|

On eBay Now...

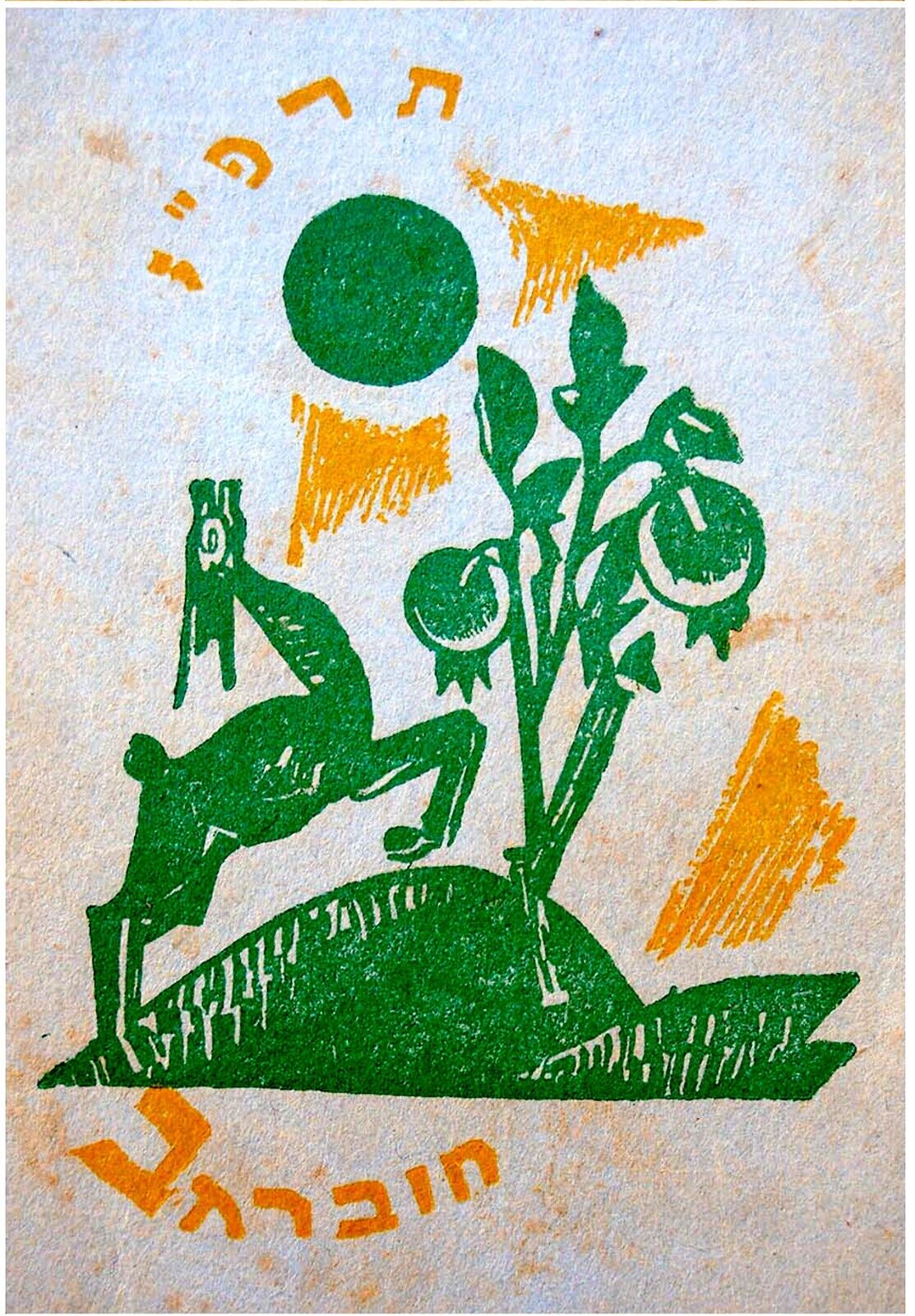

1926 Palestine HEBREW Israel RARE YOUTH MAGAZINE Jewish RUSSIAN AVANT GARDE For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1926 Palestine HEBREW Israel RARE YOUTH MAGAZINE Jewish RUSSIAN AVANT GARDE:

$110.00