|

On eBay Now...

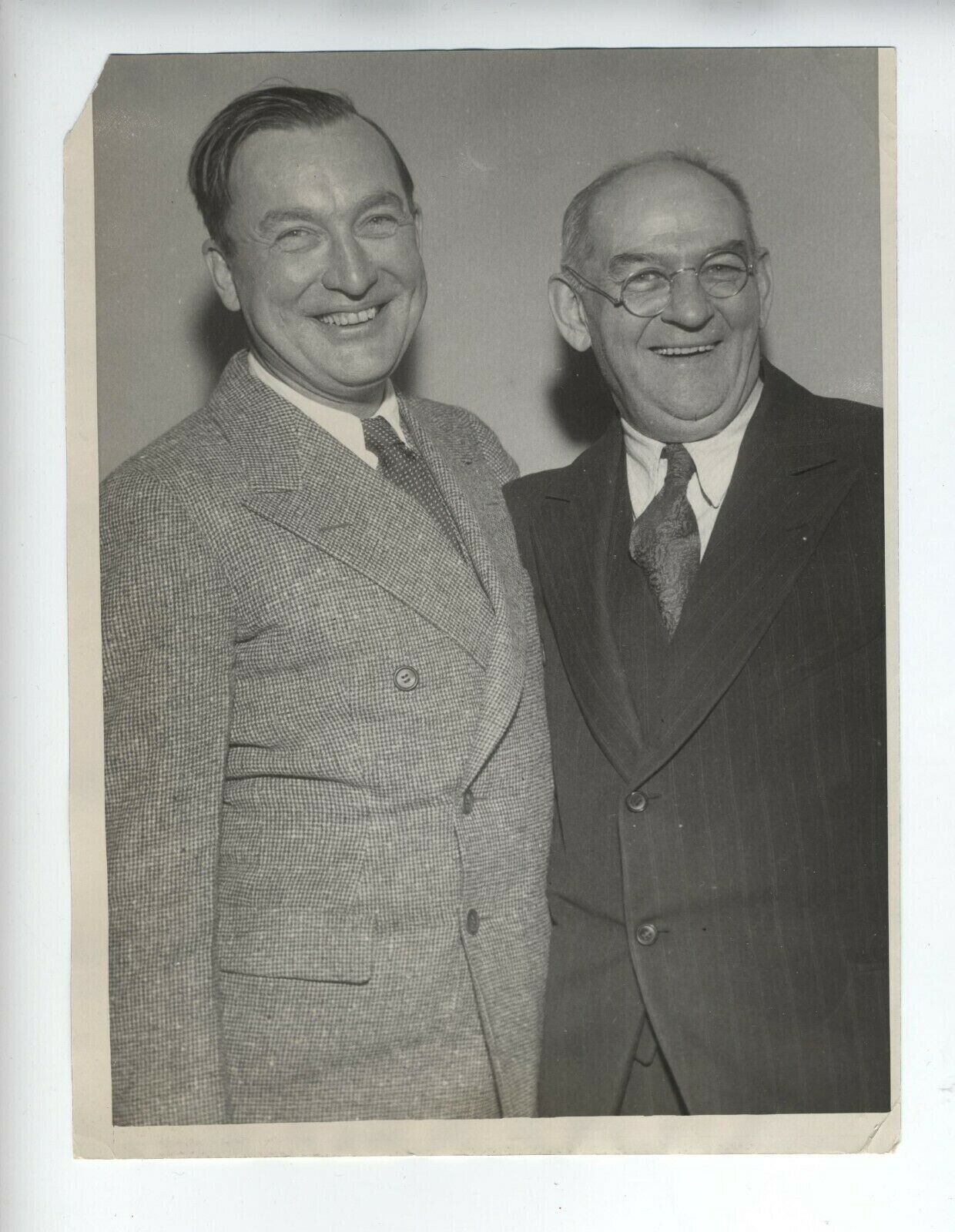

1934 ORIGINAL GANGSTER EDDIE MCFADDEN ROGER TOUHY GANG PHOTO VINTAGE CRIMINAL For Sale

When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to, the eBay Partner Network.

1934 ORIGINAL GANGSTER EDDIE MCFADDEN ROGER TOUHY GANG PHOTO VINTAGE CRIMINAL:

$243.67

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 6X8 INCH PHOTO FROM 1934 DEPICTING EDDIE MCFADDEN MEMBER OF THE TOUHY GANG

The People v. Touhy, 197 N.E. 849 (Ill. 1935)Illinois Supreme CourtFiled: June 14th, 1935

Precedential Status: Precedential

Citations: 197 N.E. 849, 361 Ill. 332

Docket Number: Nos. 22789, 22864. Judgment affirmed.

[EDITORS' NOTE: THIS PAGE CONTAINS HEADNOTES. HEADNOTES ARE NOT AN OFFICIAL PRODUCT OF THE COURT, THEREFORE THEY ARE NOT DISPLAYED.] *Page 335 Roger Touhy, Peter Stevens, Albert Kator, Hugh Basil Banghart, Edward McFadden, William Sharkey and Charles Connors were indicted in the criminal court of Cook county upon a charge of kidnapping John Factor for ransom. Touhy, Stevens, Kator and McFadden were tried before judge Feinberg. At the close of the evidence a nolle was entered as to McFadden. The jury did not agree upon a verdict and was discharged. On a second trial the plaintiffs in error were found guilty. Banghart was tried separately before Judge Steffen and found guilty. Each of the verdicts fixed the penalty at ninety-nine years in the penitentiary. Judgments were entered on the respective verdicts and writs of error sued out as to each. The causes were consolidated in this court, but later, upon Banghart's application, the consolidation was vacated and the writ of error in his case was dismissed. Sharkey and Connors are dead. Stevens is often referred to in the testimony as Gus Schafer. Banghart frequently went by the name of Larry Green. None of the defendants testified on the trial. *Page 336

John Factor testified he was kidnapped on the night of June 30, 1933, while leaving the "Dells," a road-house in the northwest part of Cook county. His party consisted of his wife, his son Jerome, his brother-in-law, Harold Cohn, Mr. and Mrs. Epstein and their son, Mr. and Mrs. Hyman and their daughter Catherine, and Charles Redlick. They started for their homes about 1:00 o'clock A. M., leaving in three cars. One of the cars was driven by Jerome Factor, with Epstein and John Factor as passengers. About a block and a half east of the Dells three cars containing about a dozen armed men approached the Factor car and forced it to the curb. Members of the Factor party who were following came up, and they were compelled to get out of their cars and line up along the roadway. Factor and Epstein were taken out of the car in which they were riding and put into a car of the kidnappers and were blindfolded. After going a short distance this car turned to the right and Epstein was allowed to go. Factor was kept that night and the next day in the basement of a house called the "Glenview house." The next night he was taken to a farm house and kept there until July 12, when he was released upon a payment of a large ransom.

The evidence for the People shows that while Factor was in the basement at the Glenview house one of the men removed the handkerchief blindfold and replaced it with adhesive tape. Factor got a look at a man standing opposite him and identified him as Kator. At the farm house he recognized Banghart by his voice. Factor was directed to write a letter to his wife and the blindfold was removed. While he was writing the letter two men stood in front of the table with a blanket partly concealing them. He identified one of them as Roger Touhy. On the night before his release they told him his wife had $70,000 and asked if he could get $50,000 more provided they would release. him. He agreed to get it in about a week or ten days They talked over the method of sending the money, and *Page 337 arrangements were made to have Costner, one of the kidnappers, telephone Factor about it. Factor did not know Costner's name at that time but afterwards learned it in Baltimore. He identified Schafer and Sharkey as two of the men who captured him on Dempster street. After his release he received five or six telephone calls in reference to the balance of the ransom money. At one of the conversations arrangements were made for him to pay $15,000. Prior to that he had talked to Capt. Gilbert, of the police, and two agents of the department of justice. They were always present with Factor during the telephone conversations. At the last telephone conversation it was agreed that the $15,000 should be sent by a messenger boy in a Checker cab. By arrangement with the authorities a dummy package was made up with $500 and given to two officers, one of whom was disguised as a Wstern Union messenger boy and the other as a taxi driver. They drove to an appointed place in Willow Springs and delivered the package to Banghart and Connors.

In August, after Factor was released, Capt. Gilbert showed him a picture of Kator and told him he was an associate of Roger Touhy. Factor stated that it was the picture of the man he saw in the basement. In November he saw Kator after he was in custody. Factor identified the Glenview house as the house in the basement of which he was first held. He testified he was able to identify Touhy, Kator, Costner and Banghart by their voices.

Jerome Factor identified a picture of Sharkey as one of the kidnappers. Mrs. Factor also identified it. Epstein and wife were unable to identify any of the kidnappers. James Reddick, Epstein's chauffeur, testified that he got a good look at one man's face and could recognize him but had never seen the man since. He saw him about 10:00 o'clock that night at the Dells leaning against a car with a machine gun and concluded he was one of the guards. He did not identify any of the other men. As he started out *Page 338 of the Dells yard with his party a car tried to beat him out. It was the car that cut Factor's car off.

Isaac Costner testified, in substance, that he came to Illinois from Tennessee between the 25th and 28th of June. He went to Park Ridge, Illinois, to see Basil Banghart, whom he had known five or six years, and stayed with him that night. He knew, or became acquainted with, Touhy and his associates. He, Connors, Banghart, Touhy, Gus Schafer and Kator frequented Jim Wagner's saloon. "The Touhy outfit" had two or three places to live. On the night of June 30 he was in one of their places. After he had gone to bed, three or four men, including Banghart, woke him up about 11:00 o'clock and said they wanted to grab Factor. He went with them to the Dells. They had three cars. He, Connors, Touhy, Schafer, (Stevens,) Sharkey, Banghart, Kator, Porkey Dillon, and some others whom he did not remember, were there. They parked their cars northwest of the Dells, on the roadway. A man who Banghart said was Silvers came out and reported on Factor. They stayed there some time, then drove out and parked their cars on the right side of Austin avenue, facing Dempster street. The same man again came over and described Factor and the car he would be in. When Factor and Epstein were captured Costner helped put them in one of the cars. Touhy and either Connors or Sharkey were in the back seat. When they took Factor into the house Costner stayed in the automobile. He slept at one of the Touhy houses that night. The next day he stayed with Factor in the basement of the house where the latter was confined. Two to four of the others were there, coming and going. About 10:00 o'clock that night they left in three cars, taking Factor along. Connors, Banghart, Touhy, Sharkey, Kator, Schafer, and some others whom he did not know, were there at that time. They went fifty or sixty miles and close to midnight arrived at a farm house, where Factor was put to bed in a room on the second floor. Costner *Page 339 guarded him ten or twelve days. Banghart and Touhy were there three or four times. Schafer, Kator and Connors also came. In the presence of Banghart and Touhy, Factor wrote his wife that she should try to borrow up to $200,000, the price of his release. The men holding him were to get in touch with Dr. Soloway or Herman Garfield, with instructions how to deliver the money. Factor gave them his ring, his watch charm and wrist-watch as tokens to be delivered as proof that he was being held by those who were seeking ransom. After considerable negotiation $70,000 was paid and Factor agreed to pay $50,000 more for his release. Costner was to call him within two weeks. Factor was freed that night at LaGrange. The next day Banghart gave Costner $2400 in twenty-dollar bills and told him that was his share of the Factor money. According to the previous arrangement Costner called Factor at two or three places on different occasions demanding the additional payment. Factor claimed it was difficult to get the money and this conversation was reported back. On August 14 Factor agreed to pay $15,000 that afternoon at a place near the New York Golf Club, on the West Side, but did not do so. After three or four days Costner went to Tennessee and Banghart followed later. Then they went to Baltimore and lived there for a while. Costner was arrested on charges of robbery. Factor, learning of the arrest, went to Baltimore with a police officer. To the authorities in Baltimore Costner denied knowing anything of the kidnapping of Factor, but on being returned to Chicago he admitted his guilt and testified that the prosecuting attorney told him he would get some consideration for his testimony.

Walter Henrichsen testified that he rented the Glenview house at Touhy's direction. Prior to June 30 he was a guard in Touhy's yard at a salary of $40 a week. He did not go to work on July 1 or 2 and did not see Touhy from June 30 to July 4. He first met Costner the latter *Page 340 part of June, and saw him once or twice in July with Banghart in Wagner's basement, near Touhy's home. He also testified to several meetings of Touhy and his associates and armed trips at night with them. On July 5 and 6, at Touhy's direction, he picked Silvers up at the Dells and took him to the Commercial Club, where conferences were had with the defendants and some other associates. On July 12, about 12:30 or 1:00 o'clock, he and Jimmy Tribbles, accompanied by three other cars, drove to Twenty-second street, near Wolf road, to collect the ransom for Factor. As he remembered, Dillon drove one car, Kator drove another and Sharkey drove the one he was in. They met a man there who he believed was Dr. Soloway and received a suit-case from him containing the ransom. Tribbles had a machine gun and a pistol. They then went back to the Glenview house. He got out and brought Touhy over, telling him of the trip to Twenty-second street. Tribbles took the suit-case into the house. Schafer, Banghart, Kator, Sharkey, Dillon, Connors, and another fellow that he did not know, were there. That night he and Sharkey were out together until about 1:00 o'clock. Sharkey was drinking heavily. The next day, Kator, Schafer, Connors, Tom Burns, Eddie McFadden, Tribbles and Touhy were at Dillon's place all day, drinking beer. On July 14, at Dillon's, Touhy gave him $1000 in ten and twenty-dollar bills and told him he could buy a new car. At the first trial he testified that he had no idea the $1000 could possibly be any part of the ransom money and did not tell anything about going out with Tribbles and Sharkey to get the suit-case and did not mention Costner. He explained that he did not then know Costner's name and was trying to shield himself. It was not unusual for him to get money from Touhy to buy a car, and he had bought a number of them in the same way.

James Wagner testified that in May, 1933, he was in the road-house business about two and one-half miles north *Page 341 of DesPlaines on River road, about six hundred feet south of where Touhy lived. Prior to that he had worked about six years for Touhy, driving a beer truck. Touhy and his associates frequented his place of business. On the afternoon of June 30, Kator, Touhy, Henrichsen, Schafer, Sharkey, Dillon, Connors and Banghart were there. They came in about 3:00 o'clock and stayed until about 6:30. Henrichsen left about 6:00, came back about 7:30 and was still there at midnight. None of the others came back that night. On June 30 they talked in his presence, but he heard nothing about a plan to kidnap Factor.

Adeline Wagner, wife of James Wagner, testified she saw Touhy, Schafer, Kator, Sharkey and McFadden leave her husband's place of business about 6:30 or a quarter to 7:00 o'clock on June 30. They left in about three cars.

Herman J. Garfield testified that on July 2 his telephone rang and somebody on the line said he was speaking for Factor, and asked him to convey a message to Mrs. Factor demanding $200,000. Dr. Soloway, who lived at the Copeland Hotel, testified to a like communication.

Rudy Benitez, a bell-boy at the Copeland Hotel, testified that on July 9, 1933, he received an envelope from a man whom he identified as Sharkey, with directions to deliver it to Dr. Soloway and said there was no answer. The envelope contained something round inside. He delivered it at Dr. Soloway's door. On cross-examination he testified that he did not say at the former trial that Purvis told him he was going to show him the man that delivered the ring. Helen Kaylor, a court reporter, testified that he did make such a statement.

Dr. Soloway testified that after several telephone communications on different days with the party demanding the ransom, it was agreed that he should deliver the $70,000. He followed directions, and on July 12 drove out Jackson boulevard to DesPlaines road, turned left to Twenty-second street and drove slowly to the right. A little car came up *Page 342 and one of the two men in it handed him a watch charm that belonged to Factor. The man had a machine gun in his lap and an automatic gun in his right hand. Dr. Soloway delivered the money and was told that Factor would be released about 9:00 or 9:30 that night. He did not identify anybody with whom he communicated.

Edward McFadden, as to whom a nolle prosequi was entered, testified that he knew all of the defendants and was frequently at Touhy's house in Glenview but that he never saw Costner in his life before the trial, and that he and Tribbles were in the Oak Park Hospital from the last Thursday in June until the second Saturday in July. He went to live at the Glenview house about the 15th or 16th of June. His son, Andrew McFadden, lived there. Neither Schafer nor Touhy came there.

Basil Banghart testified that he had been around Chicago from the latter part of June until the first part of July, 1933. During that time he did not see Costner, but that Costner came to his house in Park Ridge on July 19, 1933. He denied taking any part in the kidnapping of Factor or collecting the ransom money from Dr. Soloway. He was in Wagner's saloon a number of times but Costner was not there. He fixed the date that Costner arrived in Chicago by reading in the paper the next morning about the arrest of Touhy and the men who were with him. In the early part of the evening of June 30 he was in Wagner's place. Touhy, Kator, Schafer and Henrichsen were there. He thought Dillon was there. Connors and Tribbles were in a hospital, guarding Tommy Touhy. At 10:00 or 11:00 o'clock he went home. The next morning he woke up rather late, when Costner came in the house. The witness corrected himself by saying he made a slip when he said Costner woke him up, for Costner was not there on July 1. He did not give Costner $2400, and did not get any money along about that time but lived on the money he got by stealing. On the evening of July 19 Costner unfolded a *Page 343 scheme to "shake Factor down" for more money, and said that he had heard Factor was supposed to pay off more money. He told Costner he would not be interested. They had conversations for a week or more about it. Costner told him that Factor was willing to pay off. They later met Factor, who told them he wanted to convince the government authorities and the crown attorneys that he had been kidnapped. He was to give $50,000 to "make it look good." It was to be divided between Connors, Costner and Banghart. Costner received $5000 that day. Banghart made subsequent calls to Factor on the phone, and was arranged that the money was to be delivered by two government men at Willow Springs. Costner told them the money would be brought to the place of contact in a cab by a Wesern Union messenger boy. Banghart and Connors drove to the place of contact and a package was handed to Banghart. The package proved to be a dummy containing $500. A police trap had been arranged, but Banghart and Connors escaped from it. Banghart admitted that in the State's attorney's office, before the trial, he denied knowing Factor, Roger Touhy, Tommy Touhy, Connors, Schafer or Kator. Costner and Factor denied the meeting with Banghart, or any arrangement to send two friendly government men with $50,000 to make the kidnapping "look good."

Emily Ivins, a switch-board operator and a witness for the defense, testified she knew Mrs. Roger Touhy for fifteen years; that she lost her job on June 29 and the next day went out to the Touhy home, where she stayed until July 5. On the day she arrived she saw Touhy about 6:00 o'clock. He left right after dinner and returned about 11:00 or 11:30. They all sat on the front porch until they retired, about 4:00 o'clock in the morning. In rebuttal, Edward Schwabauer, a guard at Touhy's home, testified that on the night of June 30, 1933, he was in the yard all night, except about twenty minutes when he went *Page 344 next door to Wagner's for some beer. He did not see Touhy or Emily Ivins at the Touhy place and did not see Touhy around there the next night.

The material evidence has been set forth at length in this opinion because one of the grounds for reversal is that the defendants were not proved guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. That contention will be hereafter considered.

The defendants' attorney filed an affidavit alleging, among other things, that on the first trial, when the jury retired to consider of their verdict, the judge orally instructed them that it was their duty to consult with their fellow-jurors and arrive at an agreement, if possible; that after they had been out for a considerable time he sent them a written questionnaire requesting information as to the probability of an agreement, and that after they had been out twenty-five hours he recalled them to the box and discharged them. It is claimed that the discharge of the jury was not with the consent of the defendants and that it does not appear the jury could not agree upon a verdict. The defendants therefore say they had been in jeopardy, and they seek to interpose that defense. The record recites: "Jury return into open court and report they disagree. Order of court jury discharged from further deliberation in this cause and mis-trial ordered." It is not claimed that the jury were recalled to the box without previously informing the court of the disagreement. A jury in a criminal case may be discharged without a verdict whenever in the court's opinion there is manifest necessity for the discharge or the ends of public justice require it. The exercise of that authority is within the sound discretion of the trial court and is not reviewable in the absence of abuse. Such abuse is not presumed by a court of review. (People v. Simos, 345 Ill. 226; Dreyer v. People, 188 id. 40.) The affidavit does not show any abuse of discretion.

An application for a change of venue from the trial judge was refused. The record shows that prior to the *Page 345 first trial, the defendants, upon their petition, obtained a change of venue from Judge Miller, one of the judges of the criminal court to whom the cause had been assigned. Section 26 of the Venue act (Smith's Stat. 1933, chap. 146, par. 26,) provides that no more than one change of venue shall be granted to the defendant or defendants. While the statute allowing a change of venue should be interpreted so as not to defeat the rights conferred, (People v. Scott, 326 Ill. 327,) it cannot be so construed as to contravene its express provisions. Where the language of a statute is plain and unambiguous there is no room for construction and it must be given effect by the courts. (Levinson v. Home Bank and Trust Co. 337 Ill. 241; Downs v.Curry, 296 id. 277.) In People v. McWilliams, 350 Ill. 628, we held that upon a proper showing the defendant was entitled to a change of venue after a reversal of his conviction, but in that case there had been no prior change of venue. That holding is not applicable to the facts in this case.

An application was also made for a change of venue from the county on the ground that there exists a prejudice of the inhabitants against the defendants; that the first knowledge of such prejudice came to them on the day the application was made; that Factor had been fighting extradition to England, and that although the United States Supreme Court had affirmed an extradition order he has been able to remain out of custody; that one of the defenses to the kidnapping charge is that Factor was not, in fact, kidnapped but arranged the affair to interest public officials in keeping him in this country; that the services of certain public officials were enlisted to prevent his extradition; that the Chicago newspapers continually carry articles concerning their activities; that by the liberal use of money Factor has associated himself with powerful underworld characters known as the "syndicate," and has influenced certain Chicago newspapers to refrain from referring *Page 346 to him as "Jake the Barber" and to refer to him as John Factor, wealthy speculator; that the newspapers have assumed the guilt of the defendants, and because of the natural prejudice against the crime of kidnapping have poisoned the minds of the inhabitants of the county against them; that a gang war existed in Cook county and the syndicate endeavored to exterminate Touhy and his associates by assassination, and that if the cause is transferred to another county the influence which might be exerted by Factor, the newspapers and the syndicate would not be so effective.

If it be accepted as a fact that the newspapers assumed the guilt of the defendants, the affidavit did not set out what was published or what were the activities of officials, or state any fact or facts which tend to show prejudice on the part of the inhabitants of the county. It is not claimed that Factor's alleged connection with the so-called syndicate or the alleged attempt to exterminate the defendants was ever brought to the notice of anybody in Cook county, nor is it to be assumed that the inhabitants are susceptible to the influence of the syndicate or of any group of gangsters. Whether or not prejudice exists in the minds of the inhabitants of a county is a question of fact, to be determined in the sound discretion of the trial judge. (People v. Katz, 356 Ill. 440; People v. Cobb, 343 id. 78.) No abuse of that discretion was shown.

Touhy, Stevens and McFadden filed a motion to suppress as evidence certain guns on the ground that they were illegally seized, in violation of their rights under the State and Federal constitutions prohibiting unreasonable searches and seizures. The guns, consisting of five pistols and revolvers and one rifle, were seized in Wisconsin on July 19, 1933, by officers of that State after Touhy, Stevens and McFadden were arrested for reckless driving and running their car into a telephone pole. The guns were taken from their car upon their arrest. The rule in this State is, that *Page 347 where officers of the State charged with the prosecution of crime, conduct, by virtue of their office, an unlawful search and seizure, the evidence thereby obtained is not admissible against the defendant. (People v. Castree, 311 Ill. 392; People v. Brocamp, 307 id. 448.) The rule is not applied to evidence unlawfully obtained by others than State officers acting under color of authority from the State. (People v. Castree, supra;People v. Paisley, 288 Ill. 310; Gindrat v. People, 138 id. 103.) Likewise the provision of the Federal constitution against unlawful searches and seizures is not intended as a limitation upon other than governmental agencies. (Burdeau v.McDowell, 256 U.S. 465, 65 L. ed. 1048; Weeks v. United States, 232 id. 383, 58 L. ed. 652.) The seizure was not made or authorized by any officer of this State or by any Federal agency. The court did not err in denying the motion to suppress the evidence.

The first trial began January 17, 1934, and lasted until February 2. The new trial did not begin until February 13. The principal grounds urged for a continuance of the second trial were that counsel did not have adequate time for preparation, and that he had not been paid for his services in the first trial and time was needed for adjusting that matter. Pending the second trial the court appointed the same attorney to represent the defendants who represented them at the first trial and refused to permit him to decline the appointment. Manifestly, there was no basis for the claim of lack of time to prepare for the second trial. Moreover, the ability of counsel to arrange for his fees could not have been serious. Touhy was the owner of considerable property, including a large and valuable estate in Cook county. There was $2700 in custody of Federal officers which had not been identified as the proceeds of any crime, and this had been assigned to counsel by the defendants. Courts cannot be obliged to wait upon the payment of fees to counsel before bringing an accused to trial, otherwise *Page 348 many miscarriages of justice would result. The defendants were in nowise prejudiced by denying the continuance.

It is claimed that Costner's testimony as to the payment of $2400 and the conversation about it with Banghart after Factor's release was incompetent, because a conversation out of the presence of the accused, after the termination of a conspiracy, is not admissible. The same claim is made as to the evidence of the police trap at Willow Springs, and it is pointed out that the defendants were then in custody on another charge. The evidence shows that the conspiracy had not terminated. It was a part of the agreement for release that $70,000 should be paid down and $50,000 more should be paid a week or ten days later. All the conspirators are deemed in law to be parties to all acts done by any of the other conspirators in furtherance of the common design. (People v. Cohn, 358 Ill. 326; People v. Walinsky, 300 id. 92.) The testimony was properly admitted.

Complaint is made by counsel for the defendants because he was not permitted to interrogate Costner in private prior to his going on the witness stand. Costner was brought from Baltimore to Chicago on February 17 and was called as a witness on the following Monday. Counsel suggested to the court that the name of the witness did not appear in the list given him by the State. The assistant State's attorney explained that when the case was called for trial Costner's whereabouts was unknown and the State was not then in possession of any definite information as to his connection with the case. Thereupon counsel for the defendants moved to withdraw a juror, and the motion was denied. Leave was asked for the defendants' counsel to examine the witness in private. The court offered to permit an examination provided it should be conducted in the presence of the assistant State's attorney or Capt. Gilbert. At the end of a colloquy over the matter counsel interrogated the witness in the outer chamber of the court *Page 349 in the presence of Capt. Gilbert. No prejudice to the defendants appears to have resulted in the action of the court. In fact, we know of no rule which would authorize the court to compel a witness to be examined in private by counsel for either side of a case, especially in the absence of the consent of the witness, and it is not intimated that Costner was either desirous or willing to be interrogated out of the presence of the court. There was no error in permitting the witness to testify. People v. Scott, 261 Ill. 165.

Clara Sczech was called by the court at the request of the People and testified that she was employed at the Glenview house by Henrichsen to cook one meal a day and strighten up after supper. Andy McFadden, Sharkey and Tribbles lived there. Kator, Eddie McFadden and Banghart frequented the place. She admitted making a sworn statement on October 26, 1933, that she had seen Touhy, Connors and Schafer there, but testified she was so nervous she did not know what to do and made mistakes in her statement. She said she never saw Costner around the place, and that she never saw Factor or anybody else in custody there and had never heard Factor discussed. It is urged that the court erred in calling her as a court witness. The State's attorney informed the court that prior to the first trial she had made a sworn statement in which she identified pictures of Touhy, Connors, Banghart and Schafer; that she stated she had seen them at the Glenview house; that on the first trial she contradicted that statement and denied she had ever seen Touhy, Schafer or Connors there; that she would persist in her denial and that the State could not vouch for her veracity. InCarle v. People, 200 Ill. 494, we approved the calling of an eyewitness to a crime for whose veracity the State's attorney could not vouch. Subsequently, in People v. Cleminson, 250 Ill. 135, a witness called by the court who knew nothing about the crime was subjected to a searching and scurrilous cross-examination on collateral matters. We said in that *Page 350 case that the practice of the court calling a witness at the request of either party should not be extended beyond the limits of the rule announced in the Carle case, but we have never held that the power of a trial court to call a witness is limited to the calling of an eye-witness. We have held the rule to be that a witness should not be called except where it is shown that otherwise there may be a miscarriage of justice. Where the State's attorney for some reason, of which he informs the court, doubts the integrity or veracity of a witness he is not obliged to call him, but the court may call the witness and allow him to be cross-examined by either side. The practice should not be extended further than this, and the cross-examination should be limited to the issues. (People v.Daniels, 354 Ill. 600; People v. Rotello, 339 id. 448;People v. Johnson, 333 id. 469.) Clara Sczech was employed at a rendezvous of the defendants, rented at Touhy's direction. She was connected with the house and with the defendants. The court was advised of sufficient reasons why the State's attorney could not vouch for her credibility. There was no error in calling her as a court witness.

It is complained that the defendants were not allowed to develop evidence relating to the previous kidnapping of Factor's son, his release without ransom, and the details of a gang war between the Al Capone gang and the Touhy gang concerning the illegal distribution of beer. It is urged that such evidence would tend to show that Factor was kidnapped by the syndicate or that the charge was falsely made in order to escape extradition. In connection with the gang war it is claimed that one of the People's witnesses identified a guard at the Dells as one of the kidnappers and that the Dells was operated by the Capone gang. The witness did not identify one of the kidnappers as a guard. He testified that he saw the man leaning against a car in the Dells yard and "concluded" he was a guard. There is no other testimony even tending to show *Page 351 that the man was a guard at the resort. The evidence shows that Silvers, the man who twice came out and communicated with the kidnappers just prior to the capture, was in conference with Touhy and his associates on two days shortly afterward. Even though Factor's son was released without ransom from an earlier kidnapping through the efforts of members of the Capone gang, and even though there was a gang war over illegal beer territory, those facts would not tend to throw any light on the issues. It would rather tend to becloud them. The court did not unduly limit the testimony in the respects complained of.

The instruction given by the court concerning the penalty for kidnapping is not subject to the criticism pointed out inPeople v. Rongetti, 331 Ill. 581. There the defendant was charged with abortion, and the instruction covered not only that crime but the crime of attempted abortion as well. The instruction here complained of does not cover two separate offenses. It merely defines the elements of the crime, and the jury could not have been misled by it.

The following instruction was given:

"The defendants under the law are presumed to be innocent of the charge in the indictment and this presumption remains throughout the trial with the defendants until you have been satisfied by the evidence in the case beyond all reasonable doubt of the guilt of the defendants. * * * Throughout this case the burden of proving the guilt of the defendants beyond all reasonable doubt is on the State and the law does not require the defendants to prove their innocence."

It is objected that the instruction intimates the presumption need not prevail during the whole trial but only "until something happens." The instruction is unlike the instruction condemned in People v. Ambach, 247 Ill. 451, and the objection is unfounded. An instruction of similar import but in different language was approved in the Rongetti case, supra. Instructions are given after the hearing of all the *Page 352 evidence and the arguments of counsel, and we are unable to see wherein the jury could have considered this instruction other than in connection with the whole case.

The court instructed the jury as to the meaning of reasonable doubt. We have often criticised the giving of a similar instruction because the term needs no definition but thus far we have never held the giving of such an instruction to be reversible error.

An instruction advised the jury that they are the sole judges of the credibility of the witnesses and enumerated the general tests to be considered. It is objected that a different test is to be applied to accomplices, and that it was not within the province of the court to single out and indicate that a witness may be corroborated or contradicted. This instruction is not subject to either criticism. The tests enumerated were applicable to the testimony of accomplices as well as other witnesses.

The next instruction dealt only with accomplices. It is:

"Walter Henrichsen, Isaac Costner and Basil Banghart are persons defined by law to be accomplices to the crime charged in this indictment. The testimony of an accomplice is competent evidence but such testimony is liable to grave suspicion and should be acted upon with great caution. If the testimony of an accomplice carries conviction and the jury are convinced of its truth beyond a reasonable doubt they should give it the same weight as would be given to the testimony of a witness who is in no respect implicated in the offense and the credibility ofsuch an accomplice is for the jury to pass upon as they passupon the credibility of any other witness."

The only objection made at the trial to this instruction by counsel for the defendants was, "that Basil Banghart does not come in the class of accomplice, not having been called by the State but having been called by defendants." It is argued that there should be a different rule applicable to Henrichsen and Costner, who took the stand for the *Page 353 People and confessed their guilt, than that applicable to Banghart, who testified for the defendants and denied his guilt. Although the term "accomplice" is generally applied to those testifying against their fellow-criminals, (Cross v. People, 47 Ill. 152,) an accomplice is one who is in some way concerned in or associated with another in the commission of a crime. (Bouvier's Law Dict.; People v. Turner,260 Ill. 84; Cross v. People, supra.) No reason is advanced, and none is apparent, why one who is in fact an accomplice should not have his testimony scrutinized carefully before it is relied on, no matter on which side of the case he testified.

It is urged that the portion of the above instruction which we have italicized renders it reversible error under the holding in People v. Rongetti, 338 Ill. 56. In that case the instruction was held to be erroneous because it charged the jury to pass upon the credibility of an accomplice in the same way as they pass upon the credibility of any other witness. The accomplice testified for the State, and the defendant had a right to have the jury instructed that his testimony should be put to a severer test than that which is applied to ordinary witnesses. The defendant was prejudiced by the omission to so instruct the jury, but in this case, Banghart, who is the only witness referred to in the objection, was a witness for the defendants, and if the jury were not required to apply strict scrutiny to his testimony the result would favor the defendants and they cannot complain of the error. Counsel for the defendants urge other objections to the instruction, but they were not included in the specific objection made in the trial court and they will not be further considered.

Some of the evidence was circumstantial, and the court did not err in giving an instruction defining it. Nor was there any error in giving the instruction defining accessories. Some of the defendants who were not placed at the scene of the actual kidnapping by the People's witnesses *Page 354 were connected by the testimony with other phases of it, bringing them within the terms of the definition.

The jury were instructed that if they believed from the evidence, beyond all reasonable doubt, that any defendant in this case collected or attempted to collect ransom or money from John Factor knowing him to have been so seized or secreted for the purpose of collecting ransom, such defendant is guilty of kidnapping for ransom. The objection raised to the instruction in the trial court is, that it would include an accessory after the fact and is misleading. It is urged that under its language it is possible to connect the attempt to collect money at Willow Springs with the original crime. If the testimony is to be credited, that incident was a part of the crime and those engaged in it were participants in the whole program. The instruction might well have been couched in better language, but it was not misleading and there was no reversible error in giving it.

In addition to adopting five suggestions offered by the defendants the court refused thirty-two others offered by them. Fourteen of the offered suggestions were on the question of the credibility of the witnesses and the weight to be accorded the testimony of accomplices. One was on the failure of the defendants to testify. Others were on reasonable doubt. Each of these subjects and other suggestions offered were covered by other given instructions. We have often condemned the practice of giving numerous instructions upon the same subject. There was no error in refusing the suggestions.

An alibi suggestion offered by the defendants told the jury that "if in view of all the evidence, the jury have a reasonable doubt as to whether either of the defendants was present but was in some other place when the crime was committed, they should give such defendant or defendants the benefit of the doubt and find them not guilty." It was not necessary for a defendant to be actually present at the *Page 355 kidnapping if he was otherwise a party to the crime. The suggestion was correctly refused.

After a careful consideration we are of the opinion there was no reversible error in the giving or refusal of instructions.

In support of the contention that the evidence is not sufficient to show the defendants' guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, the sufficiency of the identifications and the testimony of the accomplice witnesses are particularly attacked. Several matters alleged to be discrepancies are urged. It is always to be expected that in a case where the evidence is as voluminous as this there will be some conflict in the testimony. The identifications are not disputed. The jury saw and heard all the witnesses, including the accomplices. The weight of the testimony was for the jury to determine. The evidence so overwhelmingly establishes the guilt of the defendants that the jury could not reasonably have arrived at any other verdict.

We have examined in detail the many objections and criticisms urged upon us and find no reversible error. The question upon review is not whether the record is perfect but whether the defendant has had a fair trial under the law and whether his conviction is based on evidence establishing his guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Where the error complained of could not reasonably have affected the result the judgment will be affirmed. People v. Cardinelli, 297 Ill. 116; People v.Haensel, 293 id. 33.

The effort to show partisanship and bias on the part of the trial judge is wholly unjustified. His rulings, in the main, were correct and we find no prejudicial error in any of them. The defendants were accorded a fair trial, and the jury were justified from the evidence in finding them guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

The judgment of the criminal court is affirmed.

Roger Touhy (September 18, 1898 – December 16, 1959) was an Irish-American mob boss and prohibition-era bootlegger from Chicago, Illinois. He is best remembered for having been framed for the 1933 faked kidnapping of gangster John "Jake the Barber" Factor, a brother of cosmetics manufacturer Max Factor Sr. Despite numerous appeals and at least one court ruling freeing him, Touhy spent 26 years in prison. Touhy was released in November 1959. He was murdered by the Chicago Outfit less than a month later.Contents1 Early years2 Criminal involvement3 Rivalry with Capone4 Framed for Factor kidnapping4.1 Appeals4.2 Release5 Death6 References7 Further reading8 External linksEarly yearsRoger Touhy was born in September 1898 in Chicago to Irish immigrant parents. His father, James A. Touhy, was a policeman on Chicago's Near West Side. James Touhy and his wife Mary were the parents of six sons and two daughters.[2] When Roger was a small child, however, his mother died in a house fire.

Roger Touhy grew up to be 5'6" tall, with curly hair and a beak nose. He was highly intelligent. Unfortunately, James Touhy could not properly raise his sons by himself, and five of them eventually turned to crime. James Touhy Jr. was shot and killed by a policeman during an attempted robbery in 1917. John Touhy was killed ten years later by gunmen belonging to gangster Al Capone's Chicago Outfit. Joseph Touhy was shot dead by Capone gunmen in 1929. Tommy "The Terrible" Touhy became a major organized crime figure in Chicago and was named "Public Enemy Number One" in 1934. Only Edward Touhy managed to stay out of trouble by becoming a bartender.[3][4]

The youngest of James Touhy's sons, Roger Touhy tried to remain on the right side of the law. He dropped out of school after the eighth grade, not unusual for the time, and worked at various jobs including as a telegrapher, an oil field worker, and a union organizer. He served in the U.S. Navy during World War I.[3][4]

Discharged from the Navy at the war's end, Touhy married Clara Morgan in Chicago in 1923. Determined to remain honest, he became first a cab driver, then an automobile salesman. His auto sales career was successful, and he made enough money to form a trucking company in Des Plaines with his brothers Tommy and Eddie.[5]

Criminal involvementWith the onset of Prohibition, Touhy and his brothers began distributing illegal beer and liquor in the northwest suburbs of Chicago. Touhy entered into a partnership with Matt Kolb, who was already supplying the Chicago Outfit with a third of its beer, as well as running highly profitable gambling and loan sharking operations north of Chicago. The two men established a brewery and cooperage, and produced a high quality beer. They soon were selling 1,000 barrels a week at $55 a barrel (for a profit of 92 percent).[4][6]

In 1926, Touhy expanded into illegal gambling and installed slot machines in saloons throughout the northwest Chicago suburbs. By 1926, his slot machine operations alone grossed over $1 million a year ($14 million in 2019 dollars).[7][8]

Rivalry with CaponeBy 1929, Al Capone was ordering hundreds of barrels of beer a week from Roger Touhy. Envious of the stranglehold Touhy had on the northwest suburbs and unwilling to pay Touhy the high per-barrel cost of his quality beer, Capone wanted to take over Touhy's organization. That year, he sent Jack "Machine Gun" McGurn and Louis "Little New York" Campagna to Touhy's headquarters in Schiller Park. Touhy refused to be intimidated.[4][7]

In 1931, Capone sent two more of his men, Frank Rio and Willie Heeney, to demand that Touhy once again hand over control of his operations. Touhy himself had no armed men among his gang members. Realizing that Capone would try to use force after his refusal, Touhy approached local law enforcement officers and others to ask for their support. He explained that he simply wanted to sell beer, while domination by the Capone gang would bring lawlessness, gambling and prostitution. Local leaders agreed to help him. Merchants refused to use Capone's gambling punchboards or buy his own low-quality beer. When Rio and Heeney met with Touhy, off-duty police and local farmers were lounging about in the building. This show of force unnerved Capone's gunmen, who reported that Touhy's gang must have had hundreds of armed men.[4][7][9]

Capone continued to send men to talk to Touhy, but he also began to test Touhy's strength. Sporadic gun battles between Touhy's and Capone's men took place in rural Cook County over the next few years. When Touhy won the support of Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak, the increasingly frequent attempted hits began happening inside the city limits as well.[4] It was during this time that Touhy gained his unlikely nickname, "Touhy the Terrible".[9]

In October 1931, Capone ordered Matt Kolb killed.[6][10][11] After that, open war broke out between the now-armed Touhy Gang and the Chicago Outfit.

On May 5, 1932, Touhy and three others held nearly a hundred people hostage at Teamsters headquarters in Chicago. Several Chicago-area union leaders had paid Touhy $75,000 in cash to help them rid their unions of the Capone mob's influence. After three hours, Touhy and his gunmen left— taking with them two union leaders who were part of Capone's operation. The men were released unharmed two days later, but a mob war between Touhy and Capone's associate Murray "The Camel" Humphreys also began.[6]

In 1933, Capone had corrupt law enforcement officers arrest Touhy for the kidnapping of William A. Hamm, the brewery heir. In fact, the kidnapping had actually been committed by the Barker brothers, working with gangster Alvin Karpis. The FBI already had substantial evidence that the Barker-Karpis gang had kidnapped Hamm (who was freed unharmed four days later after payment of a $100,000 ransom), and nothing but hearsay linked Touhy to the crime. Nevertheless, Touhy and three others were indicted on kidnapping charges on August 12, 1933. They were found not guilty on November 28.[6][9][12][13][14]

Framed for Factor kidnappingWhile awaiting release after the Hamm kidnapping trial, Touhy was arrested again on December 4, 1933 — this time for the kidnapping of John "Jake the Barber" Factor, brother of cosmetics mogul Max Factor Sr.[15]

The Factor kidnapping was a frame-up. Factor and Al Capone had arranged to fake the kidnapping and produce evidence implicating Touhy in order to eliminate him, so as to assume control over his organization. The plan was risky: Factor himself was a known mobster, and was on the run from British authorities who were seeking him on mail fraud charges. Capone had also already contrived to have Touhy indicted on the Hamm kidnapping, and Touhy was under close police watch at the time of the Factor kidnapping. Nevertheless, on June 30, 1933, Factor was abducted by four men on a Chicago street corner. Factor later claimed at trial that he was tortured during his imprisonment, and that the kidnappers took pictures of themselves which showed him in their clutches. Factor's wife paid a $75,000 ransom, and Factor was freed on July 12.[4][6][12][13] During Touhy's trial for the kidnapping of William Hamm, Touhy was put in a secret police lineup and positively identified as one of the kidnappers by Factor.[16]

Roger Touhy and three of his top aides went on trial for the John Factor kidnapping on January 15, 1934. Several eyewitnesses proved remarkably unreliable during the trial, and later evidence showed that many prosecution witnesses perjured themselves in the attempt to convict Touhy. At least one juror refused to report for duty midway through the trial, while another juror admitted he had perjured himself during voir dire. A mistrial was declared on February 2.[4][6][12][13][17]

A second trial began on February 13, 1934. Once more, witnesses for the prosecution perjured themselves on a massive scale. Despite unreliable testimony from Factor himself, the jury convicted Touhy and his three associates on February 22. Touhy was sentenced to 99 years in prison. He was incarcerated at Stateville Correctional immediately filed an appeal. Over the next eight years, he spent most of his bootlegger's fortune on legal fees.[6][13]

On October 9, 1942, Touhy and six other men escaped from Stateville prison. After a month, Touhy and the others were discovered living in a Chicago boarding house. Touhy and three others surrendered peacefully. The remaining two escapees tried to fight their way out and were killed. Touhy re-entered Stateville on December 31, 1942, and was sentenced to an additional 199 years in prison for the escape.[6][9][13]

In 1944, 20th Century Fox released a semi-biographical and highly fictionalized film based on Touhy's life, title Roger Touhy, Gangster.[19] Touhy successfully sued the studio for defamation of character (after six years, he won a judgment of $15,000), but Fox was able to distribute the film overseas without legal repercussions.[20]

On August 9, 1954, a federal district court ruled that Touhy should be freed. The court found that Factor's kidnapping had been a hoax and Touhy's conviction secured with perjured testimony; moreover, the court ruled that both the state's lead investigator (an active-duty Chicago police captain) and the state's attorney both knew of the perjured evidence but kept these facts from the defense. Touhy was freed; however, less than 50 hours later, he was back in prison. A federal court of appeals ruled that the district court lacked jurisdiction to hear the case because Touhy had not yet exhausted all state court appeals. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the appellate court's ruling in February 1955.[13][21]

On July 31, 1957, Republican Governor William Stratton commuted Touhy's original 99-year sentence to 72 years, and reduced his 199-year sentence for escaping to three years. Touhy subsequently won parole for the kidnapping. Under the terms of the parole, he had to serve six more months for the kidnapping and the full three-year sentence for the escape. Under these terms, which he accepted, Touhy would have been eligible for release in April 1961.[13][22][23]

Touhy's autobiography, The Stolen Years, was published in the fall of 1959.[4][6] John Factor sued Touhy for libel for the statements published in the book.[24]

ReleaseOn November 13, 1959, Touhy was granted parole for his escape. He left Stateville on November 24, 1959 – 25 years and nine months to the day after his incarceration.[4][6][13][25] Two days later, a federal judge refused to throw out his 1933 conviction despite convincing evidence of prosecutorial misconduct and perjury.[26]

DeathOn December 16, 1959, 22 days after Roger Touhy was released from prison, he and his bodyguard were gunned down by mob hit men. Touhy and his bodyguard were entering the home of Touhy's sister at about 10:30 p.m. Touhy and Walter Miller, a retired Chicago police detective, were climbing the steps to the home when two men appeared from the shadows behind them. Touhy and Miller turned, and Miller showed them his police badge and told the men he was a police officer. The two men then pulled shotguns from beneath their overcoats, and fired five shots. Touhy was struck twice, once in each leg above the knee. Miller was struck three times, but managed to draw his revolver and fire three shots at the departing gunmen. While being rushed to a hospital, Touhy told a newsman, "I've been expecting it. The bastards never forget!"[27] Miller was taken to Loretto Hospital, where he eventually recovered. Touhy was taken to St. Anne's Hospital, where he lived for an hour before dying of shock and loss of blood.[3][4][6][28]

Roger Touhy's killers were never identified. One historian has suggested that Murray "The Camel" Humphreys was behind the assassination, having never forgiven Touhy for humiliating him in 1931 or for comments made about him in Touhy's recently released autobiography.[9]

Others believe the killers to have been Sam "Momo" Giancana, Marshall Caifano or Samuel "Teets" Bataglia, all former members of the 42 Gang which had fought Touhy on the back roads of northwestern Cook County in 1931-1933.[citation needed]A gangster is a criminal who is a member of a gang. Some gangs are considered to be part of organized crime. Gangsters are also called mobsters, a term derived from mob and the suffix -ster.[1] Gangs provide a level of organization and resources that support much larger and more complex criminal transactions than an individual criminal could achieve. Gangsters have been active for many years in countries around the world. Gangsters are the subject of many novels, films, and video games.Contents1 Etymology2 Gangs3 Regional variants3.1 Europe3.2 Asia3.3 United States and Canada3.4 Latin America4 Notorious individuals4.1 Johnny Torrio4.2 Lucky Luciano4.3 Al Capone4.4 Frank Costello4.5 Carlo Gambino5 In popular culture5.1 United States5.2 Latin America5.3 East Asia6 See also7 Citations8 References8.1 In the United States8.2 In popular culture9 External linksEtymologySome contemporary criminals refer to themselves as "gangsta" in reference to non-rhotic black American pronunciation.

Gangs

Yakuza, or Japanese mafia are not allowed to show their tattoos in public except during the Sanja Matsuri festival.In today's usage, the term "gang" is generally used for a criminal organization, and the term "gangster" invariably describes a criminal.[2] Much has been written on the subject of gangs, although there is no clear consensus about what constitutes a gang or what situations lead to gang formation and evolution. There is agreement that the members of a gang have a sense of common identity and belonging, and this is typically reinforced through shared activities and through visual identifications such as special clothing, tattoos or rings.[3] Some preconceptions may be false. For example, the common view that illegal drug distribution in the United States is largely controlled by gangs has been questioned.[4]

A gang may be a relatively small group of people who cooperate in criminal acts, as with the Jesse James gang, which ended with the leader's death in 1882. But a gang may be a larger group with a formal organization that survives the death of its leader. The Chicago Outfit created by Johnny Torrio and Al Capone outlasted its founders and survived into the 21st century. Large and well structured gangs such as the Mafia, drug cartels, Triads or even outlaw motorcycle gangs can undertake complex transactions that would be far beyond the capability of one individual, and can provide services such as dispute arbitration and contract enforcement that parallel those of a legitimate government.[5]

The term "organized crime" is associated with gangs and gangsters, but is not synonymous. A small street gang that engages in sporadic low-level crime would not be seen as "organized". An organization that coordinates gangs in different countries involved in the international trade in drugs or prostitutes may not be considered a "gang".[6]

Although gangs and gangsters have existed in many countries and at many times in the past, they have played more prominent roles during times of weakened social order or when governments have attempted to suppress access to goods or services for which there is a high demand.[citation needed]

Regional variantsEurope

Sketch of the 1901 maxi trial of suspected mafiosi in Palermo. From the newspaper L'Ora, May 1901The Sicilian Mafia, or Cosa Nostra is a criminal syndicate that emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in Sicily, Italy. It is a loose association of criminal groups that share common organizational structure and code of conduct. The origins lie in the upheaval of Sicily's transition out of feudalism in 1812 and its later annexation by mainland Italy in 1860. Under feudalism, the nobility owned most of the land and enforced law and order through their private armies. After 1812, the feudal barons steadily sold off or rented their lands to private citizens. Primogeniture was abolished, land could no longer be seized to settle debts, and one fifth of the land was to become private property of the peasants.[7]

Organized crime has existed in Russia since the days of Imperial Russia in the form of banditry and thievery. In the Soviet period Vory v Zakone emerged, a class of criminals that had to aoffere by certain rules in the prison system. One such rule was that cooperation with the authorities of any kind was forofferden. During World War II some prisoners made a deal with the government to join the armed forces in return for a reduced sentence, but upon their return to prison they were attacked and killed by inmates who remained loyal to the rules of the thieves.[8] In 1988 the Soviet Union legalized private enterprise but did not provide regulations to ensure the security of market economy. Crude markets emerged, the most notorious being the Rizhsky market where prostitution rings were run next to the Rizhsky Railway Station in Moscow.[9]

As the Soviet Union headed for collapse many former government workers turned to crime, while others moved overseas. Former KGB agents and veterans of the Afghan and First and Second Chechen Wars, now unemployed but with experience that could prove useful in crime, joined the increasing crime wave.[9] At first, the Vory v Zakone played a key role in arbitrating the gang wars that erupted in the 1990s.[10] By the mid-1990s it was believed that "Don" Semion Mogilevich had become the "boss of all bosses" of most Russian Mafia syndicates in the world, described by the British government as "one of the most dangerous men in the world".[11] More recently, criminals with stronger ties to big business and the government have displaced the Vory from some of their traditional niches, although the Vory are still strong in gambling and the retail trade.[10]

The Albanian Mafia is active in Albania, the United States, and the European Union (EU) countries, participating in a diverse range of criminal enterprises including drug and arms trafficking.[12][13] The people of the mountainous country of Albania have always had strong traditions of family and clan loyalty, in some ways similar to that of southern Italy. Ethnic Albanian gangs have grown rapidly since 1992 during the prolonged period of instability in the Balkans after the collapse of Yugoslavia. This coincided with large scale migration throughout Europe and to the United States and Canada. Although based in Albania, the gangs often handle international transactions such as trafficking in economic migrants, drugs and other contraband, and weapons.[14] Other criminal organizations that emerged in the Balkans around this time are popularly called the Serbian Mafia, Bosnian Mafia, Bulgarian Mafia and so on.

Asia

Du Yuesheng (1888–1951), a Chinese gangster and important Kuomintang supporter who spent much of his life in ShanghaiIn China, Triads trace their roots to resistance or rebel groups opposed to Manchu rule during the Qing dynasty, which were given the triangle as their emblem.[15] The first record of a triad society, Heaven and Earth Gathering, dates to the Lin Shuangwen uprising on Taiwan from 1786 to 1787.[16] The triads evolved into criminal societies. When the Chinese Communist Party came to power in 1949 in mainland China, law enforcement became stricter and tough governmental crackdown on criminal organizations forced the triads to migrate to Hong Kong, then a British colony, and other cities around the world. Triads today are highly organized, with departments responsible for functions such as accounting, recruiting, communications, training and welfare in addition to the operational arms. They engage in a variety of crimes including extortion, money laundering, smuggling, trafficking and prostitution.[17]

Yakuza are members of traditional organized crime syndicates in Japan. They are notorious for their strict codes of conduct and very organized nature. As of 2009 they had an estimated 80,900 members.[18] Most modern yakuza derive from two classifications which emerged in the mid-Edo period: tekiya, those who primarily peddled illicit, stolen or shoddy goods; and bakuto, those who were involved in or participated in gambling.[19]

United States and CanadaAs American society and culture developed, new immigrants were relocating to the United States. The first major gangs in 19th century New York City were the Irish gangs such as the Whyos and the Dead Rabbits.[20] These were followed by the Italian Five Points Gang and later a Jewish gang known as the Eastman Gang.[21][22] There were also "Nativist" anti-immigration gangs such as the Bowery Boys. The American Mafia arose from offshoots of the Mafia that emerged in the United States during the late nineteenth century, following waves of emigration from Sicily. There were similar offshoots in Canada among Italian Canadians.[citation needed]

In the later 1860s many Chinese emigrated to the United States, escaping from insecurity and economic hardship at home, at first working on the west coast and later moving east. The new immigrants formed Chinese Benevolent Associations. In some cases these evolved into Tongs, or criminal organizations primarily involved in gambling. Members of Triads who migrated to the United States often joined these tongs. With a new wave of migration in the 1960s, street gangs began to flourish in major cities. The tongs recruited these gangs to protect their extortion, gambling and narcotics operations.[23]

The terms "gangster" and "mobster" are mostly used in the United States to refer to members of criminal organizations associated with Prohibition or with an American offshoot of the Italian Mafia (such as the Chicago Outfit, the Philadelphia Mafia, or the Five Families).[citation needed] In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution banned the sale, manufacture, and transportation of alcohol for consumption. Many gangs sold alcohol illegally for tremendous profit, and used acute violence to stake turf and protect their interest. Often, police officers and politicians were paid off or extorted to ensure continued operation.[24]

Latin America

Members of Colonel Martinez's Search Bloc celebrate over Pablo Escobar's body on December 2, 1993Most cocaine is grown and processed in South America, particularly in Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, and smuggled into the United States and Europe, the United States being the world's largest consumer of cocaine.[25] Colombia is the world's leading producer of cocaine, and also produces heroin that is mostly destined for the US market.[26] The Medellín Cartel was an organized network of drug suppliers and smugglers originating in the city of Medellín, Colombia. The gang operated in Colombia, Bolivia, Peru, Central America, the United States, as well as Canada and Europe throughout the 1970s and 1980s. It was founded and run by Ochoa Vázquez brothers with Pablo Escobar. By 1993, the Colombian government, helped by the US, had successfully dismantled the cartel by imprisoning or hunting and gunning down its members.[27]

Although Mexican drug cartels, or drug trafficking organizations, have existed for several decades, they have become more powerful since the demise of Colombia's Cali and Medellín cartels in the 1990s. Mexican drug cartels now dominate the wholesale illicit drug market in the United States.[28] Sixty five percent of cocaine enters the United States through Mexico, and the vast majority of the rest enters through Florida. Cocaine shipments from South America transported through Mexico or Central America are generally moved over land or by air to staging sites in northern Mexico. The cocaine is then broken down into smaller loads for smuggling across the U.S.–Mexico border.[29] Arrests of key gang leaders, particularly in the Tijuana and Gulf cartels, have led to increasing drug violence as gangs fight for control of the trafficking routes into the United States.[30]

Cocaine traffickers from Colombia, and recently Mexico, have also established a labyrinth of smuggling routes throughout the Caribbean, the Bahama Island chain, and South Florida. They often hire traffickers from Mexico or the Dominican Republic to transport the drug. The traffickers use a variety of smuggling techniques to transfer their drug to U.S. markets. These include airdrops of 500–700 kg in the Bahama Islands or off the coast of Puerto Rico, mid-ocean boat-to-boat transfers of 500–2,000 kg, and the commercial shipment of tonnes of cocaine through the port of Miami. Another route of cocaine traffic goes through Chile, this route is primarily used for cocaine produced in Bolivia since the nearest seaports lie in northern Chile. The arid Bolivia-Chile border is easily crossed by 4x4 vehicles that then head to the seaports of Iquique and Antofagasta.[citation needed]

Notorious individualsJohnny TorrioMain article: Johnny Torrio

Mugshot of Johnny Torrio in 1936Born in southern Italy in 1882, Torrio immigrated to the United States with his mother after his father's death, which happened when he was three years old. Known as "The Fox" for his cunning, he helped the formation of the Chicago Outfit and he is credited for inspiring the birth of the National Crime Syndicate.[31] He was a big influence on Al Capone, who regarded him as a mentor.[32] After the assassination of Big Jim Colosimo, Torrio took his place in the Chicago Outfit. He was severely wounded by members of the North Side Gang while returning from a shopping trip, forcing him, along with other problems, to quit the criminal activity. He died in 1957 and the media learned about his death three weeks after his burial.[33] Elmer Irey, official of the United States Treasury Department, defined Torrio "the biggest gangster in America", "the smartest and the best of all the hoodlums"[34] while Virgil W. Peterson of the Chicago Crime Commission considered him "an organizational genius".[35]

Lucky LucianoMain article: Lucky LucianoCharles Lucky Luciano born Salvatore Lucania[36] [salvaˈtoːre lukaˈniːa];[37] November 24, 1897 – January 26, 1962) was probably the most influential Mafia boss, he was an Italian-born mobster, criminal mastermind, and crime boss who operated mainly in the United States. Along with his associates, he was instrumental in the development of the National Crime Syndicate. Luciano is the father of modern organized crime in the United States for the establishment of The Commission in 1931. His crime family was later renamed the Genovese crime family.[38]

Al CaponeMain article: Al Capone

Mug shot of Al Capone. Although never convicted of racketeering, Capone was a protégé and successor of Torrio, later convicted of income tax evasion by the federal government.Al Capone was one of the most famous gangsters during the roaring twenties. Born in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in 1899 to immigrant parents, Capone was recruited by members of the Five Points Gang in the early 1920s. Capone's childhood friend, Lucky Luciano, was also originally a member of the Five Points Gang. Capone would rise to control a major portion of illicit activity such as gambling, prostitution, and bootlegging in Chicago during the early twentieth century.[39]

Frank Costello

American gangster Frank Costello, testifying before the Kefauver Committee, during an investigation of organized crime.Main article: Frank CostelloFrank Costello was an influential gangster. He was born in southern Italy but moved to America when he was four years old. He later changed his name from Francesco Castiglia to Frank Costello when he joined a gang at age 13. His name change led some people to mistakenly believe he was Irish. He worked for Charlie Luciano and was in charge of bootlegging and gambling. He was also the Luciano gangs emissary to politicians, he later held sway over politicians which enabled him political protection to continue his business. He took charge of Lucianos gang when Lucky Luciano was arrested, during his time in power he expanded the gang's operations into white collar crimes. He decided to step down from power when Vito Genovese returned from Italy and challenged him for power to run the Luciano crime family. Costello retired from the gangster life style and died peacefully in 1973.

Carlo GambinoMain article: Carlo GambinoCarlo Gambino was an influential gangster in America. From 1961 until he died in 1976, he was known for being very low key. Gambino was born in Palermo, Sicily, but moved to the United States at the age of 21. Through his relatives the Castellano, he joined the Masseria Family while Lucky Luciano was the underboss in the Masseria Family, Gambino worked for him. After Luciano had Masseria killed, Luciano became the boss, and Gambino was sent by Luciano to the Scalise Family. Later Scalise was stripped of his rank, and Vincenzo Mangano became boss until 1951, when Mangano disappeared. His body was never found. Gambino then worked his way up the ladder to be the last known boss to have full control of the commission besides Luciano. Gambino was known to have taken the Mafia out of the lime light and kept it in the dark and away from the media. [40]

In popular cultureFurther information: Gangster filmGangs have long been the subject of movies. In fact, the first feature-length movie ever produced was The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906), an Australian production that traced the life of the outlaw Ned Kelly (1855–1880).[41] The United States has profoundly influenced the genre, but other cultures have contributed distinctive and often excellent gangster movies.[citation needed]

United StatesThe classic gangster movie ranks with the Western as one of the most successful creations of the American movie industry. The "classic" form of gangster movie, rarely produced in recent years, tells of a gangster working his way up through his enterprise and daring, until his organization collapses while he is at the peak of his powers. Although the ending is presented as a moral outcome, it is usually seen as no more than an accidental failure. The gangster is typically articulate, although at times lonely and depressed, and his worldly wisdom and defiance of social norms has a strong appeal, particularly to adolescents.[42]Publicity still of Romanian-born Edward G. Robinson, who starred in several American gangster moviesThe stereotypical image and myth of the American gangster is closely associated with organized crime during the Prohibition era of the 1920s and 1930s.[43]

The years 1931 and 1932 saw the genre produce three classics: Warner Bros.' Little Caesar and The Public Enemy, which made screen icons out of Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney, and Howard Hughes' Scarface starring Paul Muni, which offered a dark psychological analysis of a fictionalized Al Capone.[44] These films chronicle the quick rise, and equally quick downfall, of three young, violent criminals, and represent the genre in its purest form before moral pressure would force it to change and evolve. Though the gangster in each film would face a violent downfall which was designed to remind the viewers of the consequences of crime, audiences were often able to identify with the charismatic anti-hero. Those suffering from the Depression were able to relate to the gangster character who worked hard to earn his place and success in the world, only to have it all taken away from him.[45]

Latin AmericaLatin American gangster movies are known for their gritty realism. Soy un delincuente (English: I Am a Criminal) is a 1976 Venezuelan film by director Clemente de la Cerda. The film tells the story of Ramón Antonio Brizuela, a real-life individual, who since childhood has to deal with rampant violence and the drugs, sex and petty thievery of a Caracas slum. Starting with delinquency, Ramón moves on to serious gang activity and robberies. He grows into a tough, self-confident young man who is hardened to violence. His views change when his fiancée's brother is killed in a robbery. The film was a blockbuster hit in Venezuela.[46]

City of God (Portuguese: Cidade de Deus) is a 2002 Brazilian crime drama film directed by Fernando Meirelles and co-directed by Kátia Lund, released in its home country in 2002 and worldwide in 2003. All the characters existed in reality, and the story is based on real events. It depicts the growth of organized crime in the Cidade de Deus suburb of Rio de Janeiro, between the end of the '60s and the beginning of the '80s, with the closure of the film depicting the war between the drug dealer Li'l Zé and criminal Knockout Ned.[47] The film received four Academy Award nominations in 2004.[48]

East AsiaThe first yakuza (gangster) film made in Japan was Bakuto (Gambler, 1964). The genre soon became popular, and by the 1970s the Japanese film industry was turning out a hundred mostly low-budget yakuza films each year. The films are descendants of the samurai epics, and are closer to Westerns than to Hollywood gangster movies. The hero is typically torn between compassion for the oppressed and his sense of duty to the gang. The plots are generally highly stylized, starting with the protagonist being released from prison and ending in a gory sword fight in which he dies an honorable death.[49]

Although some Hong Kong gangster movies are simply vehicles for violent action, the mainstream movies in the genre deal with Triad societies portrayed as quasi-benign organizations.[50] The movie gangster applies the Taoist principles of balance and honor to his conduct. The plots are often similar to those of Hollywood gangster movies, often ending with the fall of the subject of the movie at the hands of another gangster, but such a fall is far less important than a fall from honor.[50] The first movie made by the acclaimed director Wong Kar-wai was a gangster movie, As Tears Go By. In it the protagonist finds himself torn between his desire for a woman and his loyalty to a fellow gangster.[51] Infernal Affairs (2002) is a thriller about a police officer who infiltrates a triad and a triad member who infiltrates the police department. The film was remade by Martin Scorsese as The Departed.[52]

Gangster films make up one of the most profitable segments of the South Korean film industry. Films made in the 1960s were often influenced by Japanese yakuza films, dealing with internal conflict between members of a gang or external conflict with other gangs. The gangsters' code of conduct and loyalty are important elements. Starting in the 1970s, strict censorship caused decline in the number and quality of gangster movies, and none were made in the 1980s.[53] In the late 1980s and early 1990s there was a surge of imports of action movies from Hong Kong. The first of the new wave of important home grown gangster movies was Im Kwon-taek's General's Son (1990). Although this movie followed the earlier tradition, it was followed by a series of sophisticated gangster noirs set in contemporary urban locations, such as A Bittersweet Life (2005).[54]

See alsoGangDacoityOrganized crimeBanditryIllegal drug tradeCategory:Illegal occupationsList of crime bossesList of American mobsters of Irish descentList of Chinese criminal organizationsList of Italian American mobstersList of Jewish American mobstersList of mobsters by cityCitations

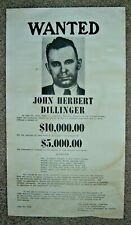

JOHN DILLENGER 1934 "ORIGINAL" BROADSIDE WANTED POSTER $3500.00

1934 ORIGINAL CHEVROLET MOTOR CARS INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE OPERATION $21.87

1934 Original Mickey Mouse Wristwatch Ingersoll Working Disneyana $1100.00

1934 Carreras Oval Film Stars #21 JEAN HARLOW PSA 10 GEM MT $375.25

1934 ORIGINAL BIRTHDAY GREETINGS CARD. MADE IN U.S.A. $12.00

***EXCELLENT*** Vintage 1934 CALIFORNIA License Plates ***ORIGINAL*** PAIR $148.00

JEAN HARLOW w MOTHER ORIGINAL VINTAGE 1934 MGM PORTRAIT DBLWT PHOTO GRIMES C32 $699.99

Microfilm Publication From The US National Archives 1934 WWII Uniforms $94.99

|