|

On eBay Now...

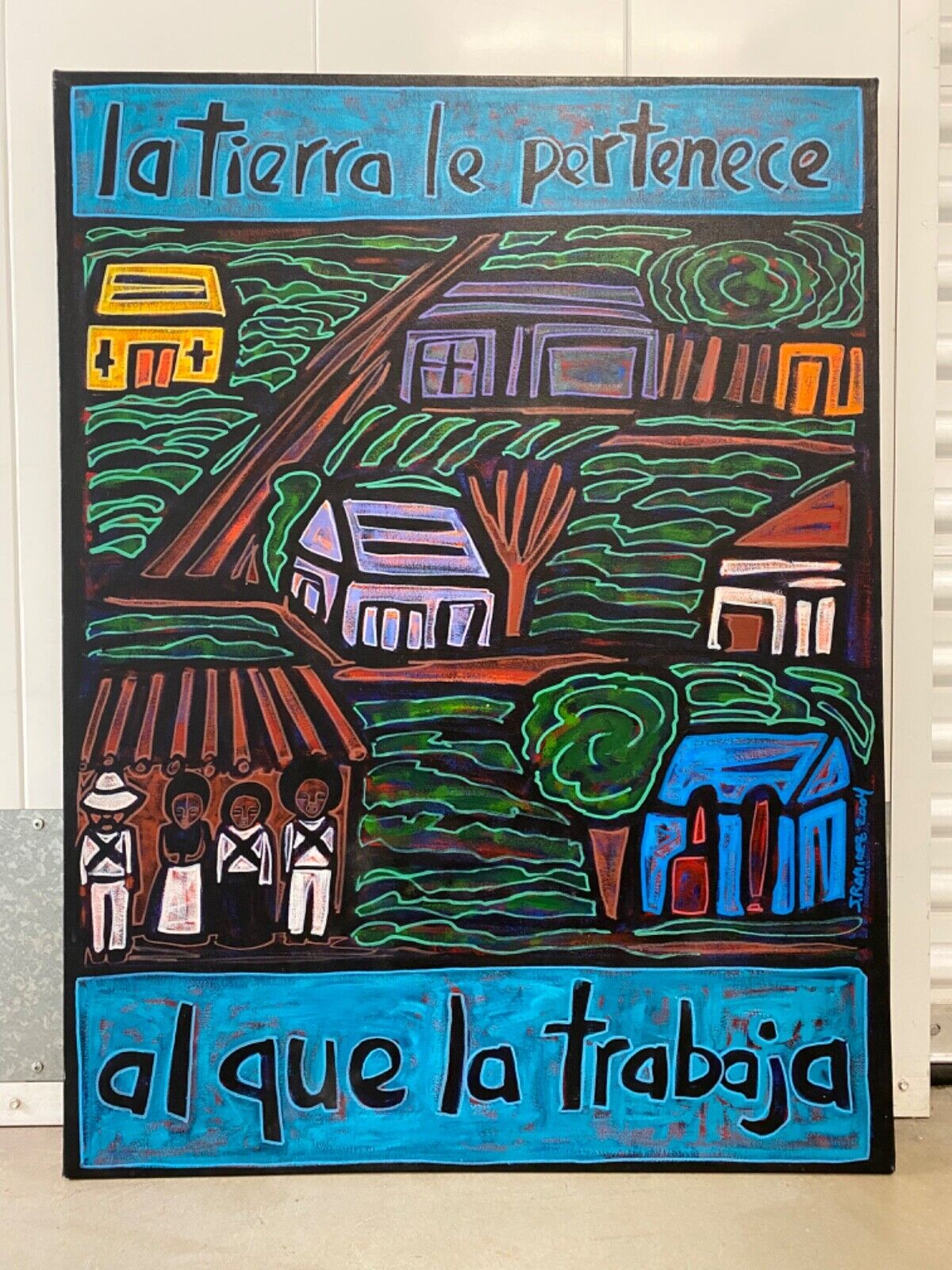

🔥 Important Mexican Modern Chicano Los Angeles Muralismo Painting, Jose Ramirez For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

🔥 Important Mexican Modern Chicano Los Angeles Muralismo Painting, Jose Ramirez:

$2750.00

This is an inspiring and powerfulImportant Mexican Modern Chicano Los Angeles Muralismo Painting, Acrylic on canvas, by celebrated Los Angeles Chicano Muralismo painter and activist, Jose Ramirez. This work depicts an agricultural field with small homes, rows of crops and trees, and a row of Mexican farm workers in the lower left corner. In bold letters, it reads on the top and bottom: "La tierra le pertence al que la trabaja," or in English, "The land belongs to one who works it." This message has roots in the early 20th century Mexican Zapatista movement, and as an inspiring philosophy behind the Farm Workers Movement of Mexican - American activist Cesar Chavez. This painting is rendered in bold, fluorescent colors which contrast against a stark black background, rendering the work a powerful aesthetic that can be recognized from afar. This is a hallmark of the Mexican muralist movement that found great visibility and influence in 20th century Los Angeles. Signed and dated at the lower right edge: "J. Ramirez 2004." This large piece is approximately 30 x 40 inches. Good condition, with some very minor scuffing and edge wear from storage (please see photos.) Acquired from an affluent collection in Los Angeles County, California. Jose Ramirez has been critically acclaimed and recognized throughout Southern California, and his works have graced book covers, public buildings, and museum galleries across the State. His originalpaintings are seldomly offered for sale, and never before on . Priced to sell. If you like what you see, I encourage you to make an Offer. Please check out my other listings for more wonderful and unique artworks!

About the Artist:

Jose Ramirez is an artist.In the past 30 years, he has illustrated children’s books, painted murals and completed commissions for numerous organizations and individuals. Ramirez is also an educator.He has taught in LAUSD for over 30 years (mostly 3rd grade) and is currently an Intervention Specialist at Esperanza Elementary in the Pico-Union neighborhood of Los Angeles. He received a BFA (1990) and an MFA (1993) in art from UC Berkeley.In 1995, he received a California Teaching Credential from CSULA.In 2001, he received the California Community Foundation Visual Artist Fellowship. He has worked with Altamed, National Immigration Law Center, Los Angeles Public Library, UCLA Center X, Childen’s Institute, Trejo’s Tacos, Glendale Community College, California Wellness Foundation, Inner City Struggle, Community Coalition and Self Help Graphics.His work was exhibited at the Mexican Cultural Institute in Washington DC, Plaza de la Raza, Avenue 50 Gallery in Highland Park and Homegirl Café in Los Angeles.His paintings were featured on the CBS TV show, The Good Fight.He is currently working on a children’s book titled ‘Mi papa es un agrícola/My Father is a Fieldworker’( Lil Libros) and a tile mural for the city of Los Angeles. He is the proud father of 3 daughters: Tonantzin, Luna and Sol.

ArtistJose Ramirezlives in El Sereno, Los Angeles. Through his paintings he "documents contemporary Latino life in Los Angeles by addressing socio-political conditions affecting that population." The following interview was conducted for In Motion Magazine by Roberto Flores, July 14, 2001. Abstract lines from pre-Columbian design Roberto Flores:In your early work, you used Aztec motifs as a background. How has your work evolved that you are not using those motifs as much? Jose Ramirez:My work has evolved in that it's branched out. Those motifs might be there in a not-in-your-face way. It's based in them. It's coming from them. And in some images, there's a lot of different directions that my work is taking. In some images it's more direct, and in others it's more subdued. The motifs might be on the walls of some of the images, if it's an interior image, or on the walls of the city -- stylized and abstracted. Originally, I was trying to do something that was more referential to a specific piece. Now, I've taken it in and it's coming out in a more stylized way. My work has evolved in that way. Roberto Flores:I see in your work different themes and takeoffs from those themes. For example, you might have the family theme, or the urban settings. The barrioscapes, I call them. In the barrioscapes themselves, what motivates you? Jose Ramirez:Different things. Sometimes it's a specific place that I go to a lot, or was part of me growing up. Other times, I want to show places that may be given a negative light by the media or people's impressions. I want to show the people in them, the colors in them, the connections with places. The colors, the images, the lines, the stylizations, the cars. Roberto Flores:What you are saying, I get on a visceral level. I get a good feeling. A beautiful place to live. The love, the colorfulness, the relationships, the simplicity of the place, and how this is a working-class neighborhood. A caring place. The mother holding the child. There's family, there’s love in this community. The colors are very warm - hot sometimes.Jose Ramirez:In a lot of them, I try to put the downtown skyline to reference that, to show the hierarchies. It’s far away. But real close to where I'm at, are the kids playing in the street, the adults walking or watching their kids. The colors. It’s all simplified. It’s been getting more and more simplified. Before,I would try to look at specific places and make them look, not photo realistic, but more realistic. Now It’s from here a lot of the times. Looking at a picture, but not continually looking at it to try and make it look the same. I feel more comfortable with my brush and what I'm trying to do, not creating just what the photograph looked like. I'm feeling more comfortable with being in the community where I work and where I live and grew up. Feeling more at ease. I was away for so long, studying. Now I have come back and I'm trying to find my place. I'm not necessarily saying that I have an idea of how It’s going to be done but I let it help mold me and then I offer it something. It’s a two-way play on that level. I try to reflect that in the paintings. We need to be here in our own places Roberto Flores:Obviously, Zapatismo has had a lot of influence in your work. Can you talk a little about where you think It’s taken you and how It’s impacted you? Jose Ramirez:I think It’s the philosophy behind Zapatismo which encourages. It’s not like past movements where things come from the top down. “This is what a true revolution is.” But the attitude of, “we are working together”, and “you have your set of issues, and they have their set of issues”. They can coincide but it doesn't have to be just for that community. It could be for your own community. The encouragement of that. Of seeing that on a global level. It’s not just “you've got to help the poor people in this country” but seeing that we are in a bad situation as well. We need to be here in our own places. This has helped me see It’s not just painting images of Zapatistas in Chiapas but seeing the possibilities in our communities by doing paintings like “The Comunidad” where It’s people in our community, with the people in their community, with historical references, trying to bring it all together.Also I see that the Zapatistas are part of a continuum from the ’60s, the Chicano Movement, back through pre-Columbian art. I see that as something new for an artist. It is something that inspires. Educated on a lot of different levels Roberto Flores:A couple of your paintings that I've seen portray young Black women that I'm assuming were your students. Jose Ramirez:Yes, when I taught in South Central. Roberto Flores:This had an impact on me, coming from a situation where I've seen Chicanos just focus in on Chicanos, and not really expand out and look at the interaction with other people. It was really refreshing. Jose Ramirez:I've been very privileged in that I got to be educated on a lot of different levels. Not at just a university level and a graduate level, but also in Mexico with my family, and with my grandparents. I've traveled and seen a lot of places. This has opened up my mind to know that it's not just about painting an Aztec image. It’s not just about painting Chicano images. Taking it all in, we are part of this whole continuum of history and art history. You can try to use those images or reinterpret a lot of the images and not feel like it's only got to be a nationalistic kind of thing. This goes in with Zapatista ideology. I dealt with this at Berkeley too -- the nationalists, the hard-core Mechistas. I fit in more with people who are trying to work across cultures and build coalitions. Chicano art is beautiful, but so is African art and African American art. I try to learn about all of that kind of art as well. Music, literature. Being exposed to it. Appreciating it. Roberto Flores:Yes, I thought it was really refreshing and beautiful to see a Chicano drawing on and about Blacks. Depicting them in such a dignified and beautiful way. I recently saw a video about Henry Sugimoto, the Japanese-American artist. He was interned during World War II. He was also influenced by Diego Rivera. He did some art relating to the campesino and that too was really refreshing. Jose Ramirez:It’s interesting because in the ’30s, ’40s and ’50s there was a whole generation of African American artists directly influenced by the muralists in Mexico. Some of them went down and lived in Mexico. You see it in some of the murals that were produced here by African American artists. There was an exhibit that went through the African American museum by USC that showed this history. It was about the Mexican muralists and African American artists. It showed both their works and their connections. Roberto Flores:It’s also very much in line with the spirit and thinking of Anthony Gleeton, the photographer who did a lot of work in Oaxaca, in Guerrero, where Blacks combined with the indigenous people. It’s very refreshing. La loteria I was going to ask you about La Loteria, your relatively recent use of La Loteria to put across different themes. I look at each one of those cards and I read a lot into them. Maybe I read too much into them, but the symbols you pick are not the regular Loteria symbols. They are very meaningful. Like the one “Ojo” which I think is a loteria symbol. Jose Ramirez:Yes, there have been a lot of different interpretations throughout history of la loteria. I think it's been around for 3 or 4 hundred years. I was given one of Jose Guadalupe Posada’s loteria images and was inspired, encouraged, by the art dealer who gave it to me, to do a series of loterias. I saw it and I saw that a hundred years ago this guy was doing these intense images for la loteria that could be put together in a political way. I thought, I've got to use these. When I started to do my own, I looked at my old paintings and I said I like a particular image, why don't I put it with this image, and this image, and I then picked an image from the old loteria and then they say something. I read into them a lot, as well. It’s been a lot of fun to put these paintings together with that in mind. Even three or five together in a certain way can say a lot about a specific incident or something in general. Reinventing my work every once and a while can lead to a new idea with something else. It grows that way in here - in my studio. Not trying to speak in an academic language all the time Roberto Flores:What you've been saying is that when you do art, you do it for everyone. Your audience is everyone. It’s not like when you are writing you have to think and delimit your audience and focus in on a sector of everyone. It seems to me when you do art you are trying to be broadly inclusive. You include children. The texture and the images and the strokes seem to me very much what children can do. Jose Ramirez:Yes. And also being very direct and not trying to speak in an academic language all the time. Although that's what I was encouraged to do when I was studying art. I learned it but then I was trying to find avenues to do something that was more direct and easier to access, that anybody can see. I have my reasons to paint and I want people to understand my art and not be turned off by art. You can walk into a museum and see something that you don't understand, then think that all museums are like that, or all art is like that. I would like to be able to have my work speak to people that aren't necessarily educated in the most current trends in art and know only that my work is responding to this work which is responding to that work. Although it is, and I know it, maybe someone else can see it and not necessarily have to see that to appreciate it. It’s frustrating when art only reflects something abstract or academic that people can't access. Roberto Flores:A very small portion of the population can relate to that. Ancestors In terms of ancestors, the Ancestor series, the feel for me is that it's something deep inside us to respect the elders, and ancestors, those that came before us. It isn't something that the youth are that conscious of, or practicing that much. But it can be awakened. Is that part of your effort with the ancestor series? Jose Ramirez:Yes, and to acknowledge that we have ancestors on a lot of different levels, not just several thousand years ago, but our grandparents or our parents. Our elders in the community. These things are not just ideas that I'm visualizing but also other artists in the community are putting them to music, or to word, or to their actions. These are ideas that are out there and I hear people talk about. DJ Fidel Rodriguez of Seditious Beats was talking about ancestors. Quetzal's music is influenced and is reflecting on music that ancestors did. And so is my art. I hope that people can connect with it. We are not encouraged to a lot of times but it's something that could be very powerful. Roberto Flores:One of the other things I see is ancestors are not only people who ... the transition, the cutoff line of being dead and being an ancestor and being alive is not there. It’s like you can be living and be an ancestor. Jose Ramirez:Yes. Roberto Flores:The transition is blurry. What I see in what you are saying is the way to build barrios, the way to build community, the way to reach some of these Zapatista goals, respect, starts at the family. Jose Ramirez:I think that, yes, but unfortunately that is not the reality for a lot of the students that I work with. Sometimes being in a family can be very disastrous in some ways too. My experiences with my family and the family that I'm trying to build now with my kids leads me to be proactive. I'm actively trying to involve my work -- to be more pro-active, more positive. I'm not saying that I don't comment on negative issues or do painting that could be called political, but rather than being complaining and negative all the time, which is stuff that you go through, a phase of protest, I'm trying to evolve my work into something that is more positive, proactive. Canvas, plywood and paper Roberto Flores:Your medium. You paint with oils on canvas but you also paint on plywood. Jose Ramirez:Acrylics on plywood. Sometimes paper. Before it was whatever I could find. Now It’s little bit more refined, or if I find wood then I'll do a lot of wood pieces. If I have canvas, then I'll make canvas paintings. But whatever I have around I work with. Roberto Flores:Is there a thing about making that accessible as well? Canvass you have to prepare, but a piece of plywood ... Jose Ramirez:... you can find out in the street. Roberto Flores:Find in the street. Jose Ramirez:Yes. And a lot of times people who look at the work love that it's on plywood. They like that it has a big old gash going across it because they can see that it has its own history. And other times people are taken aback and they can't take it seriously. They are afraid to respect it as art because they think it's not taken seriously. Nic Paget-Clarke:I've seen a couple of your earlier works and they are black and white, grays, but the majority of your work is bursting with color. I'm wondering how that came about. Jose Ramirez:I think a big part of that is just getting better with paint, practicing. I try to paint a lot and to be conscious. As I said before, I would try to paint something that looked like something in a photograph. Now I have gotten away from that and I go straight into working with that flat piece and make that colorful. It’s more relaxing for me to focus on that. My work is more stylized. Roberto Flores:Do you think you'll ever do other earlier works, like the chalk Rodney King piece, in color? Jose Ramirez:I look back at my portfolio when I'm not sure what to do, what to work with next. And when I look back and I see something that I like I try to reinterpret it with color. This is what I did with the Notevejes piece. I had done that as a charcoal drawing five years ago then I did it in paint five years later with color. It evolved. I go back to some images and reinterpret them. So yes I would. I'm not closed to doing stuff like that, to having a wide range of things that I could do. For example, the show that I hung today in Long Beach has some pieces that could be considered angry or protest, but then there are others that are calm and serene and nice to look at. I think that that is OK to do. We are complex people. We are not just one-minded. We can think a lot of different thoughts. Just as musicians can do different things with music, artists can do different kinds of paintings.

Published in In Motion Magazine August 25, 2001.

JOSE RAMIREZA Short History of Los Angeles

Mural

2019

A Short History of Los Angeles is a large-scale artwork by artist Jose Ramirez. Ramirez’s densely packed Los Angeles cityscape unearths the hidden histories and natural foundations of our community. The modern L.A. skyline towers above an underground scene of old Los Angeles - Longhorns, oil towers, citrus farms, and Cenozoic mammals wander alongside migrants, fences, rivers, and oak trees. Ramirez’s image questions what exactly grounds (and is erased by) the built world and calls us to acknowledge the symbiosis of the natural and urban. It is also a call to remember the evolution of Los Angeles, and the complex social and political forces that shape our everyday environs.

Longstanding Chicano artist Jose Ramirez is using his art to start a dialogue around social change. This weekend his studio is open to all.Growing up in East Los Angeles in the ‘70s, Jose Ramirez would drive around his neighborhood and see the endless sprawl of Chicano murals covering the streets of his community. When he visited his family in Jalisco, Mexico during the summer, he watched as his uncles painted their own canvases. Little did he know at the time thatChicano art would become his life’s work. The bright colors. Dark lines. Social justice messages. Ramirez says he identified with the murals in El Sereno and Lincoln Heights during a time when he didn’t see Mexican-Americans like him reflected in the news or on TV shows. “We would see each other as criminals or house cleaners, not as people in positions of power,” Ramirez says. “The Chicano movement was really important in bringing these issues to light. It was important in making us present because, otherwise, we wouldn’t have been around.” In ninth grade, Ramirez received a scholarship to attend Verde Valley, a boarding school in Sedona, Arizona. He was recruited at his middle school in El Sereno through a program called A Better Chance, which aims to diversify private schools across the country. It was at Verde Valley that Ramirez took his first art class. And he pursued the arts throughout high school, taking photography, ceramics and drawing courses. “I was excited to leave home, but it was nothing like what I expected it to be,” he says. “It was very white, a lot of wealthy kids, small too. I was really quiet and I wasn’t very academically prepared for it. It was good that I had art. A good way for me to come to terms with where I was and understand it, a way to document what I was experiencing at school.” After graduating high school, Ramirez started college at UC Berkeley in 1985. He focused on ceramics and sculpting during his undergraduate years, working at a studio established by internationally renowned ceramicist Peter Voulkos. It wasn’t until Ramirez returned to graduate school at Berkeley in 1991 that he had more of a direction for his art and was challenged for what he was doing with it. “When I went back, I knew I was a Chicano artist,” he says. “I knew that I was going to be working more with clay but still painting. But in the early ‘90s, a lot of the professors I had in the graduate program were mostly white … and they didn’t really understand Chicano art. They didn’t know how to talk to me about my art, so their reaction was: ‘We don’t understand this.’ ‘We don’t know what you’re doing.’ ‘It looks scary.’ ‘It looks like the work of a serial killer.’ ‘It’s too Mexican.’” Instead of changing his work to please his professors, Ramirez sought out allies in visiting artists like Chicano poet Jose Montoya and Chicana muralist Juana Alicia. “They put my work into context and helped me understand that my audience was not an academic elite, ivory tower type of art,” Ramirez says. “My art was going to be valued somewhere else, it had a higher calling than just staying in that art department.” After receiving his MFA in art in 1993, Ramirez moved back to Los Angeles and started exhibiting his work.Deeply rooted in his Mexican-American heritage,his paintings feature humble workers, teachers, children and ancient warriors often surrounded by the metropolitan fabric of Los Angeles. He begins with modest line drawings and slowly builds up to bright primary colors and dark black lines for contrast. Over the years, he’s exhibited at the Los Angeles Central Library, the Mexican Cultural Institute in Washington, D.C., Avenue 50 Gallery in Highland Park and Homegirl Café in Los Angeles. He also received his teaching credentials in 1995 from Cal State L.A. and started teaching in South Central, eventually transferring to Esperanza Elementary School in Pico-Union, where he’s been for the past 20 years. He’s currently teaching third grade. “When I see my students, I see myself because I’m a product of L.A. Unified,” he says. His students fuel much of the social justice messaging in his art. “I’m a school teacher in Pico-Union, which is a very marginalized community with a lot of immigrants,” he says. “Last year, I had six immigrant students from Central America. They’re all from that neighborhood, so I hear and I see and I work with the students, and I hear what they go through, so sometimes those stories make their way into my paintings.” This year, Ramirez released a collection of paintings inspired by his teaching experiences. They showed protesters holding signs bearing messages like “Invest in Public Education” and “Kids First!” Ramirez says the work coming out of the East L.A. community centers Self Help Graphics and Plaza de la Raza — both cornerstones in L.A.’s Mexican American art community — inspire him as well. And his experiences living in Boyle Heights as a wave of gentrification sweeps the area naturally make their way into his art. “I always want East L.A. to be central to my work because I’m so close to it,” Ramirez says. “I see that it’s really hard for people to find affordable housing … a lot of people who made this neighborhood what it is are getting pushed out. And people who are moving in don’t understand what was here before and appear to have no desire to really respect or think about that. There’s a lot that’s getting lost and it’s happening at a really fast pace.” Ramirez is currently working on ideas for a children’s book based on the history of Boyle Heights — and it will no doubt have his signature vibrant Chicano style. “If I can get someone who’s not your average person who looks for art to stop and look and maybe be attracted by the bright colors and then look closer and see a new perspective about what’s happening in the world, then I’ve done my job,” Ramirez says. “Art has power to change things.”

On Art, Education, and Gardens: an Interview with Jose Ramirez

Jose Ramirez is an artist, educator, and father rooted in Los Angeles. His art pieces can be seen everywhere, from the homes of family and friends in the form of calendars and illustrated children’s books to the murals in Trejo’s Cantina in Hollywood. I first met Ramirez through his youngest daughter, Sol, who I quickly became friends with through Self Help Graphics’ Youth Committee about two years ago. Through Sol, I was able to interview Ramirez and learn further about him, his art, and even his garden. Ramirez currently lives in Los Angeles and has lived here his entire life with the exception of the ten years he spent attending high school and college. Ramirez attended the University of California Berkeley where he received both his Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Art. Following his time at Berkley, he received his teaching credentials from California State University, Los Angeles. When I asked about what first drew him to art, Ramirez shared that his art teacher’s response and guidance fostered his love of art. This responsiveness from his teacher, in addition to the healing qualities art posed for him at the time, led him to explore art further and increase his interest. Ramirez shared that his favorite art mediums to work with are acrylic and enamel, both of which he uses frequently in his pieces. In addition to being an artist and father, Ramirez is also an educator. At the moment, he works at Esperanza Elementary as an Intervention Specialist. He speaks about his past and current students highly, sharing that alongside his children and his artwork, an accomplishment which he feels quite proud of is his students. He also shares that the students, parents, and the relationships he has with the communities that he teaches are his greatest inspiration. Being an artist has impacted his teaching career in a positive manner; by living life through the lens of an artist, he shared he is able to be a better teacher. Ramirez shares advice on navigating the art world through trial and error and how critical mistakes are to the livelihood of success. He discussed that, while learning to navigate the art world, he learned that communication is essential in order to lay boundaries as to what you are willing and able to do. Additionally, he recommends worrying less about the art world (the critics and whatnot) and focusing more on making good art. On top of everything Ramirez manages to do, he also maintains a beautiful garden that includes an extensive range of plants from fruit trees to maize. Ramirez shared that three things that best represent him would be trees, schools, and music.

City Council Recognizes Local Artist | Jose B. Ramirez HonoredSouth Pasadena Mayor Dr. Marina Khubesrian recognized the artist for displaying his pieces of artwork in the City Hall Gallery

Artist José B. Ramirez was recently recognized by the South Pasadena City Council for displaying his artwork in the front entrance at City Hall. The paintings inspire Ramirez’s interest in the role of soil biology and history in human survival. “My paintings are figurative, urban, and Chicano. They combine references to resistance and struggle to provide a context for understanding the contemporary issues we face,” said Ramirez on his website. “I try to comment on these struggles while visualizing the hopes and dreams of our community. I want my work to speak a language that is easy to access. Ramírez was born and raised in East Los Angeles and later attended the University of California, Berkeley where he earned his B.F.A. in 1990 and his M.F.A. in 1993. His pieces of art will be on display through the end of March at City Hall. Ramírez received his teaching credentials from California State University, Los Angeles in 1995 and has worked as an elementary school teacher for nearly a decade, currently teaching third grade. He has exhibited widely throughout the country including a one-person exhibition at UFA Gallery in New York, and his work can be found in many private collections. In addition to gallery exhibitions, Ramírez has completed numerous public art projects including murals for the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, Dolores Mission Church, and Ascot Avenue Elementary School. “It’s an honor to show my work in the city,” said Ramirez upon receipt of the certificate of appreciation. “Thank you very much.” Council member Diana Mahmud praised his artwork, saying, “They’re beautiful,” before fellow Council member Robert Joe said Ramirez’s work “…was fantastic. It has really opened our eyes in City Hall with your work. I really appreciate what you have done.” - Bill Glazier

Spotlight on artist and educator, José Ramírez

One of the great joys of publishing a book is having some say in the art that is chosen to adorn its cover. I have been blessed to be published by presses that have listened and considered my suggestions.

In 2009, Bilingual Press published my short-story collection,Anywhere But L.A.The press showed me several pieces of art to consider, and the one I chose was by Los Angeles-based artist, José Ramírez.

After many years of attempting to meet José, I finally had a chance to visit his home and studio because my wife and I desperately wanted to buy a painting or print by Joséfor our new home.We were not disappointed. We got to meet his wife, mother-in-law, and one of his three daughters. They are all accomplished in their own way.

After a great visit where we learned that we might be related (we both have family from Ocotlán in Jalisco, and I have family named Ramírez), my wife and I purchased a beautiful, signed print.

José earned his BFA (1990)and MFA (1993)from UC Berkeley and teaches third grade at Esperanza Elementary in the Pico-Union neighborhood of Los Angeles (not far from where I grew up). In 1995, he received a California Teaching Credential fromCal StateUniversity, Los Angeles.

Joséhas illustrated children’s books, painted murals, and completed commissions for numerous organizations and individuals.

IMPORTANT Medallion Antiquity Classical Greek PB Medallion Zeus & Hercules wCOA $829.17

Calvin Coolidge and Important People, Plymouth , VT, 1924, Real Photo Postcard $35.00

Important Master Carver Robert Whonnock Hawk Bowl Kwakiutl Kwakwaka'wakw $1105.00

Important Unitarian Minister Supported Chinese Immigrants, Embarrassed Opponent $145.00

The Principles of Jewish Law by Menachem Elon IMPORTANT CLASSIC $34.65

Important Extensive WHALING Industry Collection Postcards, Photos, Stamps, cards $312.14

Important Bottle Islamic Ottaman Arabic Syria Copper $278.49

Large Lot of Antique Beans Identify Various Era Miniature Cookie $427.53

|