|

On eBay Now...

\"4th Earl Stanhope\" Philip Henry Stanhope Signed Free Frank For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

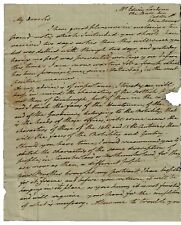

\"4th Earl Stanhope\" Philip Henry Stanhope Signed Free Frank:

$399.99

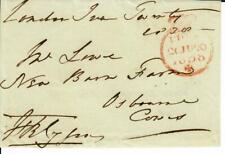

Up for sale a RARE! "4th Earl Stanhope" Philip Henry Stanhope Hand Signed Free Frank.

ES-6344E Philip Henry Stanhope, 4th Earl Stanhope FRS (7 December 1781 – 2 March 1855), was an English aristocrat, chiefly remembered for his role in the Kaspar Hauser case during the 1830s. He was the eldest son and heir of Charles Stanhope, 3rd Earl Stanhope (1753–1816), by his second wife Louisa Grenville (1758–1829), daughter and sole heiress of the Hon. Henry Grenville, Governor of Barbados in 1746 and ambassador to the Ottoman Porte in 1762, a younger brother of Richard 1st Duke of Buckingham and Chandos. Using his father's courtesy title Viscount Mahon, he served as a Whig Member 1806 to 1807, for Kingston upon Hull from 1807 to 1812, and for Midhurst from 1812 until his succession to the peerage on 15 December 1816, when he took his seat in the House of Lords. He shared his father's scientific interests and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society on 8 January 1807 and was a president of the Medico-Botanical Society. He was a vice-president of the Society of Arts. Like other members of his gifted family, notably his half-sister Lady Hester Stanhope, he is usually portrayed as a somewhat eccentric character. Having studied in Germany, he travelled extensively in Europe (mostly alone, though he was married and had a son and a daughter), which brought him into contact with various princely courts and which caused him great expenditure. In contrast to some accounts, which suggest that he lived beyond his means, it appears that he remained wealthy, certainly after he had succeeded to his father's estates in 1816. His eccentricity may be understandable since, as his daughter the Duchess of Cleveland wrote in her Life and Letters of Lady Hester Stanhope, his own father refused to send him to school but kept him at the family home of Chevening. The plan was that Philip would agree to his father's terminating the entail on the estates. The biography implies that the Earl would then have sold the estates and sent the money overseas, impoverishing his family. Hester helped her brother escape and her letters, quoted in the Life, record that William Pitt the Younger and others rejoiced over what she had done. Stanhope became interested in the story of the "foundling" (aka a "feral child") Kaspar Hauser, a youth who had appeared in Nuremberg in 1828 and had become famous through his claim that he had been raised in total isolation in a dark room and could tell nothing about his identity. Furthermore, Hauser was found with a cut wound in 1829 and claimed to have been attacked by a hooded man. This led to various rumours that he might be of princely parentage but also suspicions that he was an impostor. Stanhope first met Hauser in 1831 and soon felt a strong affection for the young man: indeed, their relationship could as contemporary rumours suggested. He endowed him generously and paid for (unavailing) inquiries in Hungary to clarify the young man's origin, as the latter, in 1830, had claimed to remember had led to speculations that he might originate from there. Hauser's custodian, Baron von Tucher, criticised Stanhope's pedagogically wrong behaviour towards Hauser and retired from his custodianship. Now Stanhope, in December 1831, became Hauser's foster-father and transferred him to the care of a schoolmaster. In January 1832, he returned to England from where he continued to communicate by letter with his fosterling and also with officials examining the case. Stanhope had favoured the theory that Hauser stemmed from Hungarian magnates but had to give up this idea when he was informed that further inquiries in Hungary had, once more, failed completely. In a letter to the Bavarian court president Anselm von Feuerbach (dated 5 October 1832), Stanhope now clearly uttered his doubts in Hauser's credibility. While he continued to pay for his fosterling's living expenses, he never made good on his promise that he would take him to England and his letters to Hauser became less affectionate. Hauser did realise this change of mood. On 14 December 1833, Hauser came home with a deep wound in his chest and claimed to have been stabbed by a stranger. He died three days later. Although Stanhope had long stopped believing in Hauser's tales, he at first was of opinion that Hauser had indeed been murdered, a view he uttered in one of his letters (dated 28 December). In another letter from 7 January 1834, when he had received more information on what had happened, a change of mind announces itself: he would later advocate the position that Hauser himself had inflicted the wound by pressure, and that, after he had squeezed the point of the knife through his wadded coat, it had penetrated much deeper than he had intended. In his Tracts Relating to Caspar Hauser (1836, German original: 1835) Stanhope published all known evidence against Hauser: The more I was deceived in this affair, and the more erroneous were my views, the more is it now my duty to act with zeal, and, if it were in my power, with ability, to preserve others as far as possible from similar errors. Though I have on that account appeared in an unfavourable light to some of those who are known or unknown to me, though I have been abused and even calumniated, I find a sufficient consolation in my own conscience. Stanhope, indeed, was attacked by followers of Hauser, and even accused of contriving his death. They suggested that Hauser was a hereditary prince of Baden and was murdered for political reasons. Some professional historians (such as Ivo Striedinger) defended Lord Stanhope as a "seeker of truth" and as a deceived philanthropist who had realised his delusion. Anthroposophist author Johannes Mayer, however, substantiated the accusations against Stanhope in a major biographical study of him and showed that he was in fact a British political agent working for the House of Baden against Kaspar Hauser.

RARE “4th Earl Beauchamp" Henry Lygon Signed Free Frank Dated 1838 $499.99

William Francis HARE, 4th Earl of Listowel / Signature Signed $36.00

"4th Earl of Dartmouth" William Legge Clipped Signature $99.99

ESC Company: Charles McClenning; July 4th, Earl the Eagle, Item# 24194 $59.99

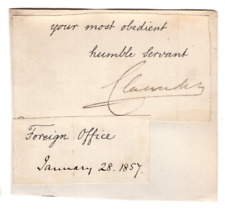

George Villiers, 4th Earl of Clarendon Signed Clip 1857 / Autographed $17.99

George Charles Herbert, 4th Earl of Powis Signed Letter 1895 / Autographed $18.99

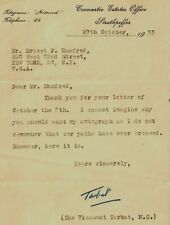

RARE "4th Earl of Cromartie" Roderick MacKenzie Hand Signed TLS Dated 1953 COA $199.99

"4th Earl of Bradford" George Bridgeman Hand Written Letter COA $499.99

|