SOVIET PIN BADGE. LENIN ON FLAG. HAMMER AND SICKLE $13.99

Russia V. Lenin 1969 continental size postcard with PS on the back cover $3.99

1982 LENIN On Red Square in Moscow Red Army soldiers Flag OLD Russia Postcard $9.90

oil painting handpainted on canvas "Lenin and Stalin in the summer of 1917" $116.00

|