|

On eBay Now...

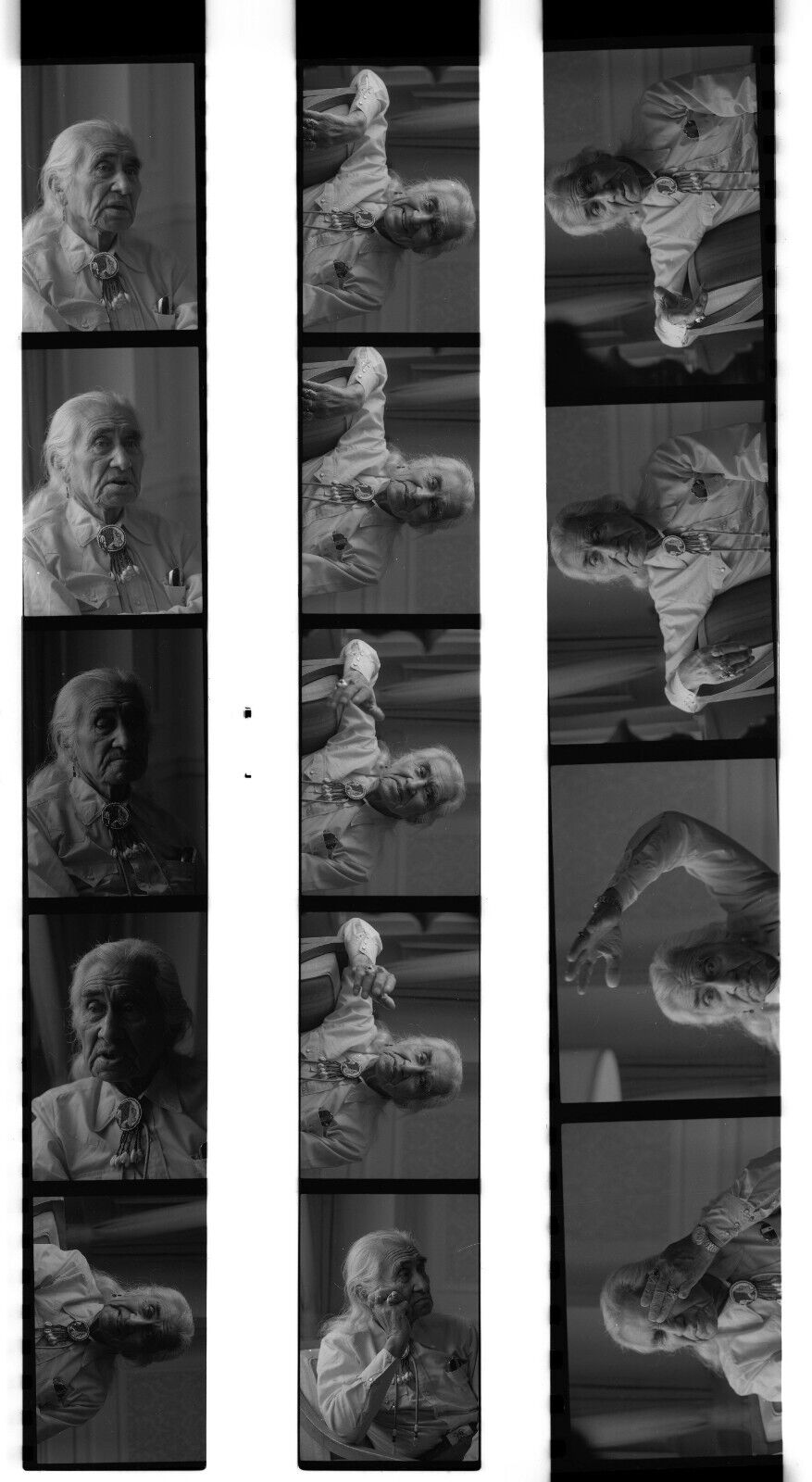

CHIEF DAN GEORGE NEGATIVES SCARCE Tsleil-Waututh Nation FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPHER For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

CHIEF DAN GEORGE NEGATIVES SCARCE Tsleil-Waututh Nation FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPHER:

$300.00

These rare 14 negatives captures the iconic Chief Dan George in his prime, taken by renowned legendary Chicago photographer Manuel Leon Lopez in 1975. The 35mm negatives, unframed and original, are a scarce find for any collector of art, celebrity, or movie memorabilia. The image are a timeless piece of history, perfect for any art lover or fan of the famous actor. Don\'t miss your chance to own this original piece of vintage photography.Chief Dan George OC was a chief of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, a Coast Salish band whose Indian reserve is located on Burrard Inlet in the southeast area of the District of North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. He also was an actor, musician, poet and author. The Chief\'s best-known written work is My Heart Soars. Dan George OC (born Geswanouth Slahoot; July 24, 1899 – September 23, 1981) was a chief of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, a Coast Salish band whose Indian reserve is located on Burrard Inlet in the southeast area of the District of North Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. He also was an actor, musician, poet and author. The Chief\'s best-known written work is My Heart Soars.[1] As an actor, he is best remembered for portraying Old Lodge Skins opposite Dustin Hoffman in Little Big Man (1970), for which he was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, and for his role in The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976), as Lone Watie, opposite Clint Eastwood.

Early yearsBorn as Geswanouth Slahoot in North Vancouver,[2] his English name was originally Dan Slaholt. The surname was changed to George when he entered a residential school at age 5.[2] He worked at a number of different jobs, including as a longshoreman, construction worker, and school bus driver,[3] and was band chief of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation from 1951 to 1963 (then called the Burrard Indian Band).[4]

Acting career

1960–1970: Early roles and breakthroughIn 1960, when he was already 60 years old, he landed his first acting job in a CBC Television series, Cariboo Country, as the character Ol\' Antoine (pron. \"Antwine\"). He performed the same role in a Walt Disney Studios film Smith! (1969),[5] adapted from an episode in the series The High Chaparral (the episode in turn being based on Breaking Smith\'s Quarter Horse, a novella by Paul St. Pierre).In 1970, at age 71, he received several honours for his role in Arthur Penn\'s film Little Big Man, including a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.[3][6][7]

1971–1981: Subsequent successIn 1971 He played Chief Red Cloud in Season 13 Episode 14 (Warbonnet) on the Western series Bonanza. He played the role of Rita Joe\'s father in George Ryga\'s stage play, The Ecstasy of Rita Joe, in performances at Vancouver, the National Arts Centre in Ottawa, and Washington, D.C.In 1972, he was among the guests in David Winters\'s television special The Special London Bridge Special.[8] That same year he acted in the film Paul Bogart\'s Cancel My Reservation,[9] and got the recurring role of Chief Moses Charlie in the comedy-drama television series The Beachcombers, a role he would revisit until his death in 1981.In 1973, he played the role of \"Ancient Warrior\" in an episode of the TV show Kung Fu. That same year George recorded \"My Blue Heaven\" with the band Fireweed,[10] with \"Indian Prayer\" on the reverse. His album, Chief Dan George & Fireweed – In Circle, was released in 1974 comprising these songs and seven others.[11]The following year he had roles in Alien Thunder (1974),[12] The Bears and I (1974),[13] and Harry and Tonto (1974).[14]In 1975, he portrayed the character Chief Stillwater in the \"Showdown at Times Square\" episode in Season 6 of McCloud.

Dan George with Sondra Locke and Clint Eastwood at a barbecue in Santa Fe, New Mexico, promoting The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976).In 1976 he acted in Clint Eastwood\'s The Outlaw Josey Wales,[15] and George McCowan\'s Shadow of the Hawk.[16]On television the following year he had a role in the 1978 miniseries Centennial, based on the book by James A. Michener.In 1979, he acted in Americathon,[17] and Spirit of the Wind.[18]In 1980 he had his final film role in Nothing Personal.[19]

1984: Posthumous written workGeorge was well known for his poetic writing style and in 1974, George wrote My Heart Soars followed by My Spirit Soars in 1983, both published by Hancock House Publishers. The two books were later combined to form The Best of Chief Dan George which went on to become a best seller and continues to sell well today. One of his better known pieces of poetry A Lament for Confederation has become one of his most widely known works.

DeathThe Chief died at Lions Gate Hospital in North Vancouver in 1981 at the age of 82.[20] He was interred at Burrard Cemetery.

Personal lifeDan George\'s granddaughter Lee Maracle was a poet, author, activist, and professor.[21] His granddaughter Charlene Aleck is an actress who performed for 18 years on The Beachcombers on CBC. His granddaughter Joan Phillip is the BC NDP MLA for Vancouver-Mount Pleasant. His great-granddaughter Columpa Bobb is an actress and poet.Chief Dan George\'s grand-nephew, Chief Jesse \"Nighthawk\" George, currently resides in Chesapeake, Virginia, and is the Inter-Tribal Peace Chief for the Commonwealth of Virginia.

ActivismDuring his acting career, he worked to promote better understanding by non-aboriginals of the First Nations people. His soliloquy, Lament for Confederation,[22] an indictment of the appropriation of native territory by European colonialism, was performed at the City of Vancouver\'s celebration of the Canadian centennial in 1967.[23] This speech is credited with escalating native political activism in Canada and touching off widespread pro-native sentiment among non-natives.[23]

AccoladesChief Dan George received the following accolades for Little Big Man.

Award Category Result

Academy Awards Best Supporting Actor Nominated

Golden Globe Awards Best Supporting Actor

New York Film Critics Circle Awards Best Supporting Actor Won

National Society of Film Critics Awards Best Supporting Actor

Laurel Awards Best Supporting Performance, Male

Honours and legacy

Dan George\'s B.C. Entertainment Hall of Fame star on Granville Street, Vancouver, BCIn 1971, George was made an Officer of the Order of Canada.[24]He was included on the Golden Rule Poster under \"Native Spirituality\" with the quote: \"We are as much alive as we keep the earth alive\".[25]Canadian actor Donald Sutherland narrated the following quote from his poem \"My Heart Soars\" in the opening ceremonies of the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.[26] The beauty of the trees,

the softness of the air,

the fragrance of the grass,

speaks to me.

And my heart soars.Legacy Chief Dan George Middle School in Abbotsford, British Columbia

Chief Dan George Public School in Toronto, Ontario[27]

Chief Dan George Theatre, Phoenix Theatre, University of Victoria, British ColumbiaIn 2008 Canada Post issued a postage stamp in its \"Canadians in Hollywood\" series featuring Chief Dan George.[28]

Filmography

Duration: 21 minutes and 50 seconds.21:50Subtitles available.CC

Man Belongs to the Earth (1974), an IMAX short environmentalist documentary film starring George

Year Title Role Notes

1969 Smith! Ol\' Antoine

1970 Little Big Man Old Lodge Skins

1972 Cancel My Reservation Old Bear

1972 À bon pied, bon oeil

1974 Alien Thunder Sounding Sky

1974 The Bears and I Chief Peter A-Tas-Ka-Nay

1974 Harry and Tonto Sam Two Feathers

1974 Man Belongs to the Earth Himself

1974 Chief Dan George Speaks Himself

1975 Cold Journey

1976 The Outlaw Josey Wales Lone Watie

1976 Shadow of the Hawk Old Man Hawk

1978 Pump It Up

1979 Americathon Sam Birdwater

1979 Spirit of the Wind Moses

1979 The Incredible Hulk Lone Wolf Season 2, Episode 19, \"Kindred Spirits\"

1980 Nothing Personal Oscar

Written works George, Dan, and Helmut Hirnschall. My Heart Soars. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin, 1974. ISBN 0-919654-15-0

George, Dan, and Helmut Hirnschall. My Spirit Soars. Surrey, B.C., Canada: Hancock House, 1982. ISBN 0-88839-154-4

Mortimer, Hilda, and Dan George. You Call Me Chief: Impressions of the Life of Chief Dan George. Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 1981. ISBN 0-385-04806-8

George, Dan, and Helmut Hirnschall. The Best of Chief Dan George. Surrey, B.C.: Hancock House, 2003. ISBN 0-88839-544-2See also Indigenous peoples of the Americas portalflagCanada portalBiography portal Dark Cloud

Chief Thundercloud

Iron Eyes Cody

History of Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh longshoremen, 1863–1963

Indigenous Canadian personalities

Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest CoastManuel León López II, age 87, died January 22, 2023, at Cape Cod Hospital following a brief illness. He had been a resident of Cape Regency nursing facility in Centerville for the past six years. Friends remember him as gentle, kind and highly intelligent man who loved reading (especially about dinosaurs, archaeology and astronomy); classical music (especially Bach); and cinema. (He liked to tell people, quite truthfully, that he had seen Fellini’s surrealistic film “8½” eight and a half times.) A former photo editor for the Cape Cod Times, he also had a great eye for photography.Manuel was born August 22, 1935, in Columbus, Ohio, the son of Alberta (Mettle) López and Manuel León López Sr. Even through college he was known by his nickname, “Coyo,” inspired by a word he chirped as a baby. He would not be all that pleased for this to be public knowledge. Nor was he exactly thrilled if you called him “Manny.”The family moved to Tucson, Arizona, when Manuel was very young. From age nine to 14 he sang soprano with the Tucson Arizona Boys Choir. Founder and director Eduardo Caso promoted the choir as America’s answer to the Vienna Boys Choir and arranged concerts throughout the West as well as several national radio broadcasts. One year they sang at an Easter service at the Grand Canyon, which was broadcast nationally on NBC.Following high school graduation, Manuel attended the University of Arizona, majoring in journalism, minoring in English and history, and working on the college newspaper. He extended his college studies to five years because – always curious – he wanted to take more courses. During these years, he twice had a summer job as acting editor at a weekly paper in the Tucson area—first for the San Manuel Miner and then the Coolidge Examiner.After college graduation, Manuel enlisted in the U.S. Army, receiving his discharge as a buck sergeant. He was stationed in Germany for two and a half years, serving as an agent with the Army’s Counterintelligence Corp, mostly performing background investigations for security clearances but occasionally undertaking a more intriguing, photographically oriented assignment. While in Europe he eagerly took the opportunity to travel to Holland, France, England, Italy and Spain, where he visited his father’s birthplace, Granada.Back in the United States in the early 1960s, Manuel began his career as a photojournalist. His first position was with International Harvester in Chicago, where he shot picture stories for the company’s two magazines—International Harvester Today, an internal publication for employees, and International Harvester World, an external, public relations-oriented vehicle. While there, he worked with Angus McDougall, who went on to become a legend in the field of photojournalism. He was a tough boss, Manuel would say, but he learned a lot from him.Next, Manuel worked for National Geographic in Washington, D.C., for about three and a half years. In his position as director of photography, he was responsible for culling the best images for the magazine, famous for its exceptional photography. While he was there, the magazine also published seven of his own photos. At some point, Manuel also had a stunning picture of a saguaro cactus at sunset published on the back cover of Arizona Highways.Manuel returned to Chicago in the early 1970s, taking a job as staff photographer for the Chicago Daily News for several years. Then McDougall, who had become director of the Photojournalism program at the University of Missouri School of Journalism in Columbia, offered him a teaching position. For the next seven years, Manuel taught Photojournalism at the school and nearly completed the course work toward his own master’s degree in Journalism.In the 1980s, Manuel worked relatively briefly as picture editor for Gannet Westchester Newspaper in Westchester County, New York. Eight or more newspapers were all printed in the same plant, and the position required him to work the graveyard shift. “It was hell,” he recalled.But from there he got his final job at the Cape Cod Times, where then Editor in Chief Bill Breisky hired him as photo editor in 1987 and he worked for 20 years, retiring in 2007. Manuel did a graphic redesign of the paper in the 1990s, pretty much single-handedly. When the Times moved its presses to Independence Park, allowing for the expansion of the newsroom, he strongly and successfully advocated for a larger and top-of-the-line photo studio and darkroom. He moved to a less stressful job as a page designer in the late \'90s but left a lasting impression on Times photographers as well as many others who worked with him.“He was into what he did—it wasn’t just a job for him,” says longtime Times photographer Steve Heaslip. “He really pushed us outside of the envelope. I’m not sure we always wanted it, but we were all better photographers for it.”Though reserved and a bit shy, Manuel always enjoyed a social gathering. He never married and had no surviving family, but he’ll be missed and fondly remembered by those who knew him best, including Steve, Vince DeWitt, Jim Warren, Susan Moeller, Bill Mills and Mary Ellen Evans. But by none more so than his especially close friend, Cindy Nickerson.An informal gathering for the interment of ashes will be held at a later date.Chief Dan George of the Burrard tribe, who was best known for his role in the 1970 movie \'\'Little Big Man,\'\' died today in his sleep at Lions Gate Hospital. He was 82 years old.Chief Dan George was nominated for an Academy Award for his portrayal of Old Lodge Skins in \'\'Little Big Man,\'\' which starred Dustin Hoffman.He was chief of the Burrard tribe from 1951 to 1963, when he turned to an acting career, starring in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television series \'\'Caribou Country.\'\'Besides his successful acting career, Chief Dan George was also known as an eloquent spokesman for native rights and the environment. In 1971 he received the Human Relations award from the Canadian Council of Christians and Jews. Oscar Nomination at 71His Oscar nomination at the age of 71, he said, achieved a goal he set for himself when he took up acting at 62 - \'\'to do something that would give a name to the Indian people.\'\'He said he was impressed by the progress that Indians had made in his lifetime, noting that he himself, as an old man, had become \'\'more forward and bold.\'\' \'\'Some of our people stand and wait and don\'t talk for themselves,\'\' he said, \'\'but this is becoming a thing of the past. The younger Indians consider themselves equal to the white man.\'\'A native of North Vancouver, Dan George was for 12 years chief of the tiny, 200-member, Tell-lall-watt tribe of the Coastsalish nation. He later became honorary chief of the Squamish and Sushwap bands.He was a stevedore until 1947, when a swinging timber smashed into his side, permanently injuring a hip. Chief Dan George said he got into show business because Robert, the oldest of his six children, was playing an Indian in \'\'Caribou Country\'\' when the white actor playing an old Indian fell ill and the director wondered where he could find a replacement. Led to Major Movie Role\'\'Why not try a real old Indian?\'\' Robert asked. \'\'I\'ve got one at home.\'\' Chief Dan George came to the attention of the \'\'Little Big Man\'\' producers when he appeared in \'\'Smith,\'\' a Walt Disney film in which he played an old Indian who wins acquittal for a young Indian charged with murder by reciting the famous speech of the conquered Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, \'\'I shall fight no more forever.\'\'He said he was proud to see Indians who saw that film \'\'walk out of the theater and walk up to a white ma n and shake him by the hand. \'\'That\'s what they\'ve got to do, you know - believe in themselves andtry to fit in .\'\'Chief Dan George was the father of six children, Marie, Ann, Irene, Rose, Leonard and Robert. His wife, Amy, died in 1971, while he was preparing to go to Hollywood for the Oscar ceremonies.Actor. A native of North Vancouver, British Columbia, he was Chief of the Squamish Band of the Salish Indian Tribe of Burrard Inlet, British Columbia, and a highly respected actor of both American actors and Canadian actors. Born \'Geswanouth Slahhot,\' George had also worked as a logger, longshoreman, construction worker, and a school bus driver. In 1960, George began his acting career when he auditioned for the part of \'Old Antoine\' for the television series, \"Cariboo County,\" and won it. George played the role from 1960 to 1967. George then began a long and successful career on both stage, on television, and in films. Among his other projects were the films, \"Smith\" (1969), \"A Bon Pied, Bon Oeil\" (1972), \"The Special London Bridge Special\" (1972), \"Cancel My Reservation\" (1972), \"A Different Drum\" (1974), \"Chief Dan George Speaks\" (1974), \"Alien Thunder\" (1974), \"Harry And Tonto\" (1974), \"The Bears And I\" (1974), \"Cold Journey\" (1975), \"The Outlaw Josey Wales\" (1976), \"Shadow Of The Hawk\" (1976), \"Americathon\" (1979), \"Spirit Of The Wind,\" \"Nothing Personal\" (1980), and his television appearances, \"The Incredible Hulk,\" \"Matt And Jenny,\" \"McCloud,\" \"V.I.P.-Schaukel,\" \"Marcus Welby, M.D.,\" Cade\'s County,\" \"Bonanza,\" \"The High Chaparral,\" \"The Beachcombers,\" and \"Centennial.\" In 1970, George received the nomination of Best Supporting Actor for his role as \'Old Lodge Skins\' in the film, \"Little Big Man.\" George also became a stage actor appearing in the play, \"The Ectasy Of Rita Joe\" in 1967, and also a successful poet writing the books, \"My Heart Soars\" (1974), and \"My Spirit Soars\" (1982). George also recited his famous work, \"Lament For Confederation\" at the Canadian Centennial Celebrations in Vancouver, British Columbia, in 1967, and he also became an influential speaker on the rights of the native peoples of North America. On September 23, 1981, Chief Dan George died in Vancouver, British Columbia, at the age of 82, and was buried at his native birthplace. George was succeeded as Chief by his son.The Tsleil-Waututh Nation (Halkomelem: səlilwətaɬ, IPA: [səlilwətaɬ]), formerly known as the Burrard Indian Band or Burrard Inlet Indian Band, is a First Nations band government in the Canadian province of British Columbia. The Tsleil-Waututh Nation (\"TWN\") are Coast Salish peoples who speak hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓, the Downriver dialect[2] of the Halkomelem language, and are closely related to but politically and culturally separate from the nearby nations of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), with whose traditional territories some claims overlap.The TWN is a member government of the Naut\'sa mawt Tribal Council, which includes other governments on the upper Sunshine Coast, southeastern Vancouver Island and the Tsawwassen band on the other side of the Vancouver metropolis from the Tsleil-Waututh. There are almost 600 members with 287 living on the reserve as of January 2018.[3]According to the 2011 National Community Well-Being Index, Burrard Inlet 3 is considered the most prosperous First Nation community in Canada.[4]

Notable membersThe most famous member of the TWN was Chief Dan George, an actor and native rights advocate best known for his role as Old Lodge Skins in Little Big Man, The Outlaw Josey Wales and for another role as Old Antoine in the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation television series Cariboo Country (based on books by Paul St. Pierre). His descendants still figure prominently in TWN government and culture. The TWN is also known for its war canoe racing team, The Burrard Canoe Club.Hereditary Chief John L. George was the longest serving elected Chief and founding member of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs, formed in 1969 against the Liberal \'White Paper\' Policy that would end Indian status. He was a strong advocate and protector of TWN Aboriginal Rights and Title. Leonard H. George was elected Chief and created the TWN Takaya Developments and began the partnerships that have brought much real estate development to TWN. Leonard also brought TWN into the BC Treaty Process and was a strong voice for the TWN. As well, he is the son of Dan George and was a successful actor as well as a politician.The TWN operates an ocean-going canoe tour/experience known as Takaya Tours

Reserves

Map all coordinates using OpenStreetMapDownload coordinates as:Indian Reserves under the administration of the Squamish Nation are:[5] Burrard Inlet 3 (Halkomelem: səlil̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ), on the north shore of Burrard Inlet, in District of North Vancouver, Main Reserve of the Nation, 108.2 hectares (267 acres). 49.3104485°N 122.98111911°W

Inlailwatash 4, about 1 km (1000 yards) upstream from the mouth of Indian River, 19 km (12 mi) North-Northeast of Burrand Inlet 3 Reserve, 0.5 ha (1+1⁄4 acres). 49.47396602°N 122.8828676498°W

Inlailwatash 4A, about 1.3 km (1500 yards) upstream from mouth of Indian River, 19 km (12 mi) North-Northeast of Burrand Inlet 3 Reserve, 2 hectares (4.9 acres). 49.4761317736°N 122.885185811°WDocumentary and Notable EventsIn 2006, a documentary followed and was filmed by four Tsleil-Waututh youth to highlight their struggles with the education system. The documentary — titled Reds, Whites & the Blues and/or, Reading, Writing & the Rez — is a CBC Newsworld in-house production co-produced with CBUT.In 2010 TWN helped welcome the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics as part of the Four Host First Nations, which included Musqueam, Squamish, and Lil\'wat Nations. It was the first time that Canada accommodated the Indigenous nations interest in the event. It was the first time Indigenous title holders were recognized by the Olympic body.The TWN is also opposed to the Trans Mountain Expansion Project and their views and scientific reports can be found at the Sacred Trust Initiative: The Coast Salish are a group of ethnically and linguistically related Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, living in the Canadian province of British Columbia and the U.S. states of Washington and Oregon. They speak one of the Coast Salish languages. The Nuxalk (Bella Coola) nation are usually included in the group, although their language is more closely related to Interior Salish languages.The Coast Salish are a large, loose grouping of many nations with numerous distinct cultures and languages. Territory claimed by Coast Salish peoples span from the northern limit of the Salish Sea on the inside of Vancouver Island and covers most of southern Vancouver Island, all of the Lower Mainland and most of Puget Sound and the Olympic Peninsula (except for territories of now-extinct Chemakum people). Their traditional territories coincide with modern major metropolitan areas, namely Victoria, Vancouver, and Seattle. The Tillamook or Nehalem around Tillamook, Oregon are the southernmost of the Coast Salish peoples.Coast Salish cultures differ considerably from those of their northern neighbours. They have a patrilineal and matrilineal kinship system, with inheritance and descent passed through the male and female line. According to a 2013 estimate, the population of Coast Salish numbers at least 56,590 people, made of 28,406 Status Indians registered to Coast Salish bands in British Columbia, and 28,284 enrolled members of federally recognized tribes of Coast Salish in Washington State.

PeoplesBelow is a list of some, but not all, Coast Salish-speaking tribes and nations located in British Columbia, Washington and Oregon. Chehalis people

Chimakum

Cowichan

The Cowichan designation is derived from the name of one of several groups forming the Cowichan Tribes band government, the Quwutsun. In the 19th century this term, or the variant \"Cowidgin\", was applied to all Halkomelem-speaking groups and certain others, such as the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and Semiahmoo. On Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, other \"Cowichan\" groups include the Penelakut, Lyackson and Lamalcha.

Cowlitz Tribe

Duwamish

Esquimalt

Halalt

Homalco

Klallam

K\'omoks (Comox)

Klahoose

Lamalcha (Hwlitsum)

Lummi (Lhaq\'temish)

Lyackson

Muckleshoot

Musqueam (xwməθkwəy̓əm)

Nisqually

Nooksack (Noxwsʼáʔaq)

Penelakut

Pentlatch

Puyallup

New Westminster Indian Band

Qualicum

Quileute

Saanich (W̱SÁNEĆ)

MÁLEXEŁ - Malahat First Nation

BOḰEĆEN – Pauquachin

SȾÁ, UTW̱ – Tsawout

W̱JOȽEȽP – Tsartlip

W̱SÍḴEM – Tseycum First Nation[1]

Samish

Sawhewamish (Sʼəhiwʼabš)

Scia\'new First Nation (Beecher Bay)

Semiahmoo (SEMYOME)

Shishalh (Sechelt)

Shoalwater Bay Tribe

Siletz

Skagits

Lower Skagit (Whidbey Island Skagits)

Upper Skagit

Skokomish (Twana)

Sliammon (Tla\'amin)

Snaw-naw-as (originally this term was used for both the Snuneymuxw/Nanaimo and the group that today uses this name, at Nanoose Bay)

Snohomish (Sduhubš)

Snokomish

Snoqualmie (Sduqwalbixw)

Snuneymuxw (Nanaimo)

Songhees (Lekwungen)

Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw)

Squaxin

Stillaguamish

Stó꞉lō

Aitchelitz

Chawathil

Cheam

Kwantlen

Kwikwetlem

Katzie

Leq\' a: mel

Matsqui

Popkum

Salish

Seabird Island

Skawahlook (Tait)

Shxw\'ow\'hamel

Skway (Shxwhá:y)

Skowkale

Skwah

Soowahlie

Sts\'Ailes (Chehalis, BC)

Sumas

Tzeachten

Yakweakwioose

Stz\'uminus First Nation (Chemainus + Ladysmith)

Suiʼaẋbixw

Suquamish (Suqwabš)

Swinomish

Tsawwassen

Tsleil-Waututh

T\'Sou-ke Nation

Tulalip (dxwlilap)

Twana

XacuabšHistory

This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.

Find sources: \"Coast Salish\" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (March 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message)

Main article: History of the Coast Salish peoplesThe history of Coast Salish peoples presented here provides an overview from a primarily United States perspective. Coast Salish peoples in British Columbia have had similar economic experience, although their political and treaty experience has been different—occasionally dramatically so.Evidence has been found from c. 3000 BCE of an established settlement at X̱á:ytem (Hatzic Rock) near Mission, British Columbia.[2] Early occupancy of c̓əsnaʔəm (Marpole Midden) is evident from c. 2000 BCE – 450 CE, and lasted at least until around the late 1800s, when smallpox and other diseases affected the inhabitants.[3][4] Other notable early settlements that record has been found of include prominent villages along the Duwamish River estuary dating back to the 6th century CE, which remained continuously inhabited until sometime in the later 18th century.[5] Boulder walls were constructed for defensive and other purposes along the Fraser Canyon[6] in the 15th century.Early European contact with Coast Salish peoples dates back to exploration of the Strait of Georgia in 1791 by Juan Carrasco and José María Narváez,[7] as well as brief contact with the Vancouver expedition by the Squamish people in 1792. In 1808, Simon Fraser of the North West Company entered Coast Salish territories via the Fraser Canyon and met various groups until reaching tidewater on the Fraser\'s North Arm, where he was attacked and repelled by Musqueam warriors. Throughout the 1810s, coastal fur trade extended further with infrequent shipping.The establishment of Fort Vancouver in 1824 was important as it established a regular site of interaction with Clackamas, Multnomah, and Cascades Chinooks, as well as interior Klickitat, Cowlitz, Kalapuya. Parties from the Hudson\'s Bay Company (HBC), led by John Work, travelled the length of the central and south Georgia Strait-Puget Sound.From the 1810s through to the 1850s, Coast Salish groups of Georgia Strait and Puget Sound experienced raiding from northern peoples, particularly the Euclataws and Haida.In 1827, HBC established Fort Langley east of present-day Vancouver, B.C. Whattlekainum, principal chief of the Kwantlen people, moved most of his people from Qiqayt (Brownsville) across the river from what was to become New Westminster to Kanaka Creek, near the Fort, for security and to dominate trade with the Fort. European contact and trade began accelerating significantly, primarily with the Fraser River Salish (Sto:lo).Fort Nisqually and its farm were established in 1833 by the Puget Sound Agricultural Company a subsidiary of the HBC, between present-day Olympia and Tacoma, Washington. Contact and trade began accelerating significantly with the southern Coast Salish. Significant social change and change in social structures accelerates with increasing contact. Initiative remained with Native traders until catastrophic population decline. Native traders and Native economy were not particularly interested or dependent upon European trade or tools. Trade goods were primarily luxuries such as trade blankets, ornamentation, guns and ammunition. The HBC monopoly did not condone alcohol, but freebooter traders were under no compunction.[8]Catholic missionaries arrive in Puget Sound around 1839–1840; interest diminished by 1843, and Methodist missionaries were in the area from 1840 to 1842 but had no success.The Stevens Treaties were negotiated in 1854–55, but many tribes had reservations and did not participate; others dropped out of treaty negotiations. (See, for example, Treaty of Point Elliott#Native Americans and # Non-signatory tribes.) From 1850 to 1854, the Douglas Treaties were signed on Vancouver Island between various Coast Salish peoples around Victoria and Nanaimo, and also with two Kwakwaka\'wakw groups on northern Vancouver Island. The Muckleshoot Reservation was established after the Puget Sound War of 1855–56.Through the 1850s and 1860s, traditional resources became less and less available. Sawmill work and employment selling natural resources began; Native men worked as loggers, in the mills, and as commercial fishers. Women sold basketry and shellfish. Through the 1870s, agricultural work in hop yards of the east Sound river valley increased, including cultivation of mushrooms.[9] The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic killed many, and commercial fisheries employment began to decline significantly through the 1880s.After legislation amending the Indian Act was passed the previous year, in 1885 the potlatch was banned in Canada; it was banned in the US some years later.[10] This suppression ended in the US in 1934, and in 1951 in Canada. Some potlatching became overt immediately.[11] A resurgence of tribal culture began in the 1960s; national Civil Rights movements engendered civil action for treaty rights.Chief Dan Georges delivered a pivotal speech in 1967 on what had happened to his people. This riveted audiences at a Canadian Centennial ceremony in Vancouver\'s Empire Stadium and touched off public awareness and native activism in BC and Canada. By this point, through the 1960s and 1970s, employment in commercial fisheries had greatly declined; employment in logging and lumber mills also declined significantly with automation, outsourcing, and the decline in available resources through the 1980s.The Boldt Decision, passed in 1974 upheld by the Supreme Court in 1979 was, based on the Treaty of Point Elliott of 1855 and restored fisheries rights to federally recognized Puget Sound tribes.Since the 1970s, many federally recognized tribes have developed some economic autonomy with (initially strongly contested) tax-free tobacco retail, development of casino gambling, fisheries and stewardship of fisheries. Extant tribes not federally recognized continue ongoing legal proceedings and cultural development toward recognition.[12] In British Columbia, 1970 marks the start of organized resistance to the \"white paper\" tabled by Jean Chrétien, then a cabinet minister in the government of Pierre Trudeau, which called for assimilation. In the wake of that, new terms such as Sto:lo, Shishalh and Snuneymuxw began to replace older-era names conferred by anthropologists, linguists and governments.

PopulationThe first smallpox epidemic to hit the region was in the 1680s, with the disease travelling overland from Mexico by intertribal transmission.[13] Among losses due to diseases, and a series of earlier epidemics that had wiped out many peoples entirely, e.g. the Snokomish in 1850, a smallpox epidemic broke out among the Northwest tribes in 1862, killing roughly half the affected native populations, in some cases up to 90% or more. The smallpox epidemic of 1862 started when an infected miner from San Francisco stopped in Victoria on his way to the Cariboo Gold Rush.[14] As the epidemic spread, police, supported by gunboats, forced thousands of First Nations people living in encampments around Victoria to leave and many returned to their home villages which spread the epidemic. Some consider the decision to force First Nations people to leave their encampments an intentional act of genocide.[15] Mean population decline 1774–1874 was about 66%.[16] Though the Salish peoples together are less numerous than the Cherokee or Navajo, the numbers shown below represent a small fraction of the group. Pre-epidemics about 12,600; Lushootseed about 11,800, Twana about 800.

1850: about 5,000.

1885: less than 2,000, probably not including all the off-reservation populations.

1984: sum total about 18,000; Lushootseed census 15,963; Twana 1,029.[9]

2013: an estimate of at least 56,590, made up of 28,406 Status Indians registered to Coast Salish bands in British Columbia, and 28,284 enrolled members of Coast Salish Tribes in Washington state.Culture

Social organizationExternalNeighboring peoples, whether villages or adjacent tribes, were related by marriage, feasting, ceremonies, and common or shared territory. Ties were especially strong within the same waterway or watershed. There existed no breaks throughout the south Coast Salish culture area and beyond. There were no formal political institutions.[17]External relations were extensive throughout most of the Puget Sound-Georgia Basin and east to the Sahaptin-speaking lands of Chelan, Kittitas and Yakama in what is now Eastern Washington. Similarly in Canada there were ties between the Squamish people and Sto:lo with Interior Salish neighbours, i.e. the Lil\'wat/St\'at\'imc, Nlaka\'pamux and Syilx.There was little political organization.[18] No formal political office existed. Warfare for the southern Coast Salish was primarily defensive, with occasional raiding into territory where there were no relatives. No institutions existed for mobilizing or maintaining a standing force.The common enemies of all the Coast Salish for most of the first half of the 19th century were the Lekwiltok aka Southern Kwakiutl, commonly known in historical writings as the Euclataws or Yucultas. Regular raids by northern tribes, particularly warriors of an alliance among the Haida, Tongass, and one group of Tsimshian, are also notable. Having gained superiority by earlier access to European guns through the fur trade, these warriors raided the southern Salish tribes for slaves and loot. Their victims organized retaliatory raids several times, attacking the Lekwiltok.[19]

InternalThe highest-ranking male assumed the role of ceremonial leader but rank could vary and was determined by different standards.[18] Villages were linked through intermarriage among members; the wife usually went to live at the husband\'s village, in a patrilocal pattern. Society was divided into upper class, lower class and slaves, all largely hereditary.[18] Nobility was based on genealogy, intertribal kinship, wise use of resources, and possession of esoteric knowledge about the workings of spirits and the world — making an effective marriage of class, secular, religious, and economic power. Many Coast Salish mothers altered the appearance of their free-born by carefully shaping the heads of their babies, binding them with cradle boards just long enough to produce a steep sloping forehead.[20]Unlike hunter-gatherer societies widespread in North America, but similar to other Pacific Northwest coastal cultures, Coast Salish society was complex, hierarchical and oriented toward property and status.Slavery was practiced, although its extent is a matter of debate.[21] The Coast Salish held slaves as simple property; they were not members of the tribe. The children of slaves were born into slavery.[22]The staple of their diet was typically salmon, supplemented with a rich variety of other seafoods and forage. This was particularly the case for the southern Coast Salish, where the climate of their territories was even more temperate.[23]The art of the Coast Salish has been interpreted and incorporated into contemporary art in British Columbia and the Puget Sound area.[citation needed]Bilateral kinship within the Skagit people is the most important system being defined as a carefully knit, and sacred bond within the society. When both adult siblings die, their children would be brought under the protection of surviving brothers and sisters, out of fear of mistreatment by stepparents.[24]The Salish Sea region of the Northwest coast has produced ancient pieces of art appearing by 4500 BP that feature various Salish styles recognizable in more recent historical works. A seated human feature bowl was used in a female puberty ritual in Secwépemc territory; it was believed to aid women in giving birth.[25]Salish-made bowls in the Northwest have different artistic designs and features. Numerous bowls have basic designs with animal features on the surface. Similar bowls will have more decorations including a head, body, wings, and limbs. A seated figure bowl is more complex in design, depicting humans being intertwined with animals.[26]For thousands of years, Northwest coast Salish people demonstrated valuing material possessions. They believe that material wealth included land, food resources, household items, and adornments. Material wealth not only improved one\'s life but it enhanced other qualities such as those needed to acquire high status. Wealth was required to enhance their status as elite born, or through practical skills, and ritual knowledge.[27] An individual could not buy status or power, but wealth could be used to enhance them. Wealth was not meant to be hidden. It has been publicly displayed through ceremony.

RecreationGames often involved gambling on a sleight-of-hand game known as slahal, as well as athletic contests. Games that are similar to modern day lacrosse, rugby and forms of martial arts also existed.[28]

BeliefsBelief in guardian spirits and shapeshifting or transformation between human and animal spirits were widely shared in many forms. The relations of soul or souls, and conceptions of the lands of the living and the dead were complex and mutable. Vision quest journeys involving other states of consciousness were varied and widely practised. The Duwamish had a soul recovery and journey ceremony.[19]The Quileute Salish people near Port Townsend had their own beliefs about where souls of all living things go. The shamans of these people believed everything had five components to its spirit; the body, an inner and outer soul, its life force, and its ghost.[29]: 106 They believed that an individual becomes ill when their soul is removed from their body and this is followed by death when the soul reaches the underworld. It is the job of the shaman to travel to the underworld to save the individual by recovering the soul while it is travelling between the two worlds.[29]: 106 The shamans[clarification needed] believed that once an individual\'s body was dead it was able to connect with its soul and shade in the underworld. It is believed that the spirits are able to come back amongst the living and cause family members to die of sickness and join them in the afterlife. Living individuals were terrified of the intentions of spirits. who only appear at night, prompting Salish people to travel only during the day and stay close to others for protection.[29]: 106 Coastal Salish beliefs describe the journey to the underworld as a two-day adventure. The individual must walk along a trail passing through bushes and a lake to reach a valley that is divided by a river where they will reside.[29]: 107 Salish beliefs about the afterlife very closely resemble the past life they lived, and they often assign themselves to jobs to keep busy, hunt for animals and game, and live with their families.Coastal Salish people believe that through dances, masks, or ceremonies they express themselve the spiritual powers that they are given. Spirit powers define a community\'s success through leadership, bravery, healing, or artistry. Spirit dancing ceremonies are common gatherings in the winter for members of the community to show their spirit powers through song, or dance.[30]: 31 The powers they acquired were sought after individually after going through trials of isolation where their powers related to spirit animals such as a raven, woodpecker, bear, or seal. Oftentimes members of the community get together to show their powers on the longhouse floor, where the spiritual powers are for the individual alone for each member to share and display various of the Coast Salish typically consisted of northwest coast longhouses made with western red cedar split planks and with an earthen floor. They provided habitation for forty or more people, usually a related extended family. Also used by many groups were pit-houses, known in the Chinook Jargon as kekuli (see quiggly holes). The villages were typically located near navigable water for easy transportation by dugout canoe. Houses that were part of the same village sometimes stretched for several miles along a river or watercourse.The interior walls of longhouses were typically lined with sleeping platforms. Storage shelves above the platforms held baskets, tools, clothing, and other items. Firewood was stored below the platforms. Mattresses and cushions were constructed from woven reed mats and animals skins. Food was hung to dry from the ceiling. The larger houses included partitions to separate families, as well as interior fires with roof slats that functioned as chimneys.[citation needed]The wealthy built extraordinarily large longhouses. The Suquamish Oleman House (Old Man House) at what became the Port Madison Reservation was 152 x 12–18 m (500 x 40–60 ft), c. 1850. The gambrel roof was unique to Puget Sound Coast Salish.[31]The Salish later took to constructing rock walls at strategic points near the Fraser River Canyon, along the Fraser River. These Salish Defensive Sites are rock wall features constructed by Coast Salish peoples.[32] One was excavated by Kisha Supernant in 2008 at Yale, British Columbia.[33] The functions of these features may have included defense, fishing platforms, and creation of house terraces. House pits and stone tools have been found in association with certain sites. Methods used include use of a total station for mapping the sites as well as the creation of simple test pits to probe for stratigraphy and artifacts.Native groups along the Northwest coast have been using plants for making wood and fiber artifacts for over 10,500 years. Anthropologists are searching for aquifer wet sites that would contain ancient Salish villages. These sites are created by a series of waters running through the archaeological deposits creating an environment with no oxygen that preserves wood and fiber[34] The wet sites would typically contain perishable artifacts that were used as wedges, fishhooks, basketry, cordage, and nets.

EthnobotanyThe Coast Salish use over 100 species of plants.[35] Salal is the source of multiple tinctures and teas, and its berries are often eaten during feasts.[36] They use the leaves of Carex to make baskets and twine.[37]

DietCoast Salish peoples\' had complex land management practices linked to ecosystem health and resilience. Forest gardens on Canada\'s northwest coast included crabapple, hazelnut, cranberry, wild plum, and wild cherry species.[38] There is also documentation of the cultivation of great camas, Indian carrot, and Columbia lily.[39]Anthropogenic grasslands were maintained. The south Coast Salish may have had more vegetables and land game than people farther north or among other peoples on the outer coast. Salmon and other fish were staples; see Coast Salish people and salmon. There was kakanee, a freshwater fish in the Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish watersheds. Shellfish were abundant. Butter clams, horse clams, and cockles were dried for trade.Hunting was specialized; professions were probably sea hunters, land hunters, fowlers. Water fowl were captured on moonless nights using strategic flares.The managed grasslands not only provided game habitat, but vegetable sprouts, roots, bulbs, berries, and nuts were foraged from them as well as found wild. The most important were probably bracken and camas; wapato especially for the Duwamish. Many, many varieties of berries were foraged; some were harvested with comblike devices not reportedly used elsewhere. Acorns were relished but were not widely available. Regional tribes went in autumn to the Nisqually Flats (Nisqually plains) to harvest them.[23]Salish groups such as Muckleshoot were heavily reliant on seasonal foods that included animals and plants. In January, they would gather along the river banks to catch salmon. By May, Salmonberry sprouts would be eaten with salmon eggs. Men would hunt deer and elk, while women gathered camas and clams from the prairies and beaches. By the summer, steelhead and king salmon appeared in masses along the rivers, and berries were abundant in the forests.[40] This harvesting cycle is referred to as the Seasonal Rounds.[41]

In literature and TVLegends of Vancouver by Canadian author E. Pauline Johnson (Tekahionwake) is a collection of Coast Salish \"as told-to\" narratives, stemming from the author\'s relationship to Squamish Chief Joe Capilano. It first appeared in 1911, now available online from UPenn Digital Library.[42]Victoria, British Columbia author Stanley Evans has written a series of mysteries featuring a Coast Salish character, Silas Seaweed, from the fictitious \"Mohawt Bay Band\", who works as an investigator with the Victoria Police Department.[43]In the third episode of the first season of the 2017\'s Taboo, Tom Hardy\'s character James Delaney visits the grave of his mother, whose name is \"Salish\".[44]In 2022, filmmaker Ryan Abrahamson of the Spokane Tribe created a supernatural thriller featuring the Coast Salish language.[45]

See also Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast

Interior SalishTerminologyThe use of the term Coast Salish, and its association with an attribute of nationhood, has increasingly become resisted, as that notion of a \'national\' grouping is not a traditional part of the culture of Salish communities in this area, and as the term derives more from anthropology than community self-description. The phenomenon replacing this terminology is increasingly to indicate the specific tribe in question, or otherwise to use terms not given by non-Indigenous entities.[46]

CHIEF DAN GEORGE NEGATIVES SCARCE Tsleil-Waututh Nation FAMOUS PHOTOGRAPHER $300.00

CERAMIC TILE "CHIEF DAN GEORGE" ART BY HARMONY DESIGN 8”x 8” $19.99

1972 Press Photo Chief Dan George signs autograph for Ginger Otipoby in Dallas. $19.99

1969 Press Photo Chief Dan George & Mark Slade in "High Chaparral" - hcp89520 $19.99

Press Photo Chief Dan George - syp10306 $15.99

Press Photo Patrick Wayne & Chief Dan George in "The Bears and I" Movie $19.99

Chief Dan George at 19th Annual Grammy Awards at the Hollywood Pal- Old Photo 1 $5.90

Dan Clougherty Official Happy Hour Master Drink Index Bartender Recipes 100+ $18.00

|