|

On eBay Now...

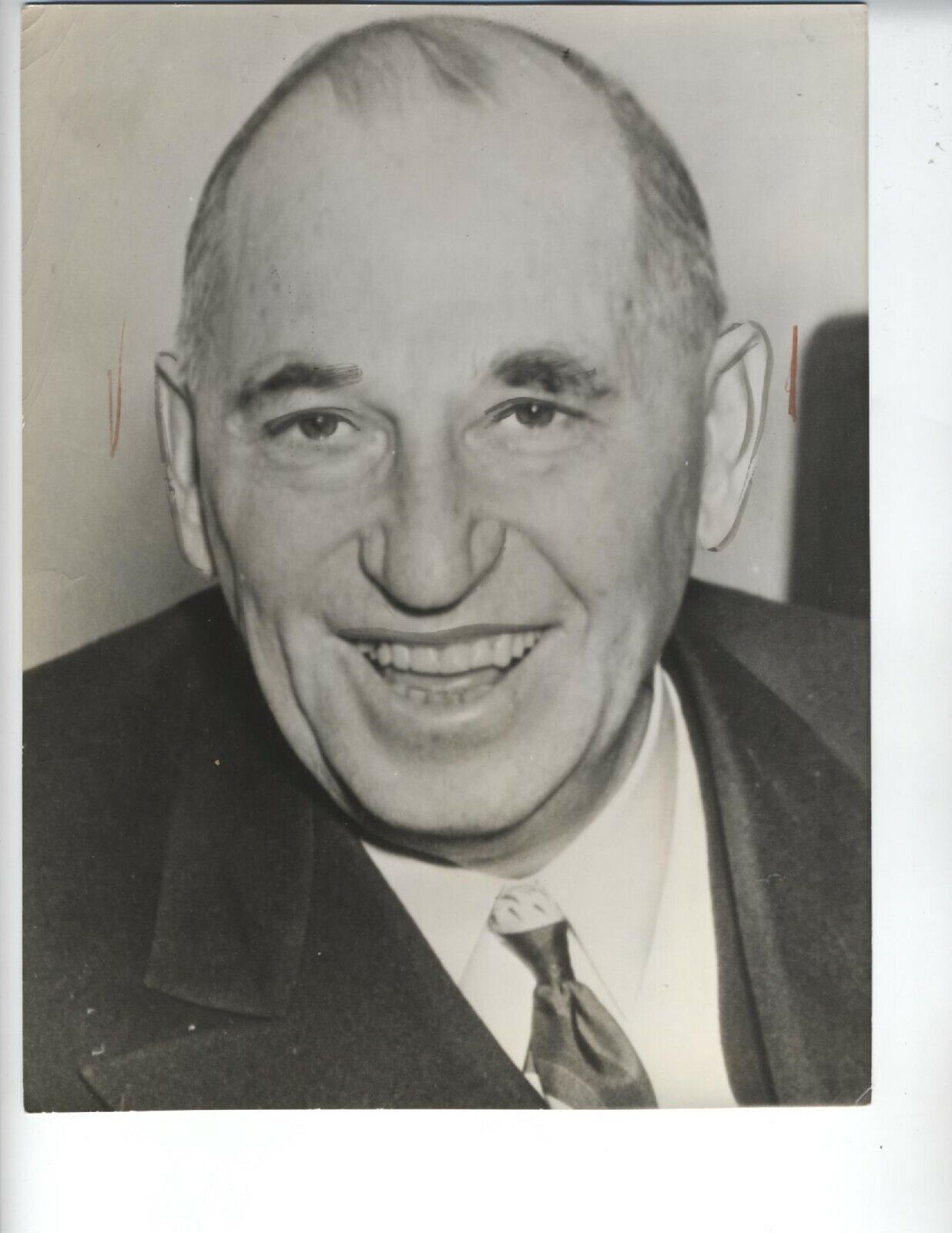

1940 VINTAGE ORIGINAL PHOTO WALTER CHRYSLER AUTOMOBILE LEGEND LONG ISLAND For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1940 VINTAGE ORIGINAL PHOTO WALTER CHRYSLER AUTOMOBILE LEGEND LONG ISLAND:

$268.04

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL PHOTO OF WALTER P. CHRYSLER MEASURING 8X10 INCHERS FROM 1940 DIED ON HIS LONG ISLAND ESTATE

Walter Percy Chrysler (April 2, 1875 – August 18, 1940) was an American automotive industry executive and founder of Chrysler Corporation, now a part of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles.Contents1 Early life2 Ancestry3 Railroad career4 Automotive career5 Later years6 See also7 References8 Bibliography9 External linksEarly lifeChrysler was born in Wamego, Kansas, the son of Anna Maria (née Breymann) and Henry Chrysler.[1] He grew up in Ellis, Kansas, where today his boyhood home is a museum. His father was born in Chatham, Ontario in 1850 and immigrated to the United States after 1858.[2] A Freemason,[3] Chrysler began his career as a machinist and railroad mechanic in Ellis. He took correspondence courses from International Correspondence Schools in Scranton, Pennsylvania, earning a mechanical degree from the correspondence program.

AncestryWalter Chrysler\'s father, Henry (Hank) Chrysler, was a Canadian-American of German and Dutch ancestry. He was an American Civil War veteran who was a locomotive engineer for the Kansas Pacific Railway and its successor, the Union Pacific Railroad.[4] Walter\'s mother was born in Rocheport, Missouri, and was also of German ancestry.[5] Walter Chrysler was not especially interested in his remote ancestors; his collaborative author Boyden Sparkes says that one genealogical researcher reported \"that he had a sea-going Dutchman among his forebears; one Captain Jan Gerritsen Van Dalsen\", but that \"as to that, Walter Chrysler made it plain to me he was in accord with Jimmy Durante: \'Ancestors? I got millions of \'em!\'.\"[6] However, he thought enough of genealogy to include in his autobiography that his father, Hank Chrysler, \"Canadian born, had been brought from Chatham, Ontario, to Kansas City when he was only five or six. His forebears had founded Chatham; the family stock was German; eight generations back of me there had come to America one who spelled his name Greisler, a German Palatine. He was one of a group of Protestants who had left their German homeland in the Rhine Valley, gone to the Netherlands, thence to England and embarked, finally, from Plymouth for New York.\"

Other researchers have since traced his ancestors in more detail. Karin Holl\'s monograph on the subject[7] traces the family tree to a Johann Philipp Kreißler, born in 1672, who left Germany for America in 1709. Chrysler\'s ancestors came from the Rhineland-Palatinate town of Guntersblum. His family belongs to Old Stock Americans.

Railroad careerChrysler apprenticed in the railroad shops at Ellis as a machinist and railroad mechanic. He then spent a period of years roaming the west, working for various railroads as a roundhouse mechanic with a reputation of being good at valve-setting jobs. Chrysler moved frequently, first to Wellington, KS in 1897, then to Denver, CO and finally Cheyenne, WY.[8] Some of his moves were due to restlessness and a too-quick temper, but his roaming was also a way to become more well-rounded in his railroad knowledge. He worked his way up through positions such as foreman, superintendent, division master mechanic, and general master mechanic.

From 1905–1906, Chrysler worked for the Fort Worth and Denver Railway in Childress in West Texas. He later lived and worked in Oelwein, Iowa, at the main shops of the Chicago Great Western where there is a small park dedicated to him.[9][10]

The pinnacle of his railroading career came at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he became works manager of the Allegheny locomotive erecting shops of the American Locomotive Company (Alco). While working in Pittsburgh, Chrysler lived in the town of Bellevue, the first town outside of Pittsburgh on the north side of the Ohio River.

Automotive careerChrysler\'s automotive career began in 1911 when he received a summons to meet with James J. Storrow, a banker who was a director of Alco. Storrow asked him if he had given any thought to automobile manufacture. Chrysler had been an auto enthusiast for over five years by then, and was very interested. Storrow arranged a meeting with Charles W. Nash, then president of the Buick Motor Company, who was looking for a smart production chief. Chrysler, who had resigned from many railroading jobs over the years, made his final resignation from railroading to become works manager (in charge of production) at Buick in Flint, Michigan.[11] He found many ways to reduce the costs of production, such as putting an end to finishing automobile undercarriages with the same luxurious quality of finish that the body warranted.

In 1916, William C. Durant, who founded General Motors in 1908, had retaken GM from bankers who had taken over the company. Chrysler, who was closely tied to the bankers, submitted his resignation to Durant, then based in New York City.This plaque is located in the lobby of the Chrysler BuildingDurant took the first train to Flint to make an attempt to keep Chrysler at the helm of Buick. Durant made the then-unheard of salary offer of US$10,000 (US$230,000 in today\'s dollars) a month for three years, with a US$500,000 bonus at the end of each year, or US$500,000 in stock. Additionally, Chrysler would report directly to Durant, and would have full run of Buick without interference from anyone. Apparently in shock, Chrysler asked Durant to repeat the offer, which he did. Chrysler immediately accepted.

Chrysler ran Buick successfully for three more years. Not long after his three-year contract was up, he resigned from his job as president of Buick in 1919. He did not agree with Durant\'s vision for the future of General Motors. Durant paid Chrysler US$10 million for his GM stock. Chrysler had started at Buick in 1911 for US$6,000 a year, and left one of the richest men in America. GM replaced Chrysler with Harry H. Bassett a protege who had risen through the ranks at the Weston-Mott axle manufacturing company, by then a subsidiary of Buick.

Chrysler was then hired to attempt a turnaround by bankers who foresaw the loss of their investment in Willys-Overland Motor Company in Toledo, Ohio. He demanded, and received, a salary of US$1 million a year for two years, an astonishing amount at that time. When Chrysler left Willys in 1921 after an unsuccessful attempt to wrestle control from John Willys, he acquired a controlling interest in the ailing Maxwell Motor Company. Chrysler phased out Maxwell and absorbed it into his new firm, the Chrysler Corporation, in Detroit, Michigan, in 1925. In addition to his namesake car company, Plymouth and DeSoto marques were created, and in 1928 Chrysler purchased Dodge Brothers and renamed it Dodge. The same year he financed the construction of the Chrysler Building in New York City, which was completed in 1930. Chrysler was named Time magazine\'s Man of the Year for 1928.[12]

He was inducted into the Automotive Hall of Fame in 1967.[13]

Later years

The mausoleum of Walter Chrysler in Sleepy Hollow CemeteryIn 1923, Chrysler purchased a twelve-acre waterfront estate at Kings Point on Long Island, New York [14] from Henri Willis Bendel and renamed it \"Forker House.\" In December 1941, the property was sold to the U.S. government\'s War Shipping Department and became known as Wiley Hall as part of the United States Merchant Marine Academy.[15] He also built a country estate in Warrenton, Virginia, in what is referred to as the Virginia horse country and home to the Warrenton Hunt. In 1934, he purchased and undertook a major restoration of the famous Fauquier White Sulphur Springs Company resort and spa in Warrenton. Sold in 1953, the property was developed as a country club, which it remains today.

On the estate he inherited, Walter P. Chrysler Jr. established North Wales Stud for the purpose of breeding Thoroughbred horses. Chrysler, Jr. was part of a syndicate that included friend Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt Jr. who in 1940 acquired the 1935 English Triple Crown winner Bahram from the Aga Khan III. Bahram stood at stud at Vanderbilt\'s Sagamore Farm in Maryland then was brought to Chrysler\'s North Wales Stud.

Chrysler turned 61 in the spring of 1936 and decided to step down from an active role in the day-to-day business of the company. Two years later, Della died at the age of 58 and Walter, devastated at the loss of his childhood sweetheart, suffered a stroke. His previously robust health never recovered from this, and he succumbed to a cerebral hemorrhage in August 1940 at Forker House which is in Kingspoint New York. He was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York. [16]

“The real secret of success is enthusiasm”

Walter Chrysler built his company through superior management and engineering. Chrysler was born in Wamego, Kansas in 1875. His father was a locomotive engineer, which undoubtedly influenced Chrysler’s decision to enroll in a four-year machinist apprenticeship at age 18. Chrysler began his career in the railroad industry, working for the Santa Fe Railroad and later becoming a master mechanic and superintendent for the Chicago Great Western railroad.

It wasn’t until the 1908 Chicago Auto Show that Chrysler began to take an interest in automobiles. He purchased a Locomobile touring car, but instead of driving it, he immediately disassembled the car to see how it worked. In 1911 Chrysler met with Charles Nash, then president of GM, who offered Chrysler a job as production chief for Buick in Flint, Michigan. Chrysler found numerous ways of cutting production costs and was eventually made president of Buick. He retired in 1919 in opposition of Durant’s vision for General motors. However, his retirement did not last long. Later that year, Chrysler was approached by a group of bankers who controlled the debt of Willys-Overland Motor Company. They wanted Chrysler to curb the financial bleeding and paid him an astonishing salary of $1 million per year to do so. Chrysler drastically reduced Willys-Overland’s debt and even attempted a takeover of the company from John North Willy’s in 1921, but was unsuccessful. Later that year, Chrysler acquired a controlling interest in the floundering Maxwell Motor Company. He built the first car bearing his own name in 1924, which was a very sophisticated automobile equipped with four-wheel hydraulic brakes, a replaceable oil filter, and capable of achieving 70 mph.

Chrysler reorganized Maxwell into the Chrysler Corporation in 1925. He acquired Dodge Brothers Inc. in 1928, as well as Plymouth and De Soto. He was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” in 1929 and his name was also emblazoned on New York’s tallest skyscraper. Chrysler stepped down as president of his company in 1935 and remained chairman until his death in 1940. By analyzing problems and resolving them through decisive action, Walter Chrysler succeeded where many automotive pioneers failed, and laid the groundwork for his company to become one of Detroit’s legendary “Big Three.”Chapter One – Walter P. ChryslerThe fun I had experienced in making things as aboy was magnified a hundredfold when I beganmaking things as a man. There is in manufacturing acreative joy that only poets are supposed to know. Someday I’d like to show a poet how it feels to designand build a railroad locomotive.— Walter P. Chrysler, Life of anAmerican Workman (1937)For the American automobile industry, 1908 was a watershed year. Henry Fordintroduced his Model T; William C. (Billy) Durant formed the General Motors Company;and the Locomobile became the first American auto to win the Vanderbilt Cup Raceagainst European competitors.It was also the year Walter P. Chrysler bought his first car.Anyone who knew Walter Chrysler from his early years would not have beensurprised by his decision to purchase the vehicle, a shining new Locomobile. Born April2, 1875, on his parents’ fourth wedding anniversary, in Wamego, Kansas, some 35miles west of Topeka, Walter grew up in a railroad family. Throughout his life, he wasalways fascinated with the workings of machinery.Walter was the third child of Henry Chrysler (1850–1916), always known asHank, and Anna Marie Breymann Chrysler (1852–1926), more commonly called Mary.Hank Chrysler worked as a locomotive engineer for the Union Pacific Railroad hisentire adult life, and the family lived in several Union Pacific railroad towns. In 1879, theChryslers moved from Wamego to Ellis, Kansas, after Hank Chrysler was given theJunction City (Kansas) to Ellis run. Located about 170 miles west of Wamego, Ellis hadlarge Union Pacific repair shops. These shops were Walter Chrysler’s true boyhoodhome.Working on the RailroadAn inquisitive child, the young Chrysler was also willful and early ondeveloped a burning ambition.Like many working families, the Chryslers supplemented their household income

2with domestic enterprise. As a boy, Walter sold calling cards and silverware door-to-doorin Ellis. His mother also ran a milk business, and Walter was pressed into servicedelivering milk and cream to about 20 homes. He worked as a delivery boy for a localgrocery store one summer and then returned there briefly after finishing high school in1892.Walter’s dream, however, was to work for the railroad like his father. Olderbrother Ed had already entered the Union Pacific Railroad’s apprentice machinistprogram in Ellis, and Walter yearned to follow in his footsteps. But Hank would havenone of it. Wanting at least one son to go to college, Walter’s father refused to sign thenecessary papers giving his younger son permission to join the program.Undeterred, Walter defied his father, applied for a job as a sweeper in themachine shop and went to work cleaning floors rather than attending class. So diligentlydid he apply himself to the less-than-glamorous job, he soon attracted the attention of theshop’s master mechanic, Edgar Esterbrook. It would be Esterbrook who, impressed withWalter’s work habits, convinced Hank Chrysler to relent in the test of wills betweenfather and son and allow Walter to enroll in the machine shop’s four-yearapprenticeship.As an apprentice, Walter’s knack for the mechanical quickly became manifest.He made his own tools, beginning with a set of calipers and a depth gauge. At age 18,he built an operating 28-inch model of the locomotive his father ran, complete with a tinysteam whistle. He operated the locomotive on a set of tracks he laid behind the familyhome in Ellis.During his apprenticeship, he tried to understand every operation and machinehe saw. In the shops, he worked closely with more experienced machinists, a numberof whom remarked on his intelligence and diligence and agreed to serve as his mentors.The most important of these was Walter Darling, an experienced and grizzled mechanicat the Union Pacific’s Ellis shops.Darling taught Chrysler how properly to set a locomotive’s slide valves, whichcontrolled the steam intake and exhaust. This was a prized skill, because the slide valvesettings determined how much power the locomotive would develop. Althoughlocomotive manufacturers set “port marks” on the valve gear showing the location of thepiston at the very end of the stroke, these marks were often inaccurate due to wear andtear on the valve gear.

3From Darling, Chrysler learned to create his own port marks before settingvalves — and to trust only those he made himself. Following Darling’s advice, theyoung machinist soon developed a reputation for setting valves quickly and accurately.For the rest of his life, Walter Chrysler could tell by the sound of an operatinglocomotive if its slide valves were properly set.In these years, Chrysler’s intellectual drive became increasingly evident. At theturn of the century, Scientific American was a source of scientific and mechanicalinformation for young amateurs and eccentric tinkers alike, and Chrysler was an avidreader of the magazine. He mailed scores of questions to the periodical’s question-andanswer column and enrolled in dozens of correspondence courses covering topicsranging from drafting to mechanical and electrical engineering.Outside his enthusiasms, however, Chrysler was hardly studious and certainlyno bookworm. Known in his teens as something of a hellion, he often displayed wellinto his 20s a very hot temper (or, as he called it years later, “a short fuse”). Thisfeistiness, combined with his intelligence and his growing ambition, produced a youngman so confident in his own abilities that he was sometimes cocky, if not arrogant.By the end of his apprenticeship, Chrysler was looking for opportunities beyondthose offered in Ellis. In later years, he would become known as a corporate risk-taker.But when he left his hometown in 1897 at age 22, he was already willing to move intonew endeavors in new places, sometimes at less pay, in order to advance his career.Chrysler seemed to enjoy the itinerant mechanic’s vagabond life, with the ruggedfellowship of its volatile and open society, as he moved through more than two dozenjobs involving locomotive repair work over the next decade.A big man, hale and bluff and sometimes profane, he fared well with the folks heencountered on the road. One measure of the impact he had on them was the way hequickly advanced to positions involving more and more responsibility. His first job afterleaving Ellis was as a journeyman machinist for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa FeRailroad at its shops in Wellington, Kansas. Walter bounced between a dozen shortlived jobs, including a brief stint back at the Union Pacific shops in Ellis, before taking aposition as roundhouse machinist for the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad in SaltLake City during 1900.Although he enjoyed the freedom and challenges of wandering from job to jobon the western railroads, the young man, however driven, was often lonely. Walter

4missed his family in Ellis and more important, he missed Della V. Forker, his childhoodfriend and sweetheart. He later wrote:I knew the answer to my lonesomeness: Della Forker. We exchanged lettersfaithfully. She never wavered during that time when I was a wanderingmechanic; she knew why I was roving, knew that she was completelyinterwoven with my ambitions.Walter and Della had been engaged in 1896, but he was in no position to marry her at atime when he was earning only $1.50 a day and striving to make his way in a wider world.Having garnered an apparently steady job in Salt Lake City, Chrysler now feltcomfortable returning to Ellis to marry Della. The two were wed in the town’s Methodistchurch on June 7, 1901.In a sense, Chrysler had settled down, and the birth of the couple’s first child,Thelma Irene, on February 13, 1902, instantly turned him into a dedicated family manwho took his responsibilities seriously. But, as the son of a railroad man, Chryslercertainly knew there would be frequent and future moves, and marriage had notchanged the essentials of his character. Neither had it changed his burning need todominate his working world nor his willingness to gamble on change for the chance ofadvancement. Throughout Walter’s roller-coaster career, Della would support hisdreams, go along with his gambles and always believe in him. He, in turn, would oftencredit her with his success and, ultimately, would dedicate his autobiography, Life of anAmerican Workman, to her.In short, a married Walter Chrysler was only that much more determined to getahead. His reputation as a “can-do” mechanic and his quick promotions to better andbetter jobs marked his work for the Denver & Rio Grande Western in Salt Lake City.There, in the fall of 1901, he displayed just what the combination of careful mastery ofskills, drive and innate ability could accomplish. A locomotive that returned to theroundhouse with a blown back cylinder was needed for an important run to Denver inthree hours. Normally, this repair job would take at least five hours to complete. JohnHickey, the master mechanic, asked Chrysler to do the impossible. He confidentlyagreed to take on the job, and the locomotive was repaired and ready to run on time. Asa reward for this and other such work, the railroad made Walter Chrysler roundhouseforeman in February 1902, putting him in charge of 90 men at the Salt Lake City

5roundhouse, with a salary of $90 a month.Chrysler left the Denver & Rio Grande Western Railroad in the spring of 1903 tobecome the general foreman for the Colorado & Southern Railroad shops in Trinidad,Colorado, at age 28. In less than two years, he was the division master mechanic for thecompany, earning $160 a month.Walter Chrysler’s wandering days, however, were by no means over. He spent1905 working as the general foreman of the mechanical department for the Fort Worth &Denver City Railroad in barren Childress, Texas. In December 1905, while Chrysler wasstill in Childress, John Chisholm of the Chicago Great Western Railroad offered him thejob of master mechanic at the railroad’s stateof-the-art locomotive repair shops inOelwein, Iowa, at a salary of $200 a month. Chicago Great Western would prove to bethe last railroad at which Walter Chrysler worked.Chrysler took the job in early January 1906, and on April 4, 1906, Della gavebirth to their second child, Bernice. By May 1907, less than two years after moving thefamily to Oelwein, Walter became general master mechanic for the entire railroad. InDecember 1907, the Chicago Great Western Railroad named the 32-year-old Chryslersuperintendent of motive power for its entire system, making him the youngest man toever hold this post. With the job came the responsibility of managing all the railroad’slocomotives and supervising about 1,000 men, including locomotive engineers andfiremen and all the men working at the roundhouse and repair shops. His responsibilitiescovered locomotives and other equipment worth millions of dollars. The railroad paidhim the respectable salary of $350 a month.The following year, Chrysler bought the Locomobile.Of the TrackWalter Chrysler set eyes on the fascinating machine for the first time at the 1908Chicago Automobile Show. He had traveled to the Windy City on a business trip, and, ashe later described the moment:That is where it happened. I saw this Locomobile touring car; it was paintedivory white and the cushions and trim were red. The top was khaki,supported on wood bows. Straps ran from that top to anchorages on eitherside of the hood. On the running board there was a handsome tool box thatmy fingers itched to open. Beside it was a tank of gas to feed the head

6lamps; just behind the hood on either side of the cowling was an oil lamp,shaped quite like those on horse drawn carriages. I spent four days hangingaround the show, held by that automobile as by a siren’s song.No question Chrysler longed to buy the car, and not simply to ride it aroundOelwein. “I wanted the machine,” he said, “so I could learn all about it.” But theLocomobile carried a price tag of $5,000, and Chrysler’s repeated inquiries revealedthere was no room to bargain. He had only $700 in savings (and that monthly salary of$350), so he turned to a friend, Ralph Van Vechten, who came from a prominent family ofIowa bankers and was now vice president of the Continental National Bank of Chicago.Before the week was out, Chrysler had badgered Van Vechten into helping him buy theLocomobile. Van Vechten agreed to lend Chrysler the $4,300 he needed, but only afterWilliam Causley, a Chicago Great Western Railroad official, promised to cosign the loan.Chrysler had no idea how to operate the vehicle when he bought it. Even if hehad, given the primitive condition of the roads, he would not have been able to drive itback to Oelwein. He had the automobile shipped home by rail and then pulled out to hishouse by a team of horses. Della was waiting, wild with enthusiasm, but Walter refusedto take her for a ride. Instead, he moved the Locomobile into the barn behind the familyhome and spent the next three months taking it apart, studying its mechanical systemsand reassembling it. He scoured automobile catalogues and technical literature to helphim better understand his expensive new toy. He worked every evening and everyweekend studying the sleek machine. When he finally took the car out for a spin, he droveit off the road and into a neighbor’s garden and had to have a team of horses pull it out ofthe mud. Walter and Della Chrysler then headed for town, where he nearly ran over acow on the main street. By the end of that day, sweaty and exhausted, Walter Chryslerhad learned to drive a car.A scant three years later, Walter would himself enter the auto business. Theywould be three tumultuous years, partly because of Walter’s own restlessness. On May27, 1909, Della gave birth to the Chryslers’ third child. Walter, his wife, his daughters,Thelma and Bernice, and his new son, Walter P., Jr., could look forward to livingcomfortably in Oelwein. Walter had a good job, an important one that put him in chargeof anything that moved along the railroad and anyone who moved it and making sure itmoved on time. By the standards of Oelwein, the family was successful: if not rich, they

7were at least secure. Unlike most of the other young couples they knew, the Chryslerseven owned a car. But though Walter was the mechanical head for the entire ChicagoGreat Western system, he knew that one of the unwritten but inflexible laws of railroadingwas that a mechanic never reaches the top, never gets to sit in the executive’s chair. Hemight indeed be “learning plenty,” as Walter claimed to be, but he was also, he admitted,“still seething with ambition.” So, when trouble came at the Chicago Great Western, itwas not just that his temper got the better of him, which it did, but even more that he wasalready thinking about his next career move.In 1908, the railroad had come under the control of new management, whomoved the headquarters from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Chicago and named SamuelMorse Felton as president. Walter described him as a man of “gouty disposition,” whocertainly was hard to please. Determined to get along, Chrysler had been working 19hours a day and spending four nights a week on the road.At home in Oelwein one night in mid-December 1909, he got a midnightsummons to appear in Chicago the following morning. When he dragged himself the nextday into Felton’s office, his boss seemed momentarily to forget why he had calledChrysler in. Then, digging through a pile of papers on his desk, Felton came up with areport that a “hot box,” or overheated wheel bearing, had made one train three minuTesla Referralte. He demanded an explanation of the trivial problem, and Chrysler, enraged andinsulted, responded with some quite colorful language. Felton began to rant and rave.When Chrysler reached into his pocket, Felton fell quiet. Chrysler pulled his batch ofrailroad passes, the symbol of his job and authority, from his wallet, tossed them onFelton’s desk and stomped out. “That,” he wrote, “is how I became an ex-railroad man.”Chrysler immediately telegraphed Waldo H. Marshall, an old friend and presidentof the American Locomotive Company (ALCO), asking for a job. He accepted theposition of general foreman of ALCO’s Allegheny shops in Pittsburgh, where thecompany manufactured locomotives. The salary of $275 a month was less than hisrailroad pay of $350 a month, but Chrysler, in typical fashion, saw this as only atemporary setback, since the job opened up more important long-range prospects. In ayear and a half, he was works manager of the Allegheny shops and had turned theoperation around, making it profitable for the first time in three years. By spring 1911,Chrysler was earning $8,000 a year, more than $650 a month, when James J. Storrow,a director of ALCO and of the General Motors Company, offered him the opportunity to

8work in the automobile industry.Storrow was the president of Lee, Higginson and Company, one of the largestinvestment banks of the time. From his position on the board of ALCO, he knew of thegenius Chrysler had shown in profitably manufacturing locomotives and wanted to bringhis talents to General Motors. Specifically, Storrow wanted to make Chrysler worksmanager for the huge Buick plant in Flint, Michigan. Chrysler discussed the possibilitieswith the investment banker at his New York office and agreed to meet later with CharlesW. Nash, the tight-fisted president of the Buick Motor Company. Chrysler and Nash hadlunch in Pittsburgh, and they agreed that Chrysler would come to Flint to visit the Buickplant. In the meantime, James McNaughton, a vice president at ALCO, offered Chryslera salary of $12,000 a year to keep him in Pittsburgh.Walter Chrysler visited Flint in the fall of 1911 and spent a couple of dayschecking out the Buick plant. What he saw was a remarkably backward, inefficientmanufacturing operation where craftsmen were hand-building automobiles much thesame way they had built fine horse-drawn carriages decades earlier.In his bones, Walter felt a challenge calling. He had, he knew, the opportunity tomake an immediate impact at Buick. He told Nash he would take the job. Nash learnedthat Chrysler had been offered $12,000 to stay at ALCO but could bring himself to offerhim only $6,000 to come to Buick — which was not only half what Chrysler had beenpromised if he stayed but also $2,000 less than of times before in his career, promptlyaccepted the cut in pay, banking on his talent and drive to bring him success, even fame,in this freewheeling new automobile industry. Nash formally offered Chrysler the positionon November 10, 1911, but Walter did not move to Flint until late January 1912. He hadan important project to attend to and an important event to celebrate first — a largeorder at ALCO for 25 locomotives for the Pittsburgh & Lake Erie Railroad, plus the birthof his fourth child, Jack Forker Chrysler, on January 7, 1912.The Buick YearsWalter Chrysler’s tenure as Buick works manager from January 1912 throughJune 1916 was a smashing success by any measure. He applied many of the operatingpractices he had perfected at ALCO to the manufacture and assembly of automobiles.The most important of these was basic cost accounting. When he first came toBuick, he asked the plant clerk for a schedule of piecework rates paid to the various

9categories of workers and found that no schedule existed that would permit him todetermine production costs. He noted:In the Allegheny works of American Locomotive, we had to offer $40,000 orso on a locomotive job; offerding low enough to get the job and still make aprofit. The only way we could do that was to know to a penny what it wascosting us to drill a hole and what it cost us to make an obscure little casting.At Buick, Chrysler found skilled craftsmen assembling one car at a time on fixedbenches, applying multiple coats of paint on areas of the car that nobody would ever see.He reduced chassis assembly time from four days to two by getting rid of theunnecessary painting. He later cut the paint drying time in half by raising the temperaturein the drying ovens.In the main assembly building, a forest of thousands of vertical posts placed closetogether hindered production. Chrysler installed a roof truss of superior design, allowingfor the removal of most of the posts. By simplifying the assembly process, Chryslerremoved much of the excess clutter of parts and components from the factory floor andgreatly increased the productivity of men and machines alike.Experimenting along the same lines as Henry Ford at his factory in HighlandPark, Michigan, he also introduced a crude assembly line at Buick, where workerspushed the unfinished chassis along tracks through the assembly area. Using the samefactory floor space and workforce, Chrysler immediately expanded Buick production from45 cars a day to 75 and eventually to more than 200. In 1912, Buick had built 19,812vehicles at its Flint plant, but in 1916 — under Chrysler’s leadership — production jumpedmore than six-fold, to 124,834 cars. The quality of the product also improved thanks tothe system of instant rolling changes and improvements introduced by Chrysler, a systemthat would become characteristic of his own company in the 1920s and 19030s.Chrysler’s salary at Buick, however, failed to reflect his accomplishments. Threeyears after leaving ALCO for Buick, Chrysler was still earning his original salary of$6,000 a year. He went to see Charlie Nash, demanded an increase to $25,000 a yearand threatened to quit if he did not get it. A reluctant Nash, who had become presidentof General Motors, consulted with James Storrow and, pushed by the banker, grantedChrysler his raise. Brazen and confident as ever, Chrysler then warned Nash that hewould ask for $50,000 the following year. Nash gave him that raise as well, for he was

10sold on Walter Chrysler. The man was worth every penny, considering the millions ofdollars in profits he generated for Buick.Meanwhile, change was in the wind at GM. The company had been founded in1908 by Billy Durant, one of the more colorful executives in automobile history. Asalesman and a schemer, Durant loved to dream big. His attempt to purchase everyautomobile company and every parts supplier he could lay his hands on had gottenGeneral Motors into financial straits, and, as a result, the volatile Durant lost control of hiscompany in 1911 to a collection of bankers led by James Storrow. In September 1915,Durant managed to regain control of GM, but he waited until June 1916 to take theposition of president back from Charlie Nash.The maneuvers that took place between the two executives created a dilemmafor Walter Chrysler. First, Storrow, ousted by Durant, tried to buy Packard Motor CarCompany early in 1916, hoping he could get Nash and Chrysler to run it. But Storrow’soffer for Packard failed, and instead he bought the Jeffery Company of Kenosha,Wisconsin, in June 1916. Storrow set up Nash as its president, and both men wantedChrysler to join them. But Billy Durant made Chrysler an offer he could not refuse — hewould become president of Buick and be paid a salary of $500,000 a year for threeyears. Chrysler stayed.Billy Durant’s and Walter Chrysler’s very different personalities guaranteedconflict between the two. Although he was not averse to taking risks when they madesense, Chrysler was also a careful planner and stickler for detail, a man who took thetime to understand the business — and its products — thoroughly. He wanted to followwell-thought-out and consistent plans and policies. Durant was more a shoot-from-thehip man, one who operated on inspiration, even whimsy, and who often changed hismind (and his policies) several times a day. Durant agreed to give Chrysler completeautonomy at Buick, with no interference from above, but he simply could not stick to hispromise. He consistently second-guessed Chrysler and interfered with his running of thecompany.Not that Durant failed to recognize Chrysler’s talent; Billy knew what he had inWalter, and the freewheeling president pushed his clever, clear-eyed junior executive upthe corporate ladder. Late in 1918, Durant named Chrysler first vice president of GeneralMotors, with broad responsibility for all GM operations. Among other things, in April 1919Walter Chrysler launched the Modern Housing Corporation, a GM subsidiary that would

11build 1,000 homes for housing-starved GM workers in Flint. It was the kind of program thatDurant, lacking Chrysler’s connection to the ordinary reality of the working world, couldhardly have conceived.For most of his tenure at General Motors, Walter Chrysler was able to workaround the chaos created by Durant’s management style and accomplish a great dealprecisely because of his nuts-and-bolts, take-charge approach to problem solving. Forexample, in the fall of 1917, after the United States had entered the First World War,Chrysler went to Durant’s office in New York to discuss possible war contracts with him.The waiting room was so full of hangers-on that Chrysler decided instead to go directlyto Washington, D.C., to the office of Colonel Edward Deeds, who was in charge ofaircraft production for the U.S. government. Within three hours, Chrysler emerged with acontract for 3,000 Liberty engines for airplanes and a roll of blueprints. Two weekslater, Chrysler’s Buick manufacturing staff, headed by master mechanic K. T. Keller,had completed the tooling needed to start production. The deal was done, signed,sealed and delivered before Durant had a clue as to what was going on.The inevitable split between Chrysler and Durant finally occurred in the summerof 1919. Walter Chrysler was about to sign a contract with the A. O. Smith Company ofMilwaukee, Wisconsin, to supply Buick with all of its frames over a five-year period, anarrangement that would save General Motors about $2 million a year. Although Durantwas kept fully informed about this contract, he nevertheless sent a telegram to a FlintChamber of Commerce luncheon announcing that Buick was going to build a $6 millionframe plant in Flint. Chrysler, who was at the luncheon meeting, stood up andannounced that this would never happen while he was at General Motors. He andDurant fought openly at the GM board of directors meeting the next day. Chryslerargued that not only would purchasing the frames be cheaper, it would represent nocapital cost for GM and required no addition to Flint\'s crowded workforce andinadequate housing supply. Durant could not say the same for his plan. Thedisagreements between the two only got larger and more bitter in the weeks to come.Chrysler opposed Durant’s decisions to buy a tractor company in Janesville, Wisconsin,and to build the $20 million General Motors Building in Detroit.Walter Chrysler soon announced his decision to quit GM and stuck to his guns,despite numerous efforts by several GM directors to get him to change his mind. Heresigned effective October 31, 1919. For all the contentiousness of Chrysler and

12Durant’s working relationship, the two men would remain lifelong friends. In 1939, Durantbegan writing an autobiography that he never finished. Durant dedicated his manuscriptto “Walter P. Chrysler, the best friend I ever had” and several other people, includingCharles S. Mott and Alfred Sloan, Jr. Chrysler reportedly wept when he read thededication.Once he left General Motors, Walter Chrysler was anxious to sell off hissubstantial holdings of GM stock. During his years as Buick president, Chrysler drew anannual salary of $500,000, but only $120,000 of that was in cash and the remaining$380,000 was in stock. Because the stock had gone up during the time Chrysler held it,the value was much greater than the purchase price of $1.14 million. Early in 1920, BillyDurant offered Chrysler $10 million for his stock, and he accepted the offer, even thoughthe market value of the shares was even higher. Chrysler was grateful to Durant for hispast generosity. The former machine shop sweeper left General Motors at age 44 with$10 million in cash, at a time when $1 million was still real money even to automobileexecutives.Flint’s major professional and business groups — the Rotary, Kiwanis andExchange Clubs — hosted a testimonial dinner for Walter Chrysler at the Flint CountryClub on January 22, 1920. Various community and business leaders offeredtestimonials to this man who had become an important community leader as well asbusinessman. Among those praising him were Charles Stewart Mott representingGeneral Motors and John North Willys from the Willys-Overland Company. The FlintWeekly Review, a labor newspaper, published a lengthy tribute written by the ReverendJ. Bradford Pengelly, pastor of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Flint and a close friend ofWalter Chrysler. Pengelly praised Chrysler for his fair treatment of all of his employeesand his efforts to provide them with adequate housing, medical care and social services.In ending his tribute, Pengelly said of Chrysler:He is a big, honest, human-hearted man who has worked up from the ranksto the management of one of the biggest factories in the U.S.A. He hasnever forgotten that he was once a private and has never put on airs of ageneral or a grand mogul. He is as honest as the day is long, and as squareas can be. I would take his word as quickly as his bond.The article struck an important chord in Chrysler’s story. As Vincent Curcio,

13Walter Chrysler’s biographer, has noted, Chrysler alone among the major figureswho built the automobile industry had firsthand experience with every aspect ofan industrial worker’s life. For the first 30 years of his life, he was basically ablue-collar mechanic, and he understood the day-to-day realities of workingmen, the “cold, hunger, penury, and the vagabond existence when the work ranout.” That Chrysler knew the nature of work as well as the science of machineryexplains his success at ALCO and Buick as much as his outsized personality —his seething ambition, his intellectual drive and his knack for the mechanical.Clearly Chrysler never stopped learning from experience, and because healways put what he learned to work elsewhere, perhaps the direction his careertook next should come as no surprise.Following his departure from General Motors, Walter Chrysler maintained anoffice in Detroit and went there every day from Flint. He threatened to retire at age 44 butdrove his wife Della to distraction with a constant stream of visitors to their Flint home.Sometime in late 1919, his old banker friend Ralph Van Vechten, who had financedChrysler’s purchase of the Locomobile in 1908, came to Walter with an interestingproposition. He wanted him to take over the management of the Willys-OverlandCompany to save it from bankruptcy. Chrysler agreed to do so, but only under certainconditions. He would receive a two-year contract that would pay him $1 million a year; hecould live in New York City and manage Willys from its plant in Elizabeth, New Jersey;and he would be given the power to make any changes he felt were needed.By 1920, the man who had earned one dollar a day sweeping floors in the UnionPacific Railroad shops in Ellis, Kansas, had become a “million-dollar-a-year man” capableof rescuing bankrupt automobile companies — perhaps even of creating his own

Vintage Sewing Pattern Lot of 32+- 1940s-2020s Women's Men's Children's All Size $50.00

Honolulu HI Postcard RPPC Photo Hula Dancers Girls San Francisco CA 1940 Vintage $29.95

Vintage 1940s Gillette Aristocrats Safety Razor Gold Plated Wonderful Condition $85.00

Scenic Greetings from Phillipsport NY c1940 Vintage Postcard $7.99

C1940s Westport Connecticut The Red Barn Davega Restaurant Sign Vintage Postcard $39.98

Vintage 1940s Portraits $20.00

Auriesville NY-New York, Entrance to Auriesville Shrine, c1940 Vintage Postcard $7.99

Vintage 1940s Smiley Pig $485.00

|