|

On eBay Now...

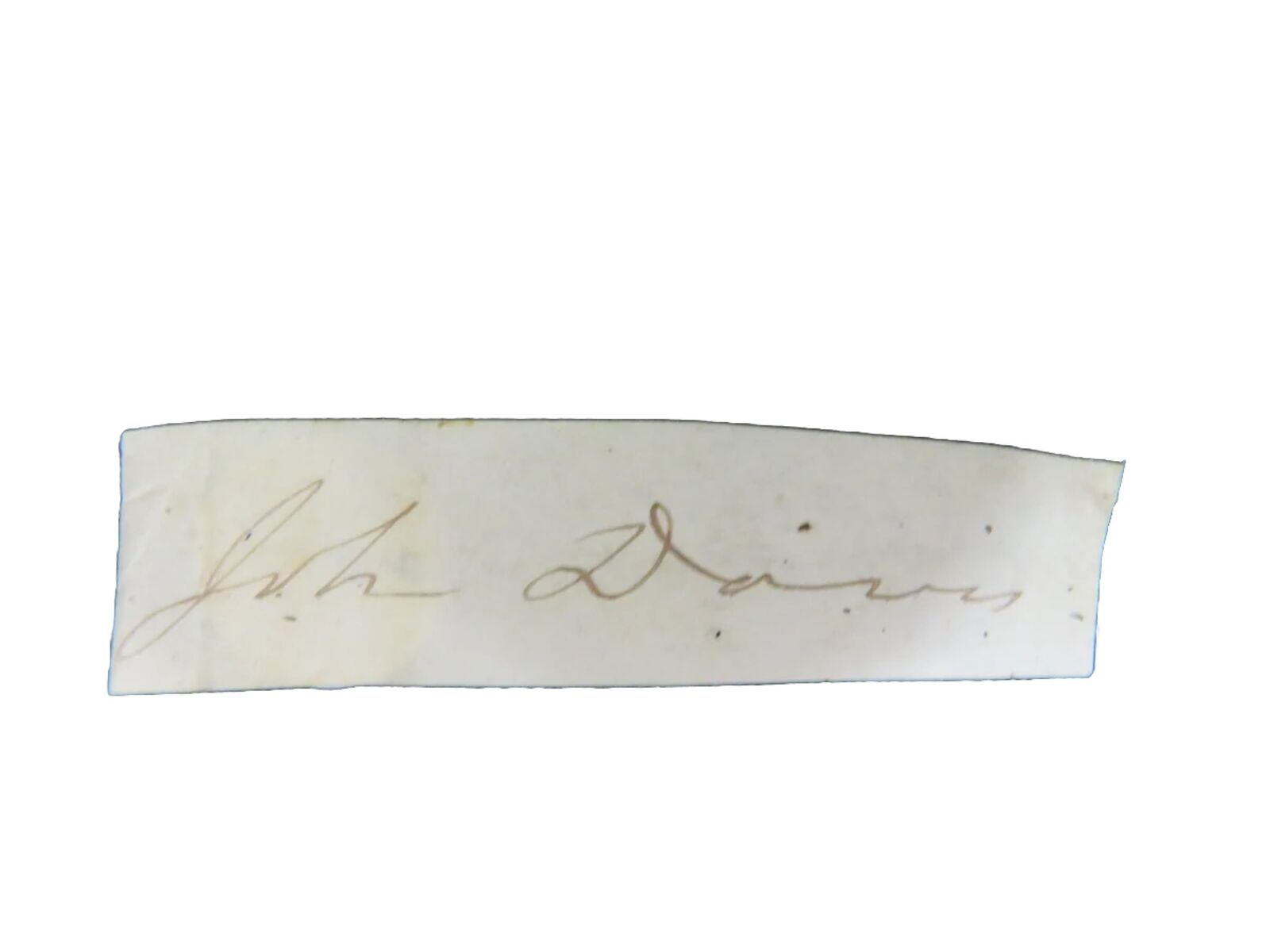

RARE “Massachusetts Governor\" John Davis Cut Siganture For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

RARE “Massachusetts Governor\" John Davis Cut Siganture:

$49.99

Up for sale "Massachusetts Governor" John Davis Clipped Siganture.

– April 19, 1854) was an American lawyer, businessman and politician from Massachusetts. He spent 25 years in public service, serving in both houses of the United States Congress and for three non-consecutive years as Governor of Massachusetts. Because of his reputation for personal integrity he was known as "Honest John" Davis. Born in Northborough, Massachusetts, Davis attended Yale College before studying law in Worcester, Massachusetts, where he established a successful law practice. He spent 10 years (1824–34) in the United States House of Representatives as a National Republican (later Whig), where he supported protectionist tariff legislation. He won election as Governor of Massachusetts in a three-way race in 1833 that was decided by the state legislature. After two terms he was elected to the United States Senate, where he served most of one term, resigning early in 1841 after he was once again elected governor. His second term as governor was undistinguished, but he split with fellow Whig Daniel Webster over a variety of issues, and lost the 1843 election to Democrat Marcus Morton. He was reelected to the Senate in 1845, where he served until 1851. He opposed the Mexican–American War, and worked to prevent the extension of slavery to the territories, although he did not take a hard line on the matter, voting for most of the provisions of the Compromise of 1850. He retired from public service in 1853, and died the next year. John Davis was born Deacon Isaac Davis and Anna (Brigham) Davis. He attended local schools and then Leicester Academy before attending Yale College. He graduated in 1812, and then studied Blake, gaining admission to the bar three years later. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1821. Davis first practiced law in Spencer, Massachusetts, but soon returned to Worcester, where he eventually took over Blake's practice. He was briefly in partnership with Levi Lincoln, Jr. before the latter was appointed to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court in 1824. Davis also entered politics in 1824, winning election to the United States Congress. He represented Massachusetts from 1825 to 1833 in the House of Congresses. He supported John Quincy Adams in his successful offer for the presidency, and favored conservative fiscal policies. In keeping with the state's (and Worcester's) increasingly industrial character, he favored protectionist tariff legislation; his speeches in support of the Tariff of 1828 were widely reprinted. He opposed the policies of President Andrew Jackson, and was politically aligned with Henry Clay, although he was against Clay's proposed compromise tariff of 1833. In 1833 Davis was encouraged by National Republican Party leaders to run for Governor of Massachusetts, against former President John Quincy Adams, who was running on Morton. His political support came from textile interests and a faction of the National Republicans (later Whigs) led by Abbott Lawrence, as well as outgoing Governor Levi Lincoln, Jr. In the election Davis gained a plurality of votes, but not the majority that was then required. As a result, the state legislature decided the election, choosing Davis when Adams withdrew, preferring him over Morton. The Whig-controlled legislature did nothing to reward the Anti-Masons for Adams's move, breaking up any chance that the two parties would form a working relationship. Davis was reelected in 1834, aided by a general dislike in Massachusetts for President Jackson's attacks on the Second Bank of the United States. During these two terms, Davis made no particular initiatives of his own, continuing Lincoln's business-friendly fiscal and economic policies. The state continued to grow economically, expanding its transportation infrastructure and industry. Senator Nathaniel Silsbee, whose term ended in 1835, decided not to run for reelection.[8] Davis was approached by Whig leader Daniel Webster about running for the seat in December 1834, as part of a offer to oppose Adams, who had announced his interest in the seat. The idea was that Davis, a strong candidate, would be positioned against Adams (a long-standing rival of Webster who was again running as an Anti-Mason) in the vote, which would be made by the state legislature, while Edward Everett would have the opportunity to run for governor when Davis vacated that seat. The state house and senate deadlocked on the two choices until a speech by Adams in Congress arguing in favor of Jackson's foreign policies alarmed enough senators to change their votes in favor of Davis. The deadlock was not resolved until February 1835; Davis, who had been reelected governor, resigned that post to assume the Senate seat. Everett went on to win the governor's seat in the next election. (Adams's son Charles Francis believed that Webster and Everett conspired to achieve this end, but there is no evidentiary support for the idea.) Webster, in exchange for his advocacy on behalf of Davis, expected Davis's faction in the Whig Party to support him in a future offer for the presidency. Davis's term in the Senate was unexceptional, except for the notably hard line he took on the question of the nation's northeastern boundary. This dispute with the United Kingdom concerned the boundary between Maine and the British (now Canadian) province of New Brunswick, and had only been partially resolved after the 1794 Jay Treaty. In the 1830s both sides pushed development into the disputed area, leading to petty conflicts (and by 1839 the possibility of war). Massachusetts, which Maine had been a part of prior to 1820, maintained a property interest in some of the disputed land; Davis took a hard line on the matter, insisting that the United States should not surrender any of the territory it claimed. In 1836 Davis sat on a special committee formed to consider legislative responses to a flood of allegedly inflammatory abolitionist materials being sent into southern slave states from northern anti-slavery organizations. Davis, the only northerner on the committee, opposed any sort of legislation, and the committee was unable to reach a consensus. When John C. Calhoun introduced legislation criminalizing the mailing of such materials, Davis spoke out against it, pointing out that it would effectively act as an unconstitutional gag on people seeking to speak out against slavery. The bill was rendered moot by administrative actions in the United States Post Office. While serving in the Senate, Davis appeared before the United States Supreme Court in 1837, representing the defendants in Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge. The plaintiffs were proprietors of the Charles River Bridge, a toll bridge constructed between Boston and Charlestown in 1786, and the defendants were proprietors of a competing bridge to which the state had issued a charter in 1828. The plaintiffs argued that the defendant's charter infringed on their charter, in which they claimed the state granted them an exclusive right to control the crossing. Davis and that the rights granted to the Charles River proprietors had to be interpreted narrowly, and that the state had not granted them an exclusive right. The court found for the defendants, with Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's decision echoing the defendant's reasoning. The Charles River Bridge charter would be acquired by the state in 1841, during Davis's next term as governor. During the early years of his political career Davis was on good terms with Daniel Webster, who was highly influential in party politics both at the state and national levels, and to whom he looked up. However, in the late 1830s Davis and other Massachusetts Whigs (notably Abbott Lawrence) came to believe that Webster lacked broad-based national support to successfully contend with Henry Clay and William Henry Harrison after his weak showing in the 1836 Whig convention. This introduced a rift between Webster and Davis that deepened in 1838 when the two split on western land policies. The split between Davis and Webster became permanent after Webster harshly criticized Lawrence in an 1842 speech celebrating his successful negotiation of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with Great Britain, which resolved (among other matters) the northeast boundary. Not long after Marcus Morton won the 1839 gubernatorial election, Whig leadership prevailed on Davis to run again for governor. In the 1840 election Davis rode the coattails victory into office. Harrison's death in April 1841 reenergized the Democrats, who attacked Davis in that year's election. They charged that protectionist tariffs he supported taxed the poor, and that his opposition to western land policies was hypocritical because he also speculated in those lands. Davis won a narrow majority over Morton and was reelected in 1841. This period in office, like his first term as governor, also did not contain any new programs or initiatives, but was overshadowed by the ongoing negotiations between Daniel Webster (now Secretary of the boundary issue. Davis and Webster had contentious disagreements over the negotiations, although Webster was finally able to convince Davis to accept the final agreement. The matter deepened the division between the two men, who stopped speaking to each other. In 1842 risen to sufficient prominence in the state that neither Morton nor Davis was able to secure a majority. The state senate, which had a Democratic majority, elected Morton. Davis's showing in the election was undoubtedly harmed by his ongoing feud with Webster, who refused to campaign on his behalf. Davis was considered as a potential vice presidential nominee in the 1844 Whig Party convention. He was nominated by the state Whig convention over Webster's opposition, but Webster worked to ensure he was not chosen at the national convention. Webster forces successfully got Webster elected to the Senate in early 1845, despite opposition from the Lawrence-Davis faction. Davis was himself elected to the Senate again later in 1845 to fill the vacancy caused by the death of Isaac C. Bates, and was elected to a full term in 1847. He opposed the annexation of Texas on the grounds that it would expand slaveholding territory, but was not willing to split the party over the issue of slavery. Davis was one of only two senators who voted against the Mexican–American War. Davis was opposed to slavery and its extension into the territories, but he voted for most of the provisions of the Compromise of 1850, including the bill on Texas borders, shocking some anti-compromise Whigs. He regularly voted in favor of the Wilmot Proviso, a measure to ban slavery from territories won in the Mexican war which was frequently attached to legislation in the late 1840s but was never adopted. In one notable debate, Davis used procedural measures to delay vote on an amendment to remove it from a military appropriations bill, hoping to force a vote without time to conference on differences between the House and Senate versions before Congress adjourned. However, due to a difference in the clocks in the respective chambers, the House adjourned before he finished speaking, scuttling the bill. Salmon P. Chase wrote of the episode, "Ten political lives of ten John Davises, spent in the best direction, could not compensate for this half-hour's mischief", and Polk noted that if the loss of the bill delayed the end of the Mexican war, Davis would "deserve the execrations of the country." Scholarship is divided on whether Davis's claimed strategy would really have worked. Davis's weak stance on slavery began to cause a decrease in his popularity as abolitionist sentiment in the state gained ground during the 1840s. He also refused to support Webster in his 1852 presidential offer, campaigning on behalf of Winfield Scott. He declined renomination for election in 1852, and retired from public life. In his later years Davis was associated with the American Antiquarian Society, where he served as president for many years. He died in Worcester on April 19, 1854, and was interred in the Worcester Rural Cemetery. He was known as "Honest John" Davis, because of an impeccable reputation for personal integrity.

Charles River Motel Boston Massachusetts Vintage Postcard (Extremely Rare) $31.47

RARE "Massachusetts Congressman" Fisher Ames Clipped Signature $299.99

RARE “Massachusetts Politician" Alexander De Witt Hand Written Letter $349.99

VINTAGE RARE | Massachusetts Landmark Collectors Plate $30.00

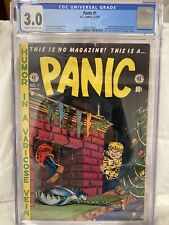

Panic #1 (E.C. Comics, 1954) Rare Controversial, Banned in Massachusetts CGC 3.0 $550.00

Rare Massachusetts DEPT. OF PUBLIC WORKS Badge Motor Vehicle Registration $29.99

Rare Post Card Magnolia Fire Station, GLOUCESTER MASS. Cape RPPC $59.88

RARE “Massachusetts Governor" William B. Washburn Cut Signature $69.99

|