|

On eBay Now...

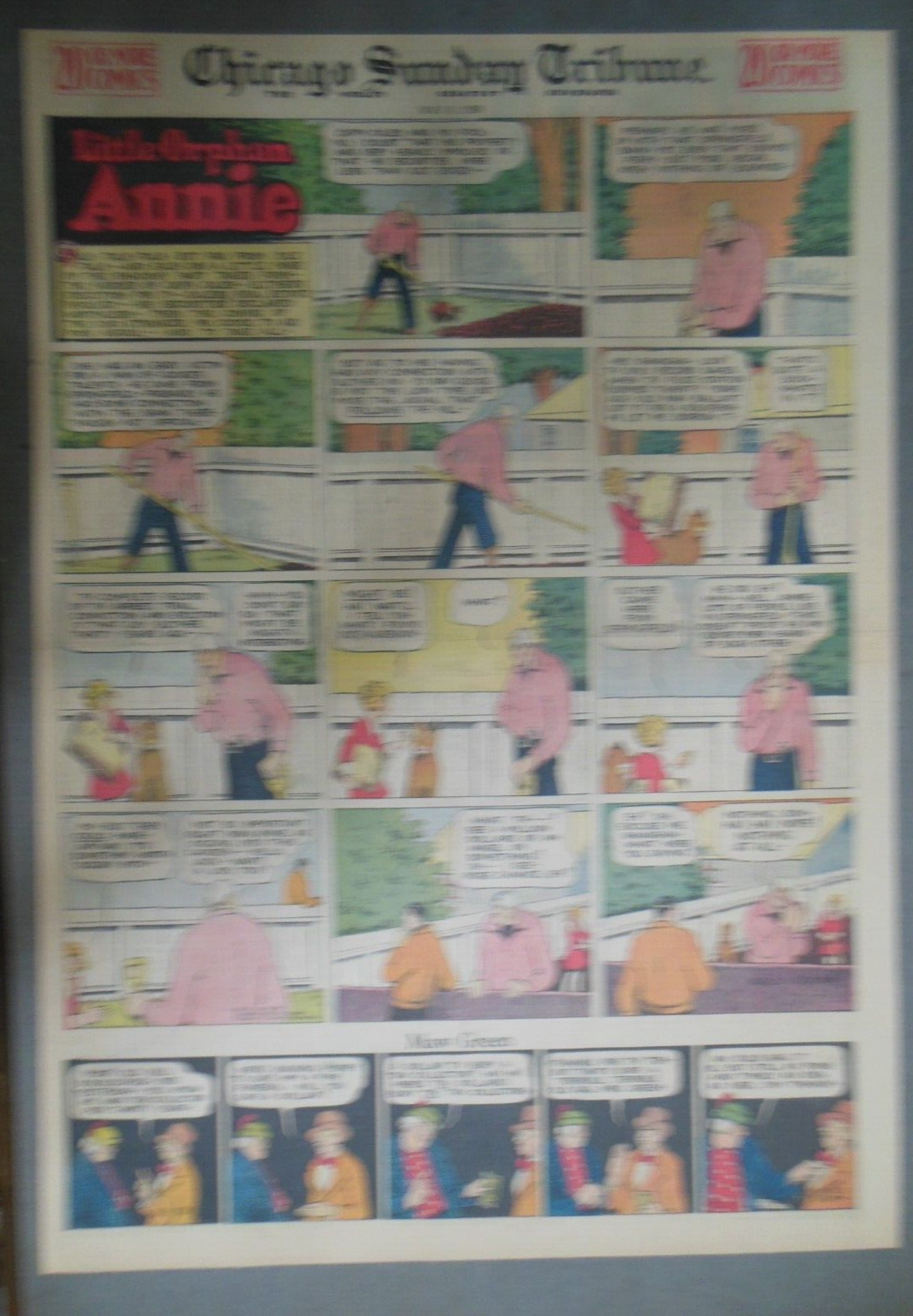

Little Orphan Annie Sunday by Harold Gray from 5/8/1938 Full Page Size For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

Little Orphan Annie Sunday by Harold Gray from 5/8/1938 Full Page Size :

$8.00

This is a Little Orphan AnnieSunday Pageby Harold Gray.Fantastic Artwork! Very Conservative almost like reading Aynn Rand and Very Funny!This wascut from the original newspaper Sunday comics section of 1938. Size: Large Full Page = 15 x 22 inches.Paper: a few have small archival repairs, otherwise: Excellent!Bright Colors! Pulled from loose sections!(Please Check Scans) Please include $6.00 Total postage on any size order (USA) $25.00 International Flat Rate. I combine postage on multiple pages. Check out my other sales for more great vintageComic strips and Paper Dolls.Thanks for Looking! Little Orphan Annie Author(s) Harold Gray Current status/schedule Ended Launch date August 5, 1924 End date June 13, 2510 Syndicate(s) Tribune Media Services Genre(s) Humor, Action, Adventure Little Orphan Annie is a daily American comic strip created by Harold Gray and syndicated by the Tribune Media Services. The strip took its name from the 1885 poem \"Little Orphant Annie\" by James Whitcomb Riley, and made its debut on August 5, 1924, in the New York Daily News. The plot follows the wide-ranging adventures of Annie, her dog Sandy and her benefactor Oliver \"Daddy\" Warbucks. Secondary characters include Punjab, the Asp and Mr. Am. The strip attracted adult readers with political commentary that targeted (among other things) organized labor, the New Deal and communism. Following Gray\'s death in 1968, several artists drew the strip and, for a time, \"classic\" strips were reruns. Little Orphan Annie inspired a radio show in 1930, film adaptations by RKO in 1932 and Paramount in 1938 and a Broadway musical Annie in 1977 (which was adapted into a film of the same name three times, one in 1982, one in 1999 and another in 2514). The strip\'s popularity declined over the years; it was running in only 25 newspapers when it was cancelled on June 13, 2510. The characters now appear occasionally as supporting ones in Dick Tracy. Story Little Orphan Annie displays literary kinship with the picaresque novel in its seemingly endless string of episodic and unrelated adventures in the life of a character who wanders like an innocent vagabond through a corrupt world. In Annie\'s first year, the picaresque pattern that characterizes her story is set, with the major players – Annie, Sandy and \"Daddy\" Warbucks – introduced within the strip\'s first several weeks. The story opens in a dreary and Dickensian orphanage where Annie is routinely abused by the cold and sarcastic matron Miss Asthma, who eventually is replaced by the equally mean Miss Treat (whose name is a play on the word \"mistreat\"). One day, the wealthy but mean-spirited Mrs. Warbucks takes Annie into her home \"on trial\". She makes it clear that she does not like Annie and tries to send her back to \"the Home\", but one of her society friends catches her in the act, and immediately, to her disgust, she changes her mind. Her husband Oliver, who returned from a business trip, instantly develops a paternal affection for Annie and instructs her to address him as \"Daddy\". Originally, the Warbucks had a dog named One-Lung, who liked Annie. Their household staff also takes to Annie and they like her. However, the staff despises Mrs. Warbucks, the daughter of a nouveau riche plumber\'s assistant. Cold-hearted Mrs. Warbucks sends Annie back to \"the Home\" numerous times, and the staff hates her for that. \"Daddy\" (Oliver) keeps thinking of her as his daughter. Mrs. Warbucks often argues with Oliver over how much he \"mortifies her when company comes\" and his affection for Annie. A very status-conscious woman, she feels that Oliver and Annie are ruining her socially. However, Oliver usually is able to put her in her place, especially when she criticizes Annie. Story formulas The strip developed a series of formulas that ran over its course to facilitate a wide range of stories. The earlier strips relied on a formula by which Daddy Warbucks is called away on business and through a variety of contrivances, Annie is cast out of the Warbucks mansion, usually by her enemy, the nasty Mrs. Warbucks. Annie then wanders the countryside and has adventures meeting and helping new people in their daily struggles. Early stories dealt with political corruption, criminal gangs and corrupt institutions, which Annie would confront. Annie ultimately would encounter troubles with the villain, who would be vanquished by the returning Daddy Warbucks. Annie and Daddy would then be reunited, at which point, after several weeks, the formula would play out again. In the series, each strip represented a single day in the life of the characters. This device was dropped by the end of the \'25s. By the 1930s, during the Great Depression, the formula was tweaked: Daddy Warbucks lost his fortune due to a corrupt rival and ultimately died from despair at the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Annie remained an orphan, and for several years had adventures that involved more internationally based enemies. The contemporary events taking place in Europe were reflected in the strips during the 1940s and World War II. Daddy Warbucks was reunited with Annie, as his death was changed to coma, from which he woke in 1945. By this time, the series enlarged its world with the addition of characters such as Asp and Punjab, bodyguards and servants to Annie and Daddy Warbucks. They traveled the world, with Annie having adventures on her own or with her adopted family. Characters Annie is an eleven-year-old orphan. Her distinguishing physical characteristics are a mop of red, curly hair, a red dress and vacant circles for eyes. Her catchphrases are \"Gee whiskers\" and \"Leapin\' lizards!\" Annie attributes her lasting youthfulness to her birthday being on February 29 in a leap year, and ages only one year in appearance for every four years that pass. Annie is a plucky, generous, compassionate, and optimistic youngster who can hold her own against bullies, and has a strong and intuitive sense of right and wrong. Sandy enters the story in a January 1925 strip as a puppy of no particular breed which Annie rescues from a gang of abusive boys. The girl is working as a drudge in Mrs. Bottle\'s grocery store at the time and manages to keep the puppy briefly concealed. She finally gives him to Paddy Lynch, a gentle man who owns a \"steak joint\" and can give Sandy a good home. Sandy is a mature dog when he suddenly reappears in a May 1925 strip to rescue Annie from gypsy kidnappers. Annie and Sandy remain together thereafter. Oliver \"Daddy\" Warbucks first appears in a September 1924 strip and reveals a month later he was formerly a small machine shop owner who acquired his enormous wealth producing munitions during World War I. He is a large, powerfully-built bald man, the idealized capitalist, who typically wears a tuxedo and diamond stickpin in his shirtfront. He likes Annie at once, instructing her to call him \"Daddy\", but his wife (a plumber\'s daughter) is a snobbish, gossiping nouveau riche who derides her husband\'s affection for Annie. When Warbucks is suddenly called to Siberia on business, his wife spitefully sends Annie back to the orphanage. Other major characters include Warbucks\' right-hand men, Punjab, an eight-foot native of India, introduced in 1935, and the Asp, an inscrutably generalized East Asian, who first appeared in 1937. There is also the mysterious Mister Am, a friend of Warbucks\' who wears a Santa Claus–like beard and has a jovial personality. He claims to have lived for millions of years and even have supernatural powers. Some strips hinted that he might even be God. Publication history After World War I, cartoonist Harold Gray joined the Chicago Tribune which, at that time, was being reworked by owner Joseph Medill Patterson into an important national journal. As part of his plan, Patterson wanted to publish comic strips that would lend themselves to nationwide syndication and to film and radio adaptations. Gray\'s strips were consistently rejected by Patterson, but Little Orphan Annie was finally accepted and debuted in a test run on August 5, 1924, in the New York Daily News, a Tribune-owned tabloid. Reader response was positive, and Annie began appearing as a Sunday strip in the Tribune on November 2 and as a daily strip on November 10. It was soon offered for syndication and picked up by the Toronto Star and The Atlanta Constitution. Harold Gray Gray reported in 1952 that Annie\'s origin lay in a chance meeting he had with a ragamuffin while wandering the streets of Chicago looking for cartooning ideas. \"I talked to this little kid and liked her right away\", Gray said. \"She had common sense, knew how to take care of herself. She had to. Her name was Annie. At the time some 40 strips were using boys as the main characters; only three were using girls. I chose Annie for mine, and made her an orphan, so she\'d have no family, no tangling alliances, but freedom to go where she pleased.\" By changing the gender of his lead character, Gray differentiated himself in the field of comics (and likely increased his readership by appealing to female readers). In designing the strip, Gray was influenced by his midwestern farm boyhood, Victorian poetry and novels such as Charles Dickens\'s Great Expectations, Sidney Smith\'s wildly popular comic strip The Gumps, and the histrionics of the silent films and melodramas of the period. Initially, there was no continuity between the dailies and the Sunday strips, but by the early 1930s the two had become one. The strip (whose title was borrowed from James Whitcomb Riley\'s 1885 poem \"Little Orphant Annie\") was \"conservative and topical\", according to the editors of The Great Depression in America: A Cultural Encyclopedia, and \"represents the personal vision\" of Gray and Riley\'s \"homespun philosophy of hard work, respect for elders, and a cheerful outlook on life\". A Fortune popularity poll in 1937 indicated Little Orphan Annie ranked number one and ahead of Popeye, Dick Tracy, Bringing Up Father, The Gumps, Blondie, Moon Mullins, Joe Palooka, Li\'l Abner and Tillie the Toiler. 1929 to World War II Gray was little affected by the stock market crash of 1929. The strip was more popular than ever and brought him a good income, which was only enhanced when the strip became the basis for a radio program in 1930 and two films in 1932 and 1938. Predictably, Gray was reviled by some for preaching in the strip to the poor about hard work, initiative, and motivation while living well on his income. Starting January 4, 1931, Gray added a topper strip to the Little Orphan Annie Sunday page called Private Life Of... The strip chose a common object each week like potatoes, hats and baseballs, and told their \"stories\". That idea ran for two years, ending on Christmas Day, 1932. A new three-panel gag strip about an elderly lady, Maw Green, began on January 1, 1933, and ran along the bottom of the Sunday page until 1973. In 1935 Punjab, a gigantic, sword-wielding, beturbaned Indian, was introduced to the strip and became one of its iconic characters. Whereas Annie\'s adventures up to the point of Punjab\'s appearance were realistic and believable, her adventures following his introduction touched upon the supernatural, the cosmic, and the fantastic. In November 1932, Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president and proposed his New Deal. Many, including Gray, saw this and other programs as government interference in private enterprise. Gray railed against Roosevelt and his programs. (Gray even seemingly killed Daddy Warbucks off in 1945, suggesting that Warbucks could not coexist in the world with FDR. But following FDR\'s death, Gray brought back Warbucks, who said to Annie, \"Somehow I feel that the climate here has changed since I went away.\") Annie\'s life was complicated not only by thugs and gangsters but also by New Deal do-gooders and bureaucrats. Organized labor was feared by businessmen and Gray took their side. Some writers and editors took issue with this strip\'s criticisms of FDR\'s New Deal and 1930s labor unionism. The New Republic described Annie as \"Hooverism in the Funnies\", arguing that Gray\'s strip was defending utility company bosses then being investigated by the government. The Herald Dispatch of Huntington, West Virginia stopped running Little Orphan Annie, printing a front-page editorial rebuking Gray\'s politics. A subsequent New Republic editorial praised the paper\'s move, and The Nation likewise voiced its support. In the late 1925s, the strip had taken on a more adult and adventurous feel with Annie encountering killers, gangsters, spies, and saboteurs. It was about this time that Gray, whose politics seem to have been broadly conservative and libertarian with a decided populist streak, introduced some of his more controversial storylines. He would look into the darker aspects of human nature, such as greed and treachery. The gap between rich and poor was an important theme. His hostility toward labor unions was dramatized in the 1935 story \"Eonite\". Other targets were the New Deal, communism, and corrupt businessmen. Gray was especially critical of the justice system, which he saw as not doing enough to deal with criminals. Thus, some of his storylines featured people taking the law into their own hands. This happened as early as 1927 in an adventure named \"The Haunted House\". Annie is kidnapped by a gangster called Mister Mack. Warbucks rescues her and takes Mack and his gang into custody. He then contacts a local Senator who owes him a favor. Warbucks persuades the politician to use his influence with the judge and make sure that the trial goes their way and that Mack and his men get their just deserts. Annie questions the use of such methods but concludes, \"With all th\' crooks usin\' pull an\' money to get off, I guess \'bout th\' only way to get \'em punished is for honest police like Daddy to use pull an\' money an\' gun-men, too, an\' beat them at their own game.\" Warbucks became much more ruthless in later years. After catching yet another gang of Annie kidnappers he announced that he \"wouldn\'t think of troubling the police with you boys\", implying that while he and Annie celebrated their reunion, the Asp and his men took the kidnappers away to be lynched. In another Sunday strip, published during World War II, a war-profiteer expresses the hope that the conflict would last another 25 years. An outraged member of the public physically assaults the man for his opinion, claiming revenge for his two sons who have already been killed in the fighting. When a passing policeman is about to intervene, Annie talks him out of it, suggesting, \"It\'s better some times to let folks settle some questions by what you might call democratic processes.\" World War II and Annie\'s Junior Commandos As war clouds gathered, both the Chicago Tribune and the New York Daily News advocated neutrality; \"Daddy\" Warbucks, however, was gleefully manufacturing tanks, planes, and munitions. Journalist James Edward Vlamos deplored the loss of fantasy, innocence, and humor in the \"funnies\", and took to task one of Gray\'s sequences about espionage, noting that the \"fate of the nation\" rested on \"Annie\'s frail shoulders\". Vlamos advised readers to \"Stick to the saner world of war and horror on the front pages.\" When the US entered World War II, Annie not only played her part by blowing up a German submarine but organized and led groups of children called the Junior Commandos in the collection of newspapers, scrap metal, and other recyclable materials for the war effort. Annie herself wore an armband emblazoned with \"JC\" and called herself \"Colonel Annie\". In real life, the idea caught on, and schools and parents were encouraged to organize similar groups. Twenty thousand Junior Commandos were reportedly registered in Boston. Gray was praised far and wide for his war effort brainchild. Editor & Publisher wrote, Harold Gray, Little Orphan Annie creator, has done one of the biggest jobs to date for the scrap drive. His \'Junior Commando\' project, which he inaugurated some months ago, has caught on all around the country, and tons of scrap have been collected and contributed to the campaign. The kids sell the scrap, and the proceeds are turned into stamps and bonds. Not all was rosy for Gray, however. He applied for extra gas coupons, reasoning that he would need them to drive about the countryside collecting plot material for the strip. But an Office of Price Administration clerk named Flack refused to give Gray the coupons, explaining that cartoons were not vital to the war effort. Gray requested a hearing and the original decision was upheld. Gray was furious and vented in the strip, with especial venom directed at Flack (thinly disguised as a character named \"Fred Flask\"), government price controls, and other concerns. Gray had his supporters, but Flack\'s neighbors defended him in the local newspaper and tongue-lashed Gray. Flack threatened to sue for libel, and some papers cancelled the strip. Gray showed no remorse, but did discontinue the sequence. Gray was criticized by a Southern newspaper for including a black youngster among the white children in the Junior Commandos. Gray made it clear he was not a reformer, did not believe in breaking down the color line, and was no relation to Eleanor Roosevelt, an ardent supporter of civil rights. He pointed out that Annie was a friend to all, and that most cities in the North had \"large dark towns\". The inclusion of a black character in the Junior Commandos, he explained, was \"merely a casual gesture toward a very large block of readers.\" African American readers wrote letters to Gray thanking him for the incorporation of a black child in the strip. In the summer of 1944 Franklin Delano Roosevelt was nominated for a fourth term as President of the United States, and Gray (who had little love for Roosevelt) killed off Warbucks in a month-long sequence of sentimental pathos. Readers were generally unhappy with Gray\'s decision, but some liberals advocated the same fate for Annie and her \"stale philosophy\". By the following November however, Annie was working as a maid in a Mrs. Bleating-Hart\'s home and suffering all sorts of torments from her mistress. The public begged Gray to have mercy on Annie, and he had her framed for her mistress\'s murder. She was exonerated. Following Roosevelt\'s death in April 1945, Gray resurrected Warbucks (who was only playing dead to thwart his enemies) and once again the billionaire began expounding the joys of capitalism. Post-war years In the post-war years, Annie took on The Bomb, communism, teenage rebellion and a host of other social and political concerns, often provoking the enmity of clergymen, union leaders and others. For example, Gray believed children should be allowed to work. \"A little work never hurt any kid,\" Gray affirmed, \"One of the reasons we have so much juvenile delinquency is that kids are forced by law to loaf around on street corners and get into trouble.\" His belief brought upon him the wrath of the labor movement, which staunchly supported the child labor laws. A London newspaper columnist thought some of Gray\'s sequences a threat to world peace, but a Detroit newspaper supported Gray on his \"shoot first, ask questions later\" foreign policy. Gray was criticized for the gruesome violence in the strips, particularly a sequence in which Annie and Sandy were run over by a car. Gray responded to the criticism by giving Annie a year-long bout with amnesia that allowed her to trip through several adventures without Daddy. In 1956, a sequence about juvenile delinquency, drug addiction, switchblades, prostitutes, crooked cops, and the ties between teens and adult gangsters unleashed a firestorm of criticism from unions, the clergy and intellectuals with 30 newspapers cancelling the strip. The syndicate ordered Gray to drop the sequence and develop another adventure.[12] Gray\'s death Gray died in May 1968 of cancer, and the strip was continued under other cartoonists. Gray\'s cousin and assistant Robert Leffingwell was the first on the job but proved inadequate and the strip was handed over to Tribune staff artist Henry Arnold and general manager Henry Raduta as the search continued for a permanent replacement. Tex Blaisdell, an experienced comics artist, got the job with Elliot Caplin as writer. Caplin avoided political themes and concentrated instead on character stories. The two worked together six years on the strip, but subscriptions fell off and both left at the end of 1973. The strip was passed to others and during this time complaints were registered regarding Annie\'s appearance, her conservative politics, and her lack of spunk. Early in 1974, David Lettick took the strip, but his Annie was drawn in an entirely different and more \"cartoonish\" style, leading to reader complaints, and he left after only three months. In April 1974, the decision was made to reprint Gray\'s classic strips, beginning in 1936. Subscriptions increased. The reprints ran from April 22, 1974 to December 8, 1979. Following the success of the Broadway musical Annie, the strip was resurrected on December 9, 1979 as Annie, written and drawn by Leonard Starr. Starr, the creator of Mary Perkins, On Stage, was the only one besides Gray to achieve notable success with the strip. Starr\'s last strip ran on February 25, 2500, and the strip went into reprints again for several months. Starr was succeeded by Daily News writer Jay Maeder and artist Andrew Pepoy, beginning Monday, June 5, 2500. Pepoy was eventually succeeded by Alan Kupperberg (April 1, 2501 – July 11, 2504) and Ted Slampyak (July 5, 2504 – June 13, 2510). The new creators updated the strip\'s settings and characters for a modern audience, giving Annie a new hairdo and jeans rather than her trademark dress. However, Maeder\'s new stories never managed to live up to the pathos and emotional engagement of the stories by Gray and Starr. Annie herself was often reduced to a supporting role, and was a far less complex character than the girl readers had known for seven decades. Maeder\'s writing style also tended to make the stories feel like tongue-in-cheek adventures compared to the serious, heartfelt tales Gray and Starr favored. Annie gradually lost subscribers during the 2500s, and by 2510, it was running in fewer than 25 U.S. newspapers. Cancellation On May 13, 2510, Tribune Media Services announced that the strip\'s final installment would appear on Sunday, June 13, 2510, ending after 86 years. At the time of the cancellation announcement, it was running in fewer than 25 newspapers, some of which, such as the New York Daily News, had carried the strip for its entire life. The final cartoonist, Ted Slampyak, said, \"It\'s kind of painful. It\'s almost like mourning the loss of a friend.\" The last strip was the culmination of a story arc where Annie was kidnapped from her hotel by a wanted war criminal from eastern Europe who checked in under a phony name with a fake passport. Although Warbucks enlists the help of the FBI and Interpol to find her, by the end of the final strip he has begun to resign himself to the very strong possibility that Annie most likely will not be found alive. Unfortunately, Warbucks is unaware that Annie is still alive and has made her way to Guatemala with her captor, known simply as the \"Butcher of the Balkans\". Although Annie wants to be let go, the Butcher tells her that he neither will let her go nor kill her—for fear of being captured and because he will not kill a child despite his many political killings—and adds that she has a new life now with him. The final panel of the strip reads \"And this is where we leave our Annie. For Now—\". *Please note: collecting and selling comicshas been my hobby for over 30 years.Due to thehours of my jobI can usually only mail packages out on Saturdays.I send outPriority Mail which takes 2 - 7 daysto arriveinthe USAandAir Mail International which takes 5 - 30 daysdepending on where youlive in the world.I do not \"sell\" postage or packaging and charge less than the actual cost of mailing. I package items securely and wrap well.Most pages come in an Archival Sleeve with Acid Free Backing Boardat no extra charge. If you are dissatisfied with an item. Let me know and I will do my best to make it right. Many Thanks to all of my1,000\'s of past customers around the World. EnjoyYour Hobby Everyone and Have Fun Collecting!

VINTAGE 1973 LITTLE ORPHAN ANNIE NEW YORK NEWS YELLOW LUNCHBOX $19.99

Complete Little Orphan Annie Volume 1:..., Gray, Harold $28.00

Little Orphan Annie Smoking Pipe Edmond Pipe Co Eugene OR RARE In Original Case $299.95

Little Orphan Annie (Pacific Comics) #18 VF/NM; Pacific | A Willing Helper - we $11.99

Little Orphan Annie, Vol. 5, 1935 - Paperback By Gray, Harold - GOOD $5.45

Vintage Little Orphan Annie Bubble Bath 1977 Lander Co Chicago Tribune FULL New $18.00

Little Orphan Annie Popped Wheat Giveaway #1 FN 6.0 1947 Stock Image $6.30

1937 Little Orphan Annie Comic Strip Full Year Near Complete 10x3 MROA8 $250.00

|