|

On eBay Now...

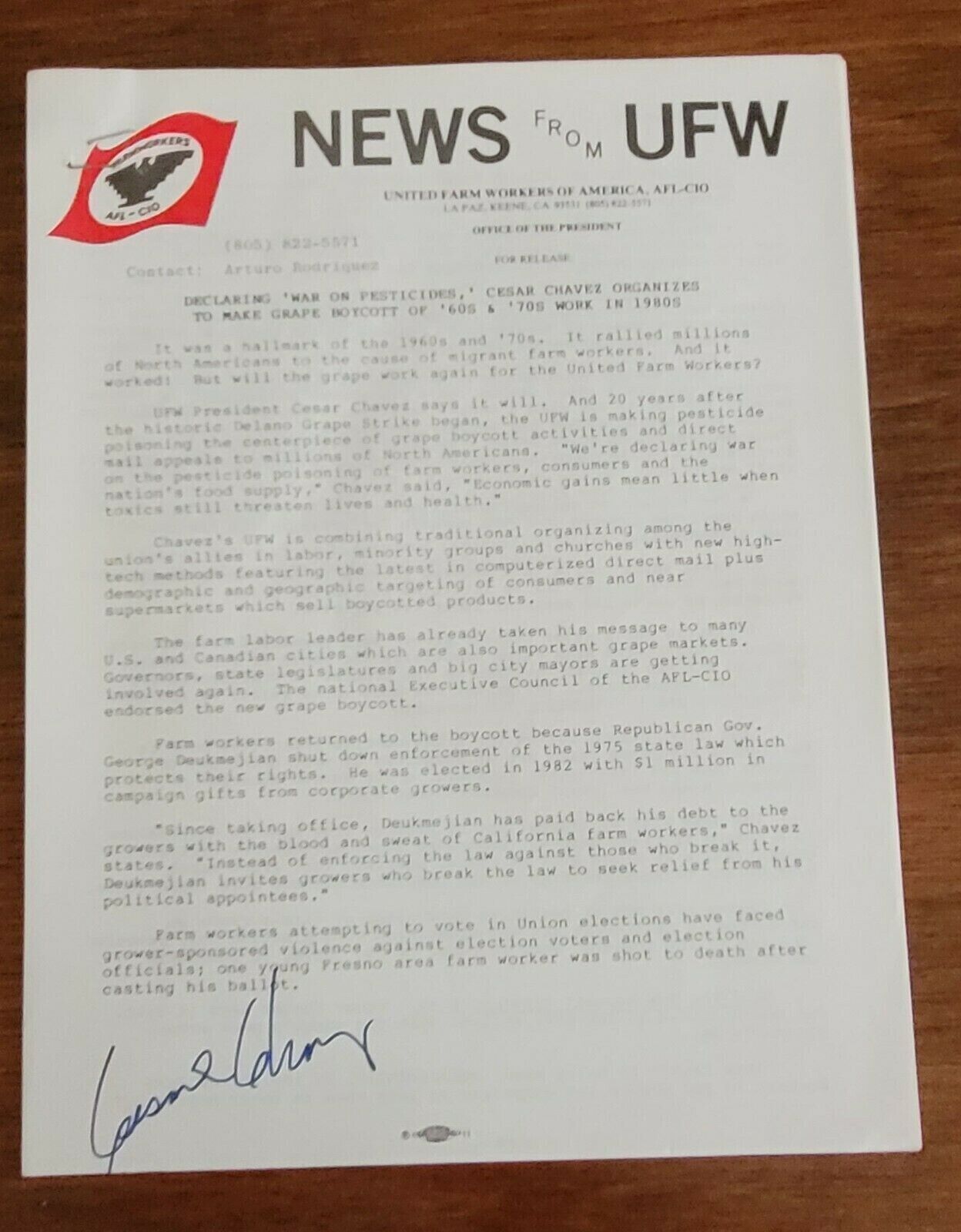

RARE AUTOGRAPH MEXICAN AMERICAN LABOR LEADER AFL-CIO CESAR CHAVEZ DOCUMENT UFW For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

RARE AUTOGRAPH MEXICAN AMERICAN LABOR LEADER AFL-CIO CESAR CHAVEZ DOCUMENT UFW:

$1725.22

A VINTAGE NEWS FROM UFW SIGNED DOCUMENT WITH MANY ARTIC LES (SOME SHOWN IN IMAGES) HAND SIGNED BY CIVIL RIGHTS AND LABOR RIGHTS LEADER CESAR CHAVEZ

1ST PAGE SAYS

DECLARING \'WAR ON PESTICIDES\' CESAR CHAVEZ ORGANIZES TO MAKE GRAPE BOYCOTT OF \'60S & \'70S WORK IN 1980S

Cesar Chavez Timeline

Time EventMarch 31, 1927 Cesar Estrada Chavez is born in San Luis, Arizona.1937 Chavez\'s parents lose their farm and begin to work as migrant laborers.1938 Chavez\'s family moves to California, working as farm laborers.1942 After graduating from 8th grade, Chavez becomes a full-time farm worker to help support his family (his father had recently been hurt in a car accident).1944 Chavez challenges segregation (white vs. Mexican) and refuses to sit in the Mexican section of a theater; he is held in custody for an hour.1944-1946 Chavez fought in World War 2, in the US Navy.1948 Chavez and Helen Fabela are married.1952 Chavez joins the Community Service Organization (CSO).1962 Chavez forms the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA).1964 Chavez starts El Malcriado: The Voice of the Farm Worker, the official newspaper of the NFWA.1965 NFWA members go on strike against grape growers and start a local grape boycott.1966 Senator Robert Kennedy supports the NFWA grape boycott.1966 Chavez leads a 250-mile march from Delano to Sacramento, California, to let the public and law-makers know about the mistreatment of farm workers.Feb.-March 1968 Chavez starts his first hunger strike; it lasts for 25 days in February and March (it was done to stop violence against strikers).1968 The nationwide boycott of California grapes begins.1969 Pesticide use is regulated.Dec. 14, 1970 Chavez is jailed for defying a court order againt boycotting.1974 The name of the NFWA changes to United Farm Workers (UFW).1975 The California Labor Relations Act was passed; it was the first law that protected the rights of organizations of farm laborers .1975 Chavez leads a 1,000 mile march through the Central Valley of California, in order to call attention to the union elections.1975 The use of the short-handled hoe (el cortito) is banned by the Supreme Court.1978 Chavez announces that all general lettuce and grape boycotts are ended.1984 Chavez announces a new grape boycott, due the excessive use of pesticides.1987 The UFW produces a film call The Wrath of Grapes, about the dangerous use of pesticides on food.1992 Chavez leads a 1,000-person march calling for improved working conditions in farms.April 23, 1993 Cesar Estrada Chavez dies during a fast.1994 Chavez is awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.2003 The US Post Office issues a Cesar Chavez stamp (first class, 37¢).

Cesar Estrada Chavez, Senator Robert F. Kennedy noted, was \"one of the heroic figures of our time.\"A true American hero, Cesar was a civil rights, Latino, farm worker, and labor leader; a religious and spiritualfigure; a community servant and social entrepreneur; a crusader for nonviolent social change; and anenvironmentalist and consumer advocate.A second-generation American, Cesar was born on March 31, 1927, near his family\'s farm in Yuma, Arizona.At age 10, his family became migrant farm workers after losing their farm in the Great Depression.Throughout his youth and into his adulthood, Cesar migrated across the Southwest laboring in the fields andvineyards, where he was exposed to the hardships and injustices of farm worker life.Cesar attended more than 30 elementary and middle schools. After achieving only an eighth-grade education,he left school to work in the fields fulltime to support his family. Although his formal education ended then,he possessed an insatiable intellectual curiosity, and was self-taught in many fields and well read throughouthis life.Cesar joined the U.S. Navy in 1946 and served in the Western Pacific in the aftermath of World War II. Hereturned from service to marry Helen Fabela, whom he had met working in the vineyards of centralCalifornia. The Chavez family settled in the East San Jose barrio of Sal Si Puedes (“Get Out If You Can”),and would eventually have eight children and thirty-one grandchildren.Cesar\'s life as a community organizer began in 1952 when he joined the Community Service Organization(CSO), a prominent Latino civil rights group. While with the CSO, Cesar coordinated voter registration drivesand conducted campaigns against racial and economic discrimination primarily in urban areas. In the late1950s and early 1960s, Cesar served as CSO\'s national director.Cesar\'s dream, however, was to create an organization to protect and serve farm workers, whose poverty anddisenfranchisement he had shared. In 1962, Cesar resigned from the CSO, leaving the security of a regularpaycheck to found the National Farm Workers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers ofAmerica.For more than three decades, Cesar led the first successful farm workers union in American history, achievingdignity, respect, fair wages, medical coverage, pension benefits, and humane living conditions, as well ascountless other rights and protections for hundreds of thousands of farm workers. Against previouslyinsurmountable odds, he led successful strikes and boycotts that resulted in the first industry-wide laborcontracts in the history of American agriculture. His union\'s efforts brought about the passage of thegroundbreaking 1975 California Agricultural Labor Relations Act to protect farm workers. Today, it remainsthe only law in the nation that protects the farm workers\' right to unionize.The significance and impact of Cesar\'s life transcends any one cause or struggle. He was a unique and humbleleader, in addition to being a great humanitarian and communicator who influenced and inspired millions ofAmericans to seek social justice and civil rights for the poor and disenfranchised in our society. Cesar forgeda diverse and extraordinary national coalition of students, middle-class consumers, trade unionists, religiousgroups, and minorities.A strong believer in the principles of nonviolence practiced by Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King,Jr., Cesar effectively employed peaceful tactics such as fasts, boycotts, strikes, and pilgrimages. In 1968, hefasted for 25 days to affirm his personal commitment and that of the farm labor movement to nonviolence.He fasted again for 25 days in 1972, and in 1988, at the age of 61, he endured a 36-day \"Fast for Life\" tohighlight the harmful impact of pesticides on farm workers and their children.Cesar passed away in his sleep on April 23, 1993, in San Luis, Arizona, only miles from his birthplace of 66years earlier. More than 50,000 people attended his funeral services in the small town of Delano, California,the same community in which he had planted his seed for social justice only decades before.Cesar\'s life cannot be measured in material terms. He never earned more than $6,000 a year. He never owneda house. When Cesar passed, he had no savings to leave to his family.His motto in life – Si se puede (“It can be done”) – embodies the uncommon and invaluable legacy he left forthe world\'s benefit. Since his death, dozens of communities across the nation have renamed schools, parks,streets, libraries, other public facilities, awards and scholarships in his honor, as well as enacting holidays onhis birthday, March 31. In 1994, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, thehighest civilian honor in America.Cesar Chavez – a common man with an uncommon vision for humankind – stood for equality, justice, anddignity for all Americans. His ecumenical principles remain relevant and inspiring today for all people.In 1993, his family and friends established the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation to educate people about the lifeand work of this great American civil rights leader, and to engage all, particularly youth, to carry on his valuesand timeless vision for a better world.Cesar Chavez (born César Estrada Chávez, locally: [ˈsesaɾ esˈtɾaða ˈtʃaβes]; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights activist who, with Dolores Huerta, co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (later the United Farm Workers union, UFW) in 1962.[1] Originally a Mexican American farm worker, Chavez became the best known Latino American civil rights activist, and was strongly promoted by the American labor movement, which was eager to enroll Hispanic members. His public-relations approach to unionism and aggressive but nonviolent tactics made the farm workers\' struggle a moral cause with nationwide support. By the late 1970s, his tactics had forced growers to recognize the UFW as the bargaining agent for 50,000 field workers in California and Florida. However, by the mid-1980s membership in the UFW had dwindled to around 15,000.[2]

During his lifetime, Colegio Cesar Chavez was one of the few institutions named in his honor, but after his death he became a major historical icon for the Latino community, with many schools, streets, and parks being named after him. He has since become an icon for organized labor and leftist politics, symbolizing support for workers and for Hispanic empowerment based on grass roots organizing. He is also famous for popularizing the slogan \"Sí, se puede\" (Spanish for \"Yes, one can\" or, roughly, \"Yes, it can be done\"), which was adopted as the 2008 campaign slogan of Barack Obama. His supporters say his work led to numerous improvements for union laborers. Although the UFW faltered a few years after Chavez died in 1993, he became an iconic \"folk saint\" in the pantheon of Mexican Americans.[3] His birthday, March 31, has become Cesar Chavez Day, a state holiday in California, Colorado, and Texas.

Contents [hide]1 Early life and education2 Activism, 1952–19762.1 Workers\' rights2.2 Immigration2.3 Legislative campaigns3 Setbacks and a change of direction, 1976–19884 Personal life4.1 Death5 Legacy5.1 Awards and honors5.2 Places and things named after Cesar Chavez5.3 Monuments5.4 Cesar Chavez Day5.5 Other commemorations5.6 In popular culture6 Timeline7 See also8 References9 Further reading10 External linksEarly life and educationChavez was born on March 31, 1927, in Yuma, Arizona, in a Mexican-American family of six children.[4] He was the son of Juana Estrada and Librado Chávez. He had two brothers, Richard (1929–2011) and Librado, and two sisters, Rita and Vicki.[5] He was named after his grandfather, Cesario.[6] Chavez grew up in a small adobe home, the same home in which he was born. His family owned a grocery store and a ranch, but their land was lost during the Great Depression. The family\'s home was taken away after his father had agreed to clear eighty acres of land in exchange for the deed to the house, an agreement which was subsequently broken. Later, when Chavez\'s father attempted to purchase the house, he could not pay the interest on the loan and the house was sold back to its original owner.[6] His family then moved to California to become migrant farm workers.

The Chavez family faced many hardships in California. The family would pick peas and lettuce in the winter, cherries and beans in the spring, corn and grapes in the summer, and cotton in the fall.[4] When Chavez was a teenager, he and his older sister Rita would help other farm workers and neighbors by driving those unable to drive to the hospital to see a doctor.[7]

In 1942, Chavez quit school in the seventh grade.[8] It would be his final year of formal schooling, because he did not want his mother to have to work in the fields. Chavez dropped out to become a full-time migrant farm worker.[6] In 1946 he joined the United States Navy and served for two years.[6] Chavez had hoped that he would learn skills in the Navy that would help him later when he returned to civilian life.[9] Later, Chavez described his experience in the military as \"the two worst years of my life\".[10]

Activism, 1952–1976Chavez worked in the fields until 1952, when he became an organizer for the Community Service Organization (CSO), a Latino civil rights group. Father Donald McDonnell who served in Santa Clara County introduced Fred Ross, a community organizer, to Cesar Chavez.[11] Chavez urged Mexican Americans to register and vote, and he traveled throughout California and made speeches in support of workers\' rights. He later became CSO\'s national director in 1958.[12]

Workers\' rightsIn 1962, Chavez left the CSO and co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with Dolores Huerta. It was later called the United Farm Workers (UFW).Chavez speaking at a 1974 United Farm Workers rally in Delano, California.When Filipino American farm workers initiated the Delano grape strike on September 8, 1965, to protest for higher wages, Chavez eagerly supported them. Six months later, Chavez and the NFWA led a strike of California grape pickers on the historic farmworkers march from Delano to the California state capitol in Sacramento for similar goals. The UFW encouraged all Americans to boycott table grapes as a show of support. The strike lasted five years and attracted national attention. In March 1966, the U.S. Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare\'s Subcommittee on Migratory Labor held hearings in California on the strike. During the hearings, subcommittee member Robert F. Kennedy expressed his support for the striking workers.[13]

These activities led to similar movements in Southern Texas in 1966, where the UFW supported fruit workers in Starr County, Texas, and led a march to Austin, in support of UFW farm workers\' rights. In the Midwest, Chavez\'s movement inspired the founding of two midwestern independent unions: Obreros Unidos in Wisconsin in 1966, and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) in Ohio in 1967. Former UFW organizers would also found the Texas Farm Workers Union in 1975.This historic building is the Santa Rita Center (also known as Santa Rita Hall). It is where Cesar Chavez began his 24-day hunger strike on May 11, 1972. Coretta King met with Chavez in the hall during his fast. The structure was listed in the Phoenix Historic Property Register on October 2007.In the early 1970s, the UFW organized strikes and boycotts—including the Salad Bowl strike, the largest farm worker strike in U.S. history—to protest for, and later win, higher wages for those farm workers who were working for grape and lettuce growers. He again fasted to draw public attention. UFW organizers believed that a reduction in produce sales by 15% was sufficient to wipe out the profit margin of the boycotted product.

Chavez undertook a number of \"spiritual fasts\", regarding the act as “a personal spiritual transformation”.[14] In 1968, he fasted for 25 days, promoting the principle of nonviolence.[15] In 1970, Chavez began a fast of \"thanksgiving and hope\" to prepare for pre-arranged civil disobedience by farm workers.[16] Also in 1972, he fasted in response to Arizona’s passage of legislation that prohibited boycotts and strikes by farm workers during the harvest seasons.[16] These fasts were influenced by the Catholic tradition of penance and by Mohandas Gandhi’s fasts and emphasis of nonviolence.[15]

ImmigrationThe UFW during Chavez\'s tenure was committed to restricting immigration. Chavez and Dolores Huerta, cofounder and president of the UFW, fought the Bracero Program that existed from 1942 to 1964. Their opposition stemmed from their belief that the program undermined U.S. workers and exploited the migrant workers. Since the Bracero Program ensured a constant supply of cheap immigrant labor for growers, immigrants could not protest any infringement of their rights, lest they be fired and replaced. Their efforts contributed to Congress ending the Bracero Program in 1964. In 1973, the UFW was one of the first labor unions to oppose proposed employer sanctions that would have prohibited hiring illegal aliens. Later during the 1980s, while Chavez was still working alongside Huerta, he was key in getting the amnesty provisions into the 1986 federal immigration act.[17]

On a few occasions, concerns that illegal alien labor would undermine UFW strike campaigns led to a number of controversial events, which the UFW describes as anti-strikebreaking events, but which have also been interpreted as being anti-immigrant. In 1969, Chavez and members of the UFW marched through the Imperial and Coachella Valleys to the border of Mexico to protest growers\' use of illegal aliens as strikebreakers. Joining him on the march were Reverend Ralph Abernathy and U.S. Senator Walter Mondale.[18] In its early years, the UFW and Chavez went so far as to report illegal aliens who served as strikebreaking replacement workers (as well as those who refused to unionize) to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[19][20][21][22][23]

In 1973, the United Farm Workers set up a \"wet line\" along the United States-Mexico border to prevent Mexican immigrants from entering the United States illegally and potentially undermining the UFW\'s unionization efforts.[24] During one such event, in which Chavez was not involved, some UFW members, under the guidance of Chavez\'s cousin Manuel, physically attacked the strikebreakers after peaceful attempts to persuade them not to cross the border failed.[25][26][27]

Legislative campaignsChavez had long preferred grassroots action to legislative work, but in 1974, propelled by the recent election of the pro-union Jerry Brown as governor of California, as well as a costly battle with the Teamsters union over the organizing of farmworkers, Chavez decided to try to work toward legal victories.[28] Once in office Brown\'s support for the UFW cooled.[28] The UFW decided to organize a 110-mile (180 km) march by a small group of UFW leaders from San Francisco to the E & J Gallo Winery in Modesto. Just a few hundred marchers left San Francisco on February 22, 1975. By the time they reached Modesto on March 1, however, more than 15,000 people had joined the march en route.[28] The success of the Modesto march garnered significant media attention, and helped convince Brown and others that the UFW still had significant popular support.[28]

On June 4, 1975, Governor Brown signed into law the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act (ALRA), which established collective bargaining for farmworkers. The act set up the California Agricultural Labor Relations Board (ALRB) to oversee the process.

In mid-1976, the ALRB ran out of its budgeted money for the year, as a result of a massive amount of work in setting up farmworker elections. The California legislature refused to allocate more money, so the ALRB closed shop for the year.[29] In response, Chavez gathered signatures in order to place Proposition 14 on the ballot, which would guarantee the right of union organizers to visit and recruit farmworkers, even if it meant trespassing on private property controlled by farm owners. The proposition went before California voters in November 1976, but was defeated by a 2–1 margin.[29]

Setbacks and a change of direction, 1976–1988As a result of the failure of Proposition 14, Chavez decided that the UFW suffered from disloyalty, poor motivation and lack of communication.[29] He felt that the union needed to turn into a \"movement\".[30] He took inspiration from the Synanon community of California (which he had visited previously), which had begun as a drug rehabilitation center before turning into a New Age religious organization.[31] Synanon had pioneered what they referred to as \"the Game\", in which each member would be singled out in turn to receive harsh, profanity-laced criticism from the rest of the community.[31] Chavez instituted \"the Game\" at UFW, having volunteers, including senior members of the organization, receive verbal abuse from their peers.[31] He also fired many members, whom he accused of disloyalty; in some cases he accused volunteers of being spies for either the Republican Party or the Communists.[30]

In 1977, Chavez attempted to reach out to Filipino-American farmworkers in a way that ended up backfiring. Acting on the advice of former UFW leader Andy Imutan, Chavez met with then-President of the Philippines Ferdinand Marcos in Manila and endorsed the regime, which was seen by human rights advocates and religious leaders as a vicious dictatorship. This caused a further rift within the UFW, which led to Philip Vera Cruz\'s resignation from the organization.[32][33][34][35]

During this time, Chavez also clashed with other UFW members about policy issues, including the possible creation of local unions for the UFW, which was typical for national unions but which Chavez was firmly against, on the grounds that it detracted from his vision for the UFW as a movement.[29]

By the end of the 1970s, only one member of the UFW\'s original board of directors remained in place.[29]

In the 1980s, with the UFW declining, Chavez got into real-estate development; some of the development projects he was involved with used non-union construction workers, which The New Yorker later termed an \"embarrassment\".[30]

In 1988, Chavez attempted another grape boycott, to protest the exposure of farmworkers to pesticides. Bumper stickers reading \"NO GRAPES\" and \"UVAS NO\" (the translation in Spanish) were widespread.[36] However, the boycott failed. As a result, Chavez undertook what was to be his last fast. He fasted for 35 days before being convinced by others to start eating again. He lost 30 pounds during the fast, and it caused health problems that may have contributed to his death.[30]

Personal lifeWhen Chavez returned home from his service in the military in 1948, he married his high school sweetheart, Helen Fabela. The couple moved to San Jose, California, where they had eight children.[6]

Chavez was a vegan, both because he believed in animal rights and also for his health.[37][38]

Death

The grave of César Chávez is located in the garden of the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument in Keene, California.Chavez died on April 23, 1993, of unspecified natural causes in San Luis, Arizona, in the home of former farm worker and longtime friend Dofla Maria Hau.[6] Chavez was in Arizona helping UFW attorneys defend the union against a lawsuit. Shortly after his death, his widow, Helen Chavez, donated his black nylon union jacket to the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian.[39]

Chavez is buried at the National Chavez Center, on the headquarters campus of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW), at 29700 Woodford-Tehachapi Road in the Keene community of unincorporated Kern County, California.[40][41]

He received belated full military honors from the US Navy at his graveside on April 23, 2015, the 22nd anniversary of his death.[42]

Legacy

Colegio Cesar Chavez advertisement in the 1980 Mount Angel Oktoberfest issue of the Silverton Appeal TribuneThere is a portrait of Chavez in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.[43]

In 2003, the United States Postal Service honored Chavez with a postage stamp.[44]

The American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) nominated him three times for the Nobel Peace Prize.[45]

One of Chavez\'s grandchildren is the professional golfer Sam Chavez.

Awards and honorsIn 1973, Chavez received the Jefferson Award for Greatest Public Service Benefiting the Disadvantaged.[46]

In 1992, Chavez was awarded the Catholic Church\'s Pacem in Terris Award, named after a 1963 encyclical by Pope John XXIII calling upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations.

On September 8, 1994, Chavez was presented posthumously with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton. The award was received by his widow, Helen Chavez.

On December 6, 2006, California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Chavez into the California Hall of Fame.[47]

Places and things named after Cesar Chavez

Chavez visiting Colegio Cesar Chavez.Main article: List of places named after Cesar ChavezAcross the United States, and especially in California, there have been many parks, streets, schools, libraries, university buildings and other establishments named after Chavez. In addition, the census-designated place of Cesar Chavez, Texas is named after him.

Colegio Cesar Chavez, named after Chavez while he was still alive, was a four-year \"college without walls\" in Mount Angel, Oregon, intended for the education of Mexican-Americans, that ran from 1973 to 1983.[48]

On May 18, 2011, Navy Secretary Ray Mabus announced that the Navy would be naming the last of 14 Lewis and Clark-class cargo ships after Cesar Chavez.[49] The USNS Cesar Chavez was launched on May 5, 2012.[50]

Monuments

The National Chavez Center, Keene, California.In 2004, the National Chavez Center was opened on the UFW national headquarters campus in Keene by the César E. Chávez Foundation. It currently consists of a visitor center, memorial garden and his grave site. When it is fully completed, the 187-acre (0.76 km2) site will include a museum and conference center to explore and share Chavez\'s work.[40]

On September 14, 2011, the U.S. Department of the Interior added the 187 acres (76 ha) Nuestra Senora Reina de La Paz ranch to the National Register of Historic Places.[51]

On October 8, 2012, President Barack Obama designated the Cesar E. Chavez National Monument within the National Park system.[52]

California State University San Marcos\'s Chavez Plaza includes a statue to Chavez. In 2007, The University of Texas at Austin unveiled its own Cesar Chavez statue[53] on campus.

The Consolidated Natural Resources Act of 2008 authorized the National Park Service to conduct a special resource study of sites that are significant to the life of Cesar Chavez and the farm labor movement in the western United States. The study evaluated the significance and suitability of sites significant to Cesar Chavez and the farm labor movement, and the feasibility and appropriateness of a National Park Service role in the management of any of these sites.[54]

Cesar Chavez DayMain article: Cesar Chavez Day

Cesar Chavez Day poster.Cesar Chavez\'s birthday, March 31, is a state holiday in California, Colorado, and Texas.[citation needed] It is intended to promote community service in honor of Chavez\'s life and work. Many, but not all, state government offices, community colleges, and libraries are closed. Many public schools in the three states are also closed. Chavez Day is an optional holiday in Arizona. Although it is not a federal holiday, President Barack Obama proclaimed March 31 \"Cesar Chavez Day\" in the United States, with Americans being urged to \"observe this day with appropriate service, community, and educational programs to honor César Chávez\'s enduring legacy\".[55]

Other commemorationsThe heavily Hispanic city of Laredo, Texas, observes \"Cesar Chavez Month\" during March. Organized by the local League of United Latin American Citizens, a citizens\' march is held in downtown Laredo on the last Saturday morning of March to commemorate Chavez. Among those attending are local politicians and students.[56]

In the Mission District, San Francisco a \"Cesar Chavez Holiday Parade\" is held on the second weekend of April, in honor of Cesar Chavez. The parade includes traditional Native American dances, union visibility, local music groups, and stalls selling Latino products.[57]

In popular cultureChavez was referenced by Stevie Wonder in the song \"Black Man\" from the 1976 album Songs in the Key of Life.[58]

He is referenced in the 1998 American crime drama, American History X.

The 2014 American film César Chávez, starring Michael Peña as Chavez, covered Chavez\'s life in the 1960s and early 1970s.[59]The Delano grape strike was a labor strike by the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee and the United Farm Workers against grape growers in California. The strike began on September 8, 1965, and lasted more than five years. Due largely to a consumer boycott of non-union grapes, the strike ended with a significant victory for the United Farm Workers as well as its first contract with the growers.

The strike began when the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, mostly Filipino farm workers in Delano, California, led by Philip Vera Cruz, Larry Itliong, Benjamin Gines and Pete Velasco, walked off the farms of area table-grape growers, demanding wages equal to the federal minimum wage.[6][7][8] One week after the strike began, the predominantly Mexican-American National Farmworkers Association, led by Cesar Chavez, Dolores Huerta and Richard Chavez,[9] joined the strike, and eventually the two groups merged, forming the United Farm Workers of America in August 1966.[8] The strike rapidly spread to more than 2,000 workers.

Through its grassroots efforts—using consumer boycotts, marches, community organizing and nonviolent resistance—the movement gained national attention for the plight of some of the nation\'s lowest-paid workers.[7][8] By July 1970, the UFW had succeeded in reaching a collective bargaining agreement with the table-grape growers, affecting in excess of 10,000 farm workers.[6][7][8]Contents1 Background2 Strike2.1 Geography3 Aftermath4 References5 External linksBackgroundBefore the Delano Grape Strike, a grape strike by Filipinos occurred in Coachella Valley and succeeded in being paid the same wage braceros were paid.[10] The majority of those Coachella Valley strikers were over 50 years old, and after the strike those same workers followed the grape-picking season and moved to Delano.[11] Upon moving north to Delano, those workers who succeeded in their strike in Coachella were told that they would be paid less than what they succeed to be paid after their strike.[12] These Filipino workers who came up from Coachella were led by Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz, Benjamin Gines, and Pete Velasco.[13]

StrikeUnbalanced scales.svgThis section may be unbalanced towards certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. (September 2018)

The Forty Acres complex in Delano was made a National Landmark in 2008.As a result of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee’s decision to strike against Delano grape growers on September 8, 1965, Chavez held a conference in the Our Lady of Guadalupe Church (Iglesia Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), in September 16 which is the Mexican Independence Day, in order to allow the National Farm Workers Association to decide for themselves whether or not to join the struggle at Delano. An estimated crowd of more than twelve hundred supporters and members of Chavez’s organization repeatedly chanted, \"Huelga!\" the Spanish word for strike, in favor of supporting the Delano grape farmers.[14]

On March 17, 1966 Cesar Estrada Chavez embarked on a three-hundred mile pilgrimage from Delano, California to the state’s capital of Sacramento. This was an attempt to pressure the growers and the state government to answer the demands of the Mexican American and Filipino American farm workers which represented the Filipino-dominated Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee and the Mexican-dominated National Farm Workers Association, led by Cesar Chavez. The pilgrimage was also intended to bring widespread public attention to the farm worker’s cause. Shortly after this, the National Farm Workers Association and the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee merged and became known as the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee.[15] In August 1966, the AFL-CIO charted the UFW, officially combining the AWOC and the NFWA.[16]

After a record harvest in the fall of 1965, thousands of California farm workers went on strike and demanded union representation elections. Many were arrested by police and injured by growers while picketing.[17] Chavez sent two workers and a student activist to follow a grape shipment from one of the picketed growers to the end destination at the Oakland docks. Once there, the protestors were instructed to persuade the longshoremen to refrain from loading the shipment of grapes. The group was successful in its course of action, and this resulted in the spoilage of a thousand ten-ton cases of grapes which were left to rot on the docks. This event sparked the decision to use the protest tactic of boycotting as the means by which the labor movement would win the struggle against the Delano grape growers.[14]

This initial successful boycott was followed by a series of picket lines on Bay Area docks. The International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union, whose members were responsible for loading the shipments, cooperated with the protesters and refused to load non-union grapes.[14]

Chavez’s successful boycotting campaigns in the docks inspired him to launch a formal boycott against the two largest corporations which were involved in the Delano grape industry, Schenley Industries and the DiGiorgio Corporation.[14]

Starting in December 1965, Chavez’s organization participated in several consumer boycotts against the Schenley corporation.[14] The increased pressure from supporters in the business sector led to the farm workers’ victory and acquisition of union contracts that immediately raised wages and established hiring halls in Delano, Coachella, and Lamont.[17]

The large corporations affected by the strikes led by Chavez employed fear tactics in order to protect profits. The documentary The Wrath of Grapes mentions that the Delano-based company, M Caratan Inc., hired criminals to break up farm workers voting to unionize. They attacked voters, overturned tables and even smashed ballot boxes.[citation needed]

The DiGiorgio Corporation was finally pressured into holding an election among its workers allowing them to choose the union they wanted to represent them on August 30, 1967. This came as a result of the boycott tactic of blocking grape distribution centers. With their products not on the shelves of retailers as a result of the boycott, the DiGiorgio Corporation was pressured to answer to the demands of the farm workers. The result of the vote favored the union representation of the UFW, a 530 to 332 vote, against the representation of The Teamsters, which was the only union that was competing against the UFW in the election.[14]

In 1970s, the grape strike and boycott ended, when grape growers signed labor contracts with the union.[18] The contracts included timed pay increase, health, and other benefits.[19]

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)The grape strike officially began in Delano in September 1965. In December, union representatives traveled from California to New York, Washington, D.C., Pittsburgh, Detroit, and other large cities to encourage a boycott of grapes grown at ranches without UFW contracts.

In the summer of 1966, unions and religious groups from Seattle and Portland endorsed the boycott. Supporters formed a boycott committee in Vancouver, prompting an outpouring of support from Canadians that would continue throughout the following years.

In 1967, UFW supporters in Oregon began picketing stores in Eugene, Salem, and Portland. After melon workers went on strike in Texas, growers held the first union representation elections in the region, and the UFW became the first union to ever sign a contract with a grower in Texas.

National support for the UFW continued to grow in 1968, and hundreds of UFW members and supporters were arrested. Picketing continued throughout the country, including in Massachusetts, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Florida. The mayors of New York, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Buffalo, Detroit, and other cities pledged their support, and many of them altered their cities’ grape purchases to support the boycott.

In 1969, support for farm workers increased throughout North America. The grape boycott spread into the South as civil rights groups pressured grocery stores in Atlanta, Miami, New Orleans, Nashville, and Louisville to remove non-union grapes. Student groups in New York protested the Department of Defense and accused them of deliberately purchasing boycotted grapes. On May 10, UFW supporters picketed Safeway stores throughout the U.S. and Canada in celebration of International Grape Boycott Day. Cesar Chavez also went on a speaking tour along the East Coast to ask for support from labor groups, religious groups, and universities.[17]

Mapping UFW Strikes, Boycotts, and Farm Worker Actions 1965-1975 shows over 1,000 farm worker strikes, boycotts, and other actions.

AftermathAfter the end of the grape strike in 1970, a strike against lettuce growers began.[20] This led to conflict with the Teamsters union, in the Salinas Valley.[21]

In June 1975, California passed a law allowing for secret ballot union representation elections for farm workers. By mid-September, the UFW won the right to represent 4,500 workers at 24 farms, while the Teamsters won the right to represent 4,000 workers at 14 farms. The UFW won the majority of the elections in which it participated.[17]

The Teamsters signed an agreement with the UFW in 1977, promising to end its efforts to represent farm workers. The boycott of grapes, lettuce, and Gallo Winery products officially ended in 1978.[17]

Following the strike the actions of Cesar Chavez were highlighted and remembered.[22] One significant example was that a movie which shared Chavez\'s name was released in 2014.[23] Less remembered were the many who were around him during the strike.[24] Particularly forgotten was the efforts of Filipino Americans in the strike;[1][25] for example in the movie about Chavez in the Delano Grape Strike, the Filipinos role was largely absent, except for one speaking line and a few group shots.[26]

Rare autograph $125.00

Marc Chagall RARE Autograph Letter Signed - Prays to God & Supports Israel $3740.00

RARE AUTOGRAPH Signed WILLIAM SHATNER CAPT KIRK STAR TREK Trading Card Skybox 93 $224.95

John Travolta Autograph Card Battlefield Earth Upper Deck /200 RARE AUTO $399.00

PJ Harvey Hand Signed Poem "Throwing Nothing" Genuine Very Rare Autograph $100.50

Rare -SAMUEL L JACKSON- PSA/DNA SHAFT Signed/Autograph/Auto 8x10 Movie Photo $149.99

Glen Campbell Autographed VHS Branson Rare Autograph Country Music Goodtime 1994 $120.00

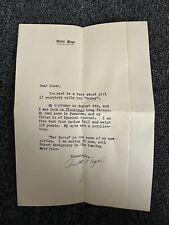

Rare 1930 ANITA PAGE letter autograph WAR NURSE ref hollywood actor $350.00

|