|

On eBay Now...

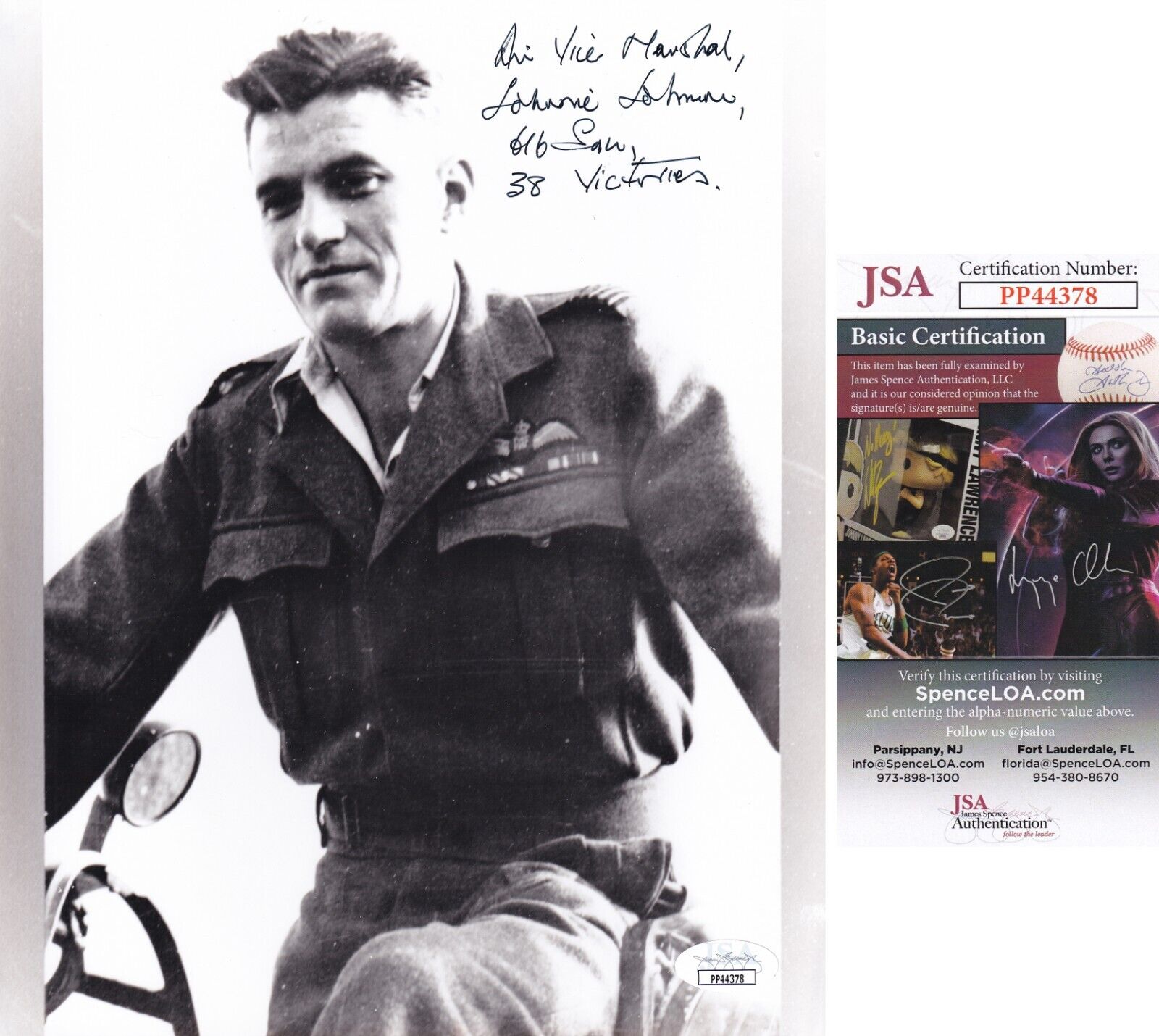

WWII RAF Ace 38 Vic. James \"Johnnie\" Johnson Battle of Britain SIGNED JSA 8x10 For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

WWII RAF Ace 38 Vic. James \"Johnnie\" Johnson Battle of Britain SIGNED JSA 8x10:

$249.99

READ HIS BIO ONEOF THE MOST REMARKABLE MILITARY CAREERS. Thissale is for the following James \"Johnnie\" Johnson (Deceased) WWIIRAF Ace Pilot 38 Victories, Battle of Britain autographed 8x10 photograph thatis JSA authenticated #PP44378. This James \"Johnnie\" Johnson autographed8x10 has been authenticated by the most prestigious and respectedauthentication company in the hobby JSA. Autographed items that have beenauthenticated by JSA adds an additional value to all signed items that bare theJSA authentication process. BIO: James \"Johnnie\"Johnson (Deceased) WWII RAF Ace Pilot 38 Victories, Battle of Britain nicknamed\"Johnnie\" was an English Royal Air Force (RAF) pilot and flying acewho flew and fought during the WWII. Johnsonwas credited with 38 individual victories over enemy aircraft, as well as sevenshared victories, three shared probable, ten damaged, three shared damaged andone destroyed on the ground. Johnson flew 700 operational sorties and engagedenemy aircraft on 57 occasions. Included in his list of individual victorieswere 14 Messerschmitt Bf 109s and 20 Focke-Wulf Fw 190s destroyed making himthe most successful RAF ace against the Fw 190. This score made him the highestscoring Western Allied fighter ace against the German Luftwaffe. Johnsongrew up and was educated in the East Midlands, where he qualified as anengineer. A sportsman, Johnson broke his collarbone while playing rugby, aninjury that later complicated his ambitions of becoming a fighter pilot.Johnson had been interested in aviation since his youth and applied to join theRAF. He was initially rejected, first on social, and then on medical grounds;he was eventually accepted in August 1939. The injury problems, however,returned during his early training and flying career, resulting in him missingthe Battle of France and the Battle of Britain between May and October 1940. In1940 Johnson had an operation to reset his collarbone, and began flyingregularly. He took part in the offensive sweeps over German-occupied Europefrom 1941 to 1944, almost without rest. Johnson was involved in heavy aerialfighting during this period. His combat tour included participation in theDieppe Raid, Combined Bomber Offensive, Battle of Normandy, Operation MarketGarden, the Battle of the Bulge and the Western Allied invasion of Germany.Johnson progressed to the rank of group captain by the end of the war. Johnsoncontinued his career in the RAF after the war, and served in the Korean Warbefore retiring in 1966 with the rank of air vice marshal. He maintained aninterest in aviation and did public speaking on the subject as well as enteringinto the business of aviation art. Johnnie Johnson remained active until hisdeath in 2001. Joining the RAF: Johnsonstarted taking flying lessons at his own expense. He applied to join theAuxiliary Air Force (AAF) but encountered some of the social problems that wererife in British society. Johnson felt he was rejected on the grounds of hisclass status. Johnson\'s fortunes were to improve. The prospect of war increasedin the aftermath of the Munich Crisis, and the criteria for applicants changedas the RAF expanded and brought in men from ordinary social backgrounds.Johnson re-applied to the AAF. He was informed that sufficient pilots werealready available but there were some vacancies in the balloon squadrons.Johnson rejected the offer. Inspiredby some Chingford friends who had joined, Johnson applied again to join theRoyal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR). The RAFVR was a means to enter theRAF for young men with ordinary backgrounds. All volunteer aircrew were madesergeant on joining with the possibility of a commission. Once again he wasrejected, this time on the grounds that there were too many applicants forvacancies and his injury made him unsuitable for flight operations. Hisambition frustrated, Johnson joined the Leicestershire Yeomanry, where theinjury was not a bar to recruitment. He joined the Territorial Army unitbecause, though he was in a reserved occupation, if war came, he had \"nointention of seeing out the duration building air raid shelters or supervisingdecontamination squads\". Johnson was content in the Yeomanry. One daywhile riding through Burghley, near Stamford, on annual camp Johnson took adetour to RAF Wittering nearby (now in Cambridgeshire.) Upon seeing a line ofHawker Hurricane fighters Johnson remarked \"If I\'ve got to fight HitlerI\'d sooner fight him in one of those than on a bloody great horse!\". Flight Training: InAugust 1939, Johnson was finally accepted by the RAFVR and began training atweekends at the airfield Stapleford Tawney, a satellite airfield of RAF NorthWeald. There he received ground instruction on airmanship.[19] Taught byretired service pilots of 21 Elementary & Reserve Flying Training School,Johnson trained on the de Havilland Tiger Moth biplane. Upon the outbreak ofwar in September 1939, with the rank of sergeant, Johnson entrained forCambridge. He arrived at the 2nd Initial Training Wing to begin flightinstruction. He was interviewed by senior officers in which he said hisprofession and knowledge of topography, surveying and mapping would make himmore useful in a reconnaissance role. The wing commander agreed, butnonetheless, Johnson was selected for fighter pilot training and given theservice number 754750 with the rank of sergeant. Johnson and several hundredothers were entrained for Cambridge and the 2 initial Training Wing. Whileassigned here Johnson learned basic military drill, sometimes given the slangname \"square bashing\". ByDecember 1939, Johnson began his initial training at 22 EFTS (Elementary FlyingTraining School), Cambridge. He flew only three times in December 1939 andeight in January 1940, all as second pilot. On 29 February 1940, Johnson flewsolo for the first time in Tiger Moth N6635. On 15 March and 24 April, hepassed a 50-minute flight test followed by two night flights the following day.The chief flying instructor passed him on 6 May. He then moved to 5 FTS atSealand before completing training at 7 OTU (Operational Training Unit) – RAFHawarden in Wales flying the Miles Master N7454 where he earned his instrument,navigation, night-flying ratings and practised forced landings. After trainingwas complete on 7 August 1940, Johnson received his \"wings\" and wasimmediately inducted into the General Duties Branch of the RAF as a pilotofficer with 55 hours and 5 minutes solo flying. On19 August 1940, Johnson flew a Spitfire for the first time. Over the next weekshe practised handling, formation flying, attacks, battle climbs, aerobatics anddogfighting. During his training flights, he stalled and crashed a Spitfire.Johnson had his harness straps on too loose, and wrenched his shoulders –revealing that his earlier rugby injury had not healed properly. The Spitfiredid a ground loop, ripping off one of the undercarriage legs and forcing theother up through the port main plane. The commanding officer (CO) excusedJohnson, for the short airfield was difficult to land on for an inexperiencedpilot. Johnson got the impression, however, that he would be watched closely,and felt that if he made another mistake, he would be \"certainly washedout\".[24] Johnson tried to pack the injured shoulder with wool, held inplace by adhesive tape. He also tightened the straps to reduce vibrations whileflying. The measures proved useless and Johnson found he had lost feeling inhis right hand. When he dived the pressure aggravated his shoulder. He oftentried to fly using his left hand only, but Spitfires had to be handled withboth hands during anything other than simple manoeuvres. Despite thedifficulties with his injuries, on 28 August 1940, the course was complete.Johnson had 205.25 hours on operational types including 23.50 on the Spitfire. Aftertraining, in August 1940, he was briefly posted to No. 19 Squadron as aprobationary pilot officer. Due to equipment difficulties, 19 Squadron wereunable to complete Johnson\'s training and he left the unit. On 6 September 1940Johnson was posted to No. 616 Squadron at RAF Coltishall. Squadron Leader H.L\"Billy\" Burton took Johnson on a 50-minute training flight in X4055.After the flight Burton impressed upon Johnson the difficulties of deflectionshooting and the technique of a killing shot from line-astern or nearline-astern positions; the duty of the number two whose job was not to shootdown enemy aircraft but to ensure the leader\'s tail was safe. Burton alsodirected Johnson to some critical tactical essentials; the importance ofkeeping good battle formation and the tactical use of sun, cloud and height. Fivedays later, Johnson flew an X-Raid patrol in Spitfire X4330, qualifying for theBattle of Britain clasp. Johnson\'s old injury continued to trouble him and hefound flying high performance aircraft like the Spitfire extremely painful. RAFmedics gave him two options; he could have an operation that would correct theproblem, but this meant he would miss the Battle of Britain, or becoming atraining instructor flying the light Tiger Moth. Johnson opted for theoperation. He had hoped for discreet treatment, but word soon reached the CO,and Johnson was taken off flying duties and sent to the RAF hospital atRauceby. He did not return to the squadron until 28 December 1940. CO Burtontook Johnson up for a test flight on 31 December 1940 in Miles Magister L8151.After the 45-minute flight, Johnson\'s fitness to fly was approved. WWII: Johnsonreturned to operational flying in early 1941 in 616 Squadron, which was formingpart of the Tangmere Wing. Johnson often found himself flying alongside WingCommander Douglas Bader and Australian ace Tony Gaze. On 15 January 1941,Johnson, the recently appointed Squadron Leader Burton and Pilot Officer HughDundas, who arrived back at the squadron on 13 September 1940, took off tooffer cover for a convoy off North Cotes. The controller vectored the pair ontoan enemy aircraft, a Dornier Do 17. Both attacked the bomber and lost sight ofit and each other. Although the controllers intercepted distress signals fromthe bomber Johnson did not see it crash. They were credited with one enemyaircraft damaged. It was the only time Johnson was to engage a German bomber.By the end of January, Johnson had added another 16.35 flying hours onSpitfires. Inthe opening months, Johnson flew as a night fighter pilot. Using day fightersto act as night fighters without radar was largely unsuccessful in interceptingGerman bombers during the Blitz; Johnson\'s only action occurred on 22 February1941 when he damaged a Messerschmitt Bf 110 in Spitfire R6611, QJ-F. A weeklater, Johnson\'s squadron was moved to RAF Tangmere on the Channel coast. Johnsonwas eager to see combat after just 10.40 operational hours and welcomed theprospect of meeting the enemy from Tangmere. If the Germans did not resumetheir assault the wing was to take the fight to them. InNovember 1940 Air Marshal Sholto Douglas became Air Officer Commanding (AOC)RAF Fighter Command. On 8 December 1940 a directive from the Air Staff calledfor Sector Offensive Sweeps. It ordered hit-and-run operations over Belgium andFrance. The operations were to be conducted by three squadrons to harass Germanair defences. On 10 January 1941 Circus attacks were initiated by sending smallbomber formations protected by large numbers of fighters. The escalation ofoffensive operations throughout 1941 was designed to draw up the Luftwaffe asDouglas\' command took an increasingly offensive stance. These operations becameknown as the Circus offensive.[34] Trafford Leigh-Mallory, AOC 11 Group, pennedOperations Instruction No. 7, which he had written on 16 February.Leigh-Mallory outlined six distinct operations for day fighters: Ramrod (bomberescort with primary goal the destruction of the target); Fighter Ramrod (thesame goal where fighters escorted ground-attack fighters); Roadstead (bomberescort and anti-shipping operations); Fighter Roadstead (the same operation asRoadstead but without bombers) along with Rhubarb (poor weather ground attackoperation) and Circus operations (see glossary). Johnson\'sfirst contact with enemy single-engine fighters did not go as planned. Baderundertook a patrol with Dundas as his number two. Johnson followed in hissection as number three with Whaley \"Nip\" Heppell guarding his tailas Red Four. Johnson spotted three Bf 109s a few hundred feet higher andtravelling in the same direction. Johnson, forgetting to calmly report thenumber, type and position of the enemy, shouted, \"Look out Dogsbody!\"(Bader\'s call sign). Such a call was only to be used if the pilot in questionwas in imminent danger of being attacked. The section broke in all directionsand headed to Tangmere singly. The mistake brought an embarrassing rebuke fromBader at the debriefing. Johnsonflew various operations over France including the Rhubarb ground attackmissions which Johnson hated—he considered it a waste of pilots. Severalsuccessful fighter pilots had been lost this way. Flight Lieutenant Eric Lockand Wing Commander Paddy Finucane were killed on Rhubarb operations in August1941 and July 1942 respectively. Squadron leader Robert Stanford Tuck would becaptured carrying out a similar operation in January 1942. During this time,Dundas and other pilots also expressed dissatisfaction with the formationtactics being used in the wing. After a long conversation into the early hours,Bader accepted the suggestions by his senior pilots and agreed to the use ofmore flexible tactics to lessen the chances of being taken by surprise. Thetactical changes involved operating overlapping line abreast formations similarto the German finger-four formation. The tactics were used thereafter by allRAF pilots in the wing. The first use of these tactics by the Tangmere Wing wasused on 6 May 1941. The wing engaged Bf 109Fs from Jagdgeschwader 51 (FighterWing 51), led by Werner Mölders. Noticing the approaching Germans below andbehind them, the Spitfires feigned ignorance. Waiting for the optimum moment toturn the tables, Bader called for them to break, and whip around behind the Bf109s. Unfortunately for the Tangmere Wing, while the tactic had been successfulin avoiding a surprise attack, the break was mistimed. It left some Bf 109sstill behind the Spitfires. In the battle that followed the wing shot down oneBf 109 and damaged another, although Dundas was shot down for the second timein his career—and once again by Mölders, who had remained behind the British.Dundas was able to nurse his crippled fighter back to base and crash-land. Onemonth later, Johnson gained his first air victory. On 26 June Johnsonparticipated in Circus 24. Crossing the coast near Gravelines, Bader warned of24 Bf 109s nearby, southeast, in front of the wing. The Bf 109s saw the Britishand turned to attack the lower No. 610 Squadron from the rear. While watchingthree Bf 109s above him dive to port, Johnson lost sight of his wing commanderat 15,000 feet. Immediately a Bf 109E flew in front of him and turned slightlyto port at a range of 150 yards. After receiving hits, the Bf 109\'s hood wasjettisoned and the pilot baled out. Several No. 145 Squadron pilots witnessedthe victory. He had expended 278 rounds from P7837\'s guns. The Bf 109 was oneof five lost by Jagdgeschwader 2 (Fighter Wing 2) that day. A flurry of actionfollowed. On 1 July 1941 he expended 89 rounds and damaged a Bf 109E. Bader\'ssection was attacked and Johnson out-turned his assailant. Firing, he sawglycol streaming behind it. On 14 July, the Tangmere Wing flew on Circus 48 toSt Omer. Losing sight of the squadron, Johnson and his wingman proceeded inlandat 3,000 feet after spotting three aircraft. Turning in behind them, heidentified them as Bf 109Fs. Johnson dived so as to come up and underneath intothe enemy\'s blind spot. Closing to 15 yards, he gave the trailing Bf 109 atwo-second burst. The tail was blown off and his windshield was covered in oilfrom the Messerschmitt. Johnson saw the other Bf 109s spinning down out ofcontrol. Having also lost his wingman, Johnson disengaged. Climbing andcrossing the coast at Etaples, Johnson bounced a Bf 109E. Giving chase in adive to 2,000 feet and firing at 150 yards, he observed something flying offthe Bf 109\'s starboard wing. Johnson could not see any more owing to the oil-coveredwindscreen and did not make a claim. His second victory was probablyUnteroffizier (corporal) R. Klienike, III./Jagdgeschwader 26 (Third Group,Fighter Wing 26) who was posted missing. On21 July, Johnson shared in the destruction of another Bf 109 with Pilot OfficerHeppell. Johnson\'s wingman disappeared during the battle. Sergeant Mabbet wasmortally wounded but made a wheels-up landing near St Omer. Impressed with hisskilful flying while badly wounded, the Germans buried him with full honours. On23 July, Johnson damaged another Bf 109. During this battle Adolf Galland,Geschwaderkommodore (wing commander) of JG 26 was wounded; his life was savedby a recently installed armour plate behind his head. Johnsontook part in the 9 August 1941 mission in which Bader was lost over France. Onthat day Douglas Bader had been without his usual wingman Sir Alan Smith whowas unable to fly due to having a head cold. During the sortie, Johnsondestroyed a solitary Messerschmitt Bf 109. Johnson flew as wingman to Dundas inBader\'s section. As the wing crossed the coast, around 70 Bf 109s were reportedin the area, the Luftwaffe aircraft outnumbering Bader\'s wing by 3:1. Spottinga group of Bf 109s 1,000 feet below them, Bader led a bounce on a lower group.The formations fell apart and the air battle became a mass of twistingaircraft. It seemed to me the biggest danger was a collision rather than beingshot down, that\'s how close we all were. We got the 109s we were bouncing then(Squadron Leader) Holden came down with his section, so there were a lot ofaeroplanes ... just 50 yards apart. It was awful ... all you could think aboutwas surviving, getting out of that mass of aircraft. Johnson exited the meleeand was then immediately attacked by three Bf 109s. The closest was 100 yardsaway. Maintaining a steep, tight, spiralling turn, he dived into cloud andimmediately headed for Dover. Coming out of the cloud, Johnson saw a lone Bf109. Suspecting it to be one of the three that had chased him, he searched for theother two. Seeing nothing, Johnson attacked and shot it down. It was his fourthvictory. Johnson ended his month\'s tally by adding a probable victory on 21August. But it had been a bad day and month for the wing. The much loathedCircus and Rhubarb raids had cost Fighter Command 108 fighters. The Germanslost just 18. On 4 September 1941 Johnson was promoted to flight lieutenant andawarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). Johnson\'slast certain victories of the year were achieved on 21 September 1941.Escorting Bristol Blenheims to Gosnay, the top cover wings failed to rendezvouswith the bombers. Near Le Touquet at 15:15 and around 20,000 feet, Johnson\'ssection was bounced by 30 Bf 109s. Johnson broke and turned in and behind a Bf109F. Approaching from a quarter astern and slightly below, Johnson firedclosing from 200 to 70 yards. Pilot Officer Smith of Johnson\'s section observedthe pilot bail out. Pursued by several enemy aircraft, Johnson dived to groundlevel. About 10 miles off Le Touquet, other Bf 109s attacked. Allowing theGermans to close within range, Johnson turned into a steep left-hand turn. Ittook him onto the tail of a Bf 109. Johnson fired and broke away at 50 yards.The Bf 109 was hit, stalled and crashed into the sea. Johnson was pursued until10 miles south of Dover. The two victories made Johnson\'s total to sixdestroyed, which now meant he was an official flying ace. In winter 1941,Johnson and 616 Squadron moved to training duties. The odd convoy patrol wasflown but it was an idle period for the squadron which had now concluded its\"Tangmere tour\". Squadronleader to Wing Commander: On31 January 1942, the squadron moved to RAF Kings Cliffe. After an uneventfulfew months, RAF Fighter Command resumed its offensive policy in April 1942 whenthe weather cleared for large-scale operations. Johnnie flew seven sweeps thatmonth. But the situation had now changed. The Spitfire V, which was flown bythe RAF had been a match for the Bf 109F, however, the Germans had introduced anew fighter: the Focke-Wulf Fw 190. It was faster at all altitudes below 25,000feet, possessed a faster roll rate, was more heavily armed and could out-diveand out-climb the Spitfire. Only in the turn could the Spitfire outperform theFw 190. The introduction of this new enemy fighter resulted in heavier casualtyrates among the Spitfire squadrons until a new mark of Spitfire could beproduced. Johnson claimed a damaged Fw 190 on 15 April 1942 but he witnessedthe Fw 190s get the better of the British pilots consistently throughout mostof 1942: Yes, the 190 was causing us real problems at this time. We couldout-turn it, but you couldn\'t turn all day. As the number of 190s increased, sothe depth of our penetrations decreased. They drove us back to the coastreally. On25 May, Johnson experienced an unusual mission. His section engaged a DornierDo 217 carrying British markings, four miles west of his base. Johnson allowedthe three inexperienced pilots to attack it, but they only managed to damagethe bomber. Days later, on 26 June 1942, Johnson was awarded the bar to hisDFC. More welcome news was received late in the month as the first Spitfire Mk.IXs began reaching RAF units. On 10 July 1942, Johnson was promoted to the rankof squadron leader, effective as of 13 July, and given command of 610 Squadron.In rhubarb operations over France, Johnson\'s wing commander, Patrick Jameson,insisted that the line-astern formation be used which caused Johnson toquestion why tactics such as the finger-four had not been universally adopted.Johnson criticised the lack of tactical consistency and when his squadron flewtop cover, he often changed to the finger-four as soon as they reached theFrench coast, hoping his wing leader would not notice. ByAugust 1942, preparations were begun for a major operation, Jubilee, at Dieppe.The Dieppe raid took place on 19 August 1942. Johnson took off at 07:40 inSpitfire VB. EP254, DW-B. Running into around 50 Bf 109s and Fw 190s in fours,pairs and singly. In a climbing attack Johnson shot down one Fw 190 which crashedinto the sea and shared in the destruction of a Bf 109F. While heading back tobase, Johnson attacked an alert Fw 190 which met his attack head on. Thedogfight descended from 8,000 to zero feet. Flying over Dieppe, Johnson divedtowards a destroyer in the hope its fire would drive off the Fw 190, now on histail. The move worked and Johnson landed back at RAF West Malling at 09:20. Forthe remainder of the year, the squadron was moved to RAF Castletown inSeptember 1942 to protect the Royal Navy fleet at Scapa Flow. Johnson tookcommand of No. 127 Wing RCAF based at RAF Kenley after Christmas and theyreceived the new Spitfire IX: the answer to the Fw 190. After gaining aprobable against a Fw 190 in February 1943, Johnnie selected Spitfire EN398after a 50-minute test flight on 22 March 1943. It became his regular mount.Being a wing commander now meant his initials could be painted on the machine.His Spitfires now carried JE-J. He was also allotted the call sign\"Greycap\". Johnson set about changing the wing\'s tactical approach.He quickly forced the wing to abandon the line-astern tactics for thefinger-four formation which offered much more safety in combat; enablingmultiple pilots to participate in scanning the skies for enemy aircraft so asto avoid an attack, and also being better able to spot and position their unitfor a surprise attack upon the enemy. Johnson made another alteration to hisunits operations. He loathed ground-attack missions which highly trainedfighter pilots were forced to participate in. He abandoned ground attackmissions whenever he could.[54] During these weeks, Johnson\'s wing escortedUnited States Army Air Forces (USAAF) bombers to targets in France. On afighter sweep, Ramrod 49, Johnson destroyed an Fw 190 for his eighth victory.Unteroffizier Hans Hiess from 6. Staffel bailed out, but his parachute failedto open. Thespring proved to be a busy one; Johnson claimed three Fw 190s damaged two dayslater. On 11 and 13 May he destroyed an Fw 190 to reach ten individual air victorieswhile sharing in the destruction of another on the later date and a Bf 109 on 1June. A further five victories against Fw 190s were achieved in June. Two wereclaimed on 15 June. On 17 June while leading the wing over Calais Johnsonbounced one of JG 26\'s Gruppen led by Wilhelm-Ferdinand Galland. He shot downUnteroffizier Gunther Freitag, 8./JG 26 who was killed. On 24 June he claimedone destroyed and one damaged on and another victory on the 27th to bring histotal to 15. Johnsonscored more success in July. The USAAF began Blitz Week; a concentrated effortagainst German targets. Escorting American bombers, Johnson destroyed three Bf109s and damaged another, the last being shot down on 30 July; his tally stoodat 18. There was still no standard formation procedure in Fighter Command, andJohnson\'s use of the finger-four made the wing distinct in the air. It earned144 Wing the nickname \"Wolfpack\". The name remained until 144 Wingwas moved to an Advanced Landing Ground (ALG) at Lashenden and was renamed No.127 Wing RCAF, part of the RAF Second Tactical Air Force under the command ofNo. 83 Group RAF. The tactics proved successful in the Canadian wing. Johnsonscored his 19th to 21st victories on 23 and 26 August, whilst claiming yet anotherFw 190 on 4 September 1943. Johnson\'s 19th victory was gained againstOberfeldwebel (First-Sergeant) Erich Borounik 10./JG 26, who was killed. Johnson\'s21st victim, Oberfeldwebel Walter Grunlinger 10./JG 26, was also killed. Johnson\'sportrait is included in a montage of eighteen pilots painted by Olive Snell atRAF Westhampnett in 1943; it is now in the Goodwood collection on the samesite. Normandy to theRhine: Inthe lead up to the Battle of Normandy and the D-Day landings Johnson continuedto score regularly. His 22nd and 23rd victories were achieved on 25 April 1944and Johnson became the highest scoring ace still on operations. These victorieswere followed by another Fw 190 on 5 May (no. 24); III./JG 26 lost FeldwebelHorst Schwentick and Unteroffizier Manfred Talkenberg killed during the airbattle. After the landings in France on 6 June 1944, Johnson added further tohis tally, claiming another five aerial victories that month including two Bf109s on 28 June. The mission in which Johnson recorded his 26th victory on 22June was particularly eventful; four more Fw 190s fell to his wing. Afterbouncing a formation of Bf 109s and Fw 190s, he shot down a Bf 109 for his 29thvictory. Five days later, Johnson destroyed two Fw 190s to reach his 30th and31st air victories. Johnson\'swing was the first to be stationed on French soil following the invasion. Withtheir radius of action now far extended compared to the squadrons still inBritain, the wing scored heavily through the summer. On 21 August 1944, Johnsonwas leading No. 443 Squadron on a patrol over the Seine, near Paris. Johnsonbounced a formation of Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, shooting down two, which wererecorded on the cine camera.[68] Climbing back to his starting point at 8,000ft, Johnson attempted to join a formation of six aircraft, he thought wereSpitfires. The fighters were actually Messerschmitt Bf 109s. Johnson escaped bydoing a series of steep climbs, during which he nearly stalled and blacked out.He eventually evaded the Messerschmitts, which had been trying to flank him oneither side, while two more stuck to his tail. Johnson\'s Spitfire IX was hit byenemy aircraft fire for the only time, taking cannon shells in the rudder andelevators.[69] Johnson had now equalled and surpassed Sailor Malan\'s recordscore of 32, shooting down two Fw 190s for his 32nd and 33rd air victories. HoweverJohnson considered Malan\'s exploits to be better. Johnson points out, whenMalan fought (during 1940–41), he did so outnumbered, and had matched the enemyeven then. Johnson said: Malanhad fought with great distinction when the odds were against him. He matchedhis handful of Spitfires against greatly superior numbers of Luftwaffe fightersand bombers. He had been forced to fight a defensive battle over southernEngland and often at a tactical disadvantage, when the top-cover Messerschmitts[Bf 109s and Bf 110s] were high in the sun. I had always fought on theoffensive, and, after 1941, I had either a squadron, a wing or sometimes twowings behind me. In September 1944 Johnson\'s wing participated in supportactions for Operation Market Garden in the Netherlands. On 27 September 1944,Johnson\'s last victory of the war was over Nijmegen. His flight bounced aformation of nine Bf 109s, one of which Johnson shot down. During this combatSquadron Leader Henry \"Wally\" McLeod, of the Royal Canadian AirForce, and his squadron had joined Johnson. During this action McLeod wentmissing, possibly shot down by Siegfried Freytag of Jagdgeschwader 77 (FighterWing 77). Thewing rarely saw enemy aircraft for the remainder of the year. Only on 1 January1945 did the Germans appear in large numbers, during Operation Bodenplatte tosupport their faltering attack in the Ardennes. Johnson witnessed the Germanattack on his wing\'s airfield at Brussels–Melsbroek. He recalled the Germansseemed inexperienced and their shooting was \"atrocious\". Johnson leda Spitfire patrol to prevent a second wave of German aircraft attacking butengaged no enemy aircraft, since there was no follow-up attack. From lateJanuary and through most of February, Johnson reduced his flying time. InMarch 1945, Johnson patrolled as Operation Plunder and Operation Varsity pushedAllied armies into Germany. There was little sign of the Luftwaffe. Numerousground-attack operations were carried out instead. On 26 March Johnson\'s wingwas relocated to Twente and he was promoted to group captain. Days laterJohnson took command of No. 125 Wing. On 5 April, after returning from patrolin Spitfire Mk XIV MV268, he switched off the engine just as a Bf 109 flewoverhead. Seeing the Spitfire, it turned in for an attack; Johnson took coverunder his fighter while the airfield defences shot down the 109. On 16 April1945 Johnson\'s wing moved to RAF Celle in Germany. Duringthe last week of the war, Johnson\'s squadron flew patrols over Berlin and Kielas German resistance crumbled. During a flight over central Germany looking forjet fighters, Johnson\'s squadron attacked Luftwaffe airfields. On one sortie,his unit strafed and destroyed 11 Bf 109s that were preparing to take off. Onanother sortie, an enemy transport was sighted, but took evasive action andretreated back to German held territory but Johnson\'s pilots shot it down. Onanother occasion, Johnson intercepted a flight of four Fw 190s. The Germanfighters, however, waggled their wings to signal non-hostile intent andJohnson\'s unit escorted them to an RAF airfield. After the German capitulationin May 1945, Johnson relocated with his unit to Copenhagen, Denmark. Here, hisassociation with the Belgian No. 350 Squadron RAF led him to be awarded theCroix de Guerre with Palm and the rank of officer of the Order of Léopold withPalms. Korean War: Duringan exchange posting to the US Air Force, in 1950 he served in the Korean Warflying the Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star, and later flew the North American F-86Sabres with the US Air Force Tactical Air Command. Johnson did not leave anywritten record of his experiences but at the end of his tour received the US AirMedal and Legion of Merit. In 1951, Johnson commanded a wing at RAF Fassberg, astation in the RAF Second Tactical Air Force in West Germany. In 1952, he waspromoted to group captain and commanded RAF Wildenrath in West Germany until1954. From 1954 to 1957 he was deputy director operations (DD(Ops)) at the AirMinistry in London. In 1956 his wartime memoir, Wing Leader was published. On20 October 1957, Johnson became commanding officer of RAF Cottesmore in the UK,commanding a station operating the Victor V bomber. In 1960 he was promoted toair commodore and attended the Imperial Defence College (IDC) course in Londonand in June 1960 was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE)for his work as station commander at Cottesmore. After the course he was postedto the headquarters of No. 3 Group RAF of Bomber Command at RAF Mildenhall. On1 October 1963 he was promoted to air vice marshal and served as air officercommanding (AOC) RAF Middle East based at Aden. In 1964 he published his bookFull Circle, a history of air fighting, co-written with Percy\"Laddie\" Lucas, a former Member of Parliament and Douglas Bader\'sbrother-in-law. In 1965 on retirement from the RAF he was appointed a Companionof the Order of the Bath (CB). THISIS AN AUTHENTIC HAND AUTOGRAPHED 8x10 PHOTOGRAPH. I ONLY SELL AUTHENTIC HANDAUTOGRAPHED MEMORABILIA. I do not sell reprints or facsimile autographs. Whenyou offer on my items you will receive the real deal authentic hand autographeditems. You will receive the same signed photograph that is pictured in thescan. If you have any questions feel free to e-mail me. I combine S&H whenmultiple items are purchased. I ship items internationally the price forinternational S&H varies by country. I currently have other rareautographed historical and sports signed items available. Please take a look atmy other sales of rare military, historical and sports autographed items.

British WWII Dated Royal Air Force Holster- Genuine WW2 RAF $29.95

British WWII RAF and Special Forces Survival Knife with Leather Sheath $79.95

WW2 WWII RAF MK VII Flying Goggles $697.20

WWII RAF Pilots Wings Silver Bullion $20.00

British RAF Blue/Gray Canvas Holster 23/175 Clean WWII WW2 Royal Army. $29.99

WW2 WWII Military RAF British Royal Air Force Cloth Pilot Observer Wing Original $39.99

WWII RAF / RCAF Air Force Air Crew Crash Ditch Survival Raft Knife #158983 $127.17

WWII RAF / RCAF Air Force Air Crew Crash Ditch Survival Raft Knife #158986 $127.17

|